return to: Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy

see also: Common Call Problems; Medical Student Resident Page for Otolaryngology

Content compiled by Miles Klimara, MD; Matthew Hoffman, MD, PhD; Deborah Kacmarynski, MD; Jose Manaligod MD

May 5, 2025

POST-TONSILLECTOMY HEMORRHAGE CHECKLIST

|

Emergency Medicine In all cases:

If active bleeding, clot in tonsillar fossa, or non-active bleed with >1 cup EBL:

If not actively bleeding, no clot in tonsillar fossa:

|

Otolaryngology If active bleeding, clot in tonsillar fossa, or non-active bleed with >1 cup EBL:

If hemorrhage recalcitrant to TXA after 20 minutes, recurrent bleeding, clinical concern, or bleeding brisk/uncontrolled:

If not actively bleeding, no clot in tonsillar fossa:

|

|

On discharge

|

|

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

I. Tonsillectomy is one of the most commonly performed procedures by Otolaryngologists, with nearly 300,000 performed annually in the United States (Hall et al. 2017).

II. Tonsillectomy in children is most commonly performed for obstructive sleep apnea and recurrent episodes of tonsillitis. In adults (aged 18 years and older), indications for tonsillectomy can be for a variety of reasons, including the increasing incidence of tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma (Mitchell et al. 2019).

III. Multiple techniques are used to perform tonsillectomy. Intracapsular (subtotal) tonsillectomy preserves the fibrous capsule surrounding the tonsil, and is generally completed with microdebrider or plasma ablation. Extracapsular (total) tonsillectomy removes the entirety of the tonsillar tissue through dissection lateral to the tonsillar capsule, and may be accomplished through a variety of cold steel and cautery techniques.

IV. Intracapsular tonsillectomy is the only tonsillectomy technique which has been shown to result in lower rates of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage (Sedgwick et al. 2023). This should be weighed against the need for revision surgery, particularly in patients with recurrent tonsillitis, as well as the resource utilization associated with intracapsular techniques (Bagwell et al. 2018, Sagheer et al. 2022). There is otherwise no consensus regarding whether specific instrumentation or techniques have the lower rates of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage (Pynonnen et al. 2017, Mitchell et al. 2019).

V. Post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage is a surgical emergency. Bleeding that occurs within the first