See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information may be more similar to your situation.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Music Therapy for Older Adults with Hearing Loss:

Strategies for Increasing Effectiveness of Music and Communication

1, 2

Introduction

This page describes strategies and accommodations to optimize musical and spoken communication when serving older adults with hearing loss.

Presbycusis or age-related hearing loss is a common problem for older adults and is acquired hearing loss (post-lingual) because hearing loss occurs after speech and language skills develop.

Q. Does the age of onset of hearing loss make a difference?

A. Yes. Hearing loss acquired post-lingually as opposed to pre-lingually can result in very different experiences with spoken and musical communication.

-

Mode of communication:

-

Individuals with post-lingual hearing loss have acquired speech and language skills prior to hearing loss. Therefore, they may speak without much difficulty but have greater difficulty hearing what others are saying.

-

Individuals with pre-lingual hearing loss may use other modes of communication, such as sign language or fingerspelling. Manual communication is also associated with severe or profound hearing loss.

-

-

Memory of music:

-

Individuals with post-lingual hearing loss may use their memory of music to compensate for missing sounds. However, the listener may find the sound quality of music disappointing when compared to how music used to sound.

-

Individuals with pre-lingual hearing loss do not have a memory of how music sounded with normal hearing. Consequently, they may have lower expectations of what music “should" or "used to sound like."

-

*This page focuses on older adults with age-related hearing loss.

Q. What communication problems are associated with presbycusis?

A. Communicating with others requires greater focus and concentration because of presbycusis. Difficulty understanding others can put a strain on social interactions. Background music in social settings can make hearing even more difficult (click here for more information). Presbycusis can also reduce music perception and appraisal (enjoyment).

Prolonged concentration in conversations can be exhausting, which can result in miscommunication and affect emotional well-being, including:

-

Increased anxiety in social situations

-

Decreased social interactions, which leads to isolation

-

Depression

-

Decreased self-esteem

Common complaints about music include the following:

-

Difficulty understanding lyrics

-

Volume being too loud/soft

-

Sudden volume changes

-

Difficulty with melody recognition

-

Loss of high frequencies

(Leek, Molls, Kubil, & Tufts, 2008; Rutledge, 2009; Wilhelm, 2020)

Accommodations to Support Music Engagement

Hearing loss can negatively affect the quality of life, create barriers to effective therapeutic interactions, and impact music listening (Wilhelm, 2020). Music therapists can support satisfactory engagement by:

Below are suggestions for enhancing music therapy interventions.

Create a good listening environment:

-

Minimize echoes (i.e., carpets, rugs, drapes). Reverberation makes it harder to understand speech and music.

-

Provide good lighting without glare; don't stand in front of back-lit windows or lamps.

-

This helps people use visual cues (speech reading, facial expressions, gestures) to understand you.

-

-

Move sound sources closer to client.

-

Sit in close proximity.

-

Move sound equipment close to the client.

-

-

Reduce the amount of background noise.

-

When possible, choose a quiet room.

-

Hearing aids will most often pick up on sound in front of the individual, so try and keep the competing noise behind the listener.

-

-

Use a good quality sound system (speakers, microhpnes, etc.)

-

Poor quality sound can be uncomfortable and distort musical sounds.

-

Use hearing devices and assistive listening devices effectively:

-

Confirm whether your client uses a hearing aid or cochlear implant.

-

Check to see if your client's device is working properly.

-

Monitor your client's responses to sound while they are using their device (e.g., responding to your prompts, turning to the sound of an instrument). If you wonder whether the devices are working correctly, you or your client can check to ensure whether they are turne on, and that the battery is in place and properly seated.

-

-

Check the appropriate volume level.

-

-

Use amplification

-

For example, a wireless voice amplifier or microphone

-

Click here for information on assistive listening devices

-

Use clear spoken communication:

-

Clear speech includes the following:

-

Slightly slower speech rate

-

Repeat or rephrase speech as needed

-

Provide context by showing pictures or labels of the discussion topic

-

Pause to emphasize keywords and to allow comprehension

-

-

Gain the listener’s attention prior to speaking

-

Speak face-to-face; keep your mouth clearly visible

-

Maintain close proximity

-

Stay within 3 feet of the listener

-

-

Structure conversation with lower memory requirements (i.e. single instruction, familiar topics)

-

Include non-auditory/visual cues

-

Be mindful to avoid elderspeak

-

Elderspeak is an over accommodation for perceived communicative needs, often based on age-related stereotypes

-

Includes speech that is condescending and patronizing

-

Sounds “sing-song” or “child-like"

-

Includes names that are typically used with young children, like 'sweetie' or 'honey' (though there are cultural differences in the use of these terms)

-

-

Choose and present music to enhance perception and understanding

-

Select music that takes into account the listener's hearing profile (audiogram)

-

Lower sounds are typically easier to hear than higher sounds

-

Audibility of sounds will vary between individuals

-

-

Check with the listener: can they hear the music? does the quality sound good (i.e. undistorted)?

-

Select familiar music

-

Use tactile cues to aid in music perception

-

Pick an instrument with more vibration/stimulation

-

Tap the beat on the listener's hand

-

-

Play music at moderate dynamics

-

Loud music processed through a HA or CI can be painful or distorted

-

Older adults generally prefer lower loudness levels

-

-

Avoid playing music while talking or giving instructions

-

This can mask speech, making it difficult for someone with hearing loss to successfully participate (Gfeller, Darrow, & Wilhelm, 2018)

-

Selecting Musical Instruments

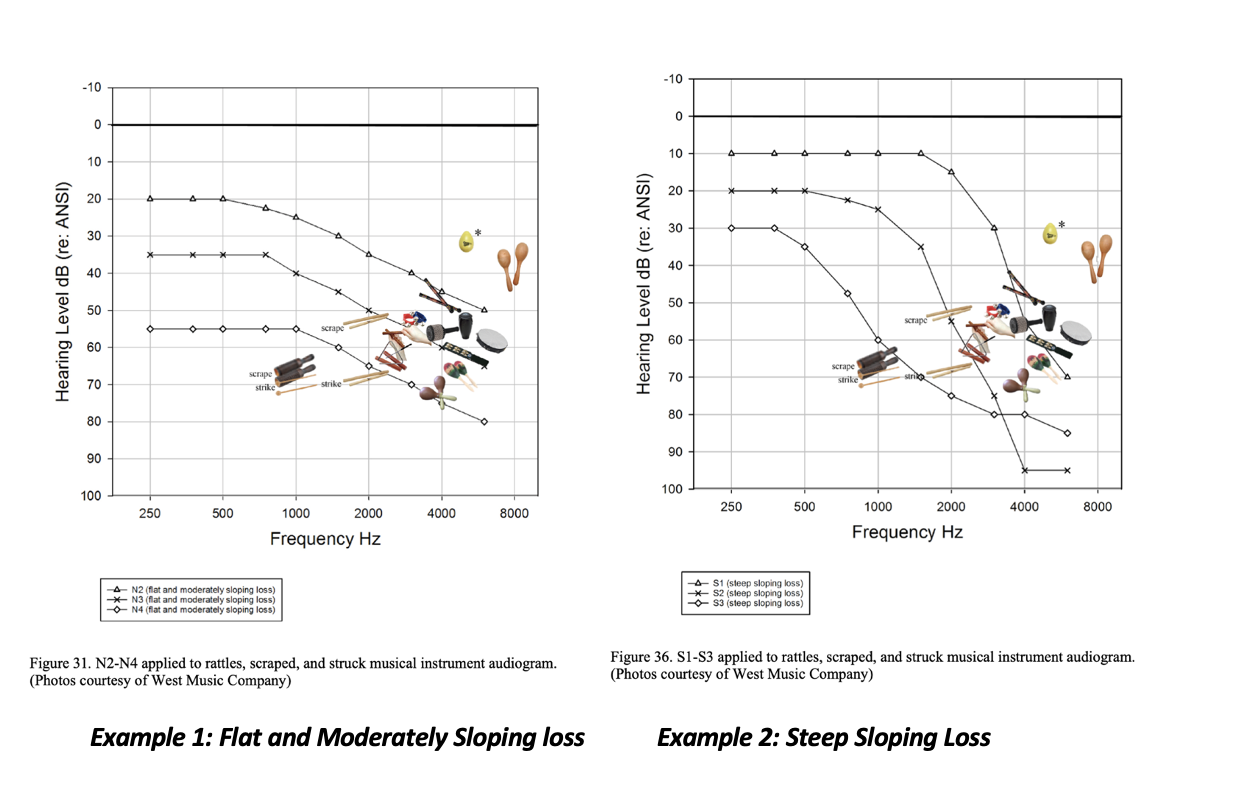

Instrument selection is an important consideration with hearing loss. Research by Lindsey Wilhelm (2016) revealed that some musical instruments are more easily heard by people with hearing loss than others. Audibility of these instruments within common hearing loss profiles (as shown in the audiograms) is shown below.

The figures below show audiograms, which are used by audiologists to describe hearing acuity at different frequencies.

-

The vertical axis indicates loudness (amplitude) and the horizontal axis indicates the frequency (perceived as pitch) of a sound.

-

The small triangles, Xs, and diamond shapes show how loud a sound must be in order to be heard at each frequency.

-

For example, a triangle located at 20 dB at 250 Hz means that the listener can hear pitches around middle C with only 20 dB, which is a very soft sound—about like whispering.

-

-

Each figure below shows three different hearing profiles.

-

The lower the line, the more severe the hearing loss.

-

The more severe the hearing loss, the louder a sound must be played in order to be heard.

-

-

The charts show that a listener may have better hearing for lower pitches rather than higher pitches.

-

The pictures of musical instruments illustrate how high or low their sound is, and how loud it can play.

-

Any musical instrument that is higher than the auditory profile (line with triangles, Xs, or diamonds) will be too soft for that person to hear.

-

NOTE: These audiograms do not demonstrate all possible hearing loss profiles but serve as a starting point for discussion and consideration.

These figures show that some instruments are harder to hear, especially if the person has a more serious hearing loss.

Additional Suggestions and Considerations

-

When fingerpicking on guitar, the top E string may not be audible—avoid emphasizing higher notes.

-

Select lower-pitched instruments when choosing among drums, bass bars, or tone chimes.

-

High-pitched shakers (e.g., egg shakers) or maracas may not be audible—scrape or struck instruments, such as crow sounders or drums, may be better heard.

-

Be cautious about using too many instruments; this can become too loud, and cause some auditory pain.

-

Individuals with hearing loss should have little difficulty with rhythmic elements of music.

-

This is particularly true when combined with tactile or visual input.

-

-

Use trial and error in testing which instruments are most suitable for certain clients.

-

There is a variety of hearing loss profiles and individual differences that impact how music is perceived and enjoyed from person to person.

-

-

Continue to keep in mind individual preferences for musical styles and tone quality.

References

Creech, A., Hallam, S., McQueen, H., & Varvarigou, M. (2013). The power of music in the lives of older adults. Research Studies in Music Education, 35, 87–102. doi:1 0.1177/1321103X13478862

Gfeller, K. E., Darrow, A. A., & Wilhelm, L. A. (2018). Music therapy for persons with sensory loss. In A. Knight, B. LaGasse, and A. Clair (Eds.), Music therapy: An introduction to the profession (pp.217–245). Silver Spring, MD: American Music Therapy Association.

Leek, M. R., Molis, M.R., Kubil, L.R., & Tufts, J.B. (2008). Enjoyment of music by elderly hearing-impaired listeners. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 19(6), 519-526.

Rutledge, K.L. (2009). A music listening questionnaire for hearing aid users (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Canterbury, New Zealand.

Wilhelm, L. A. (2016). Accessibility of music experiences for individuals with age-related hearing loss. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Iowa]. Iowa Research Online.

Wilhelm, L. A. (2020). Strategies for increasing the effectiveness of music therapy with older adults [PowerPoint slides].

Wilhelm, L. A. (2020). Using contextual and visual cues to improve sung word recognition in hearing aid users. Journal of Music Therapy, 57(4), 379–405. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thaa009

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.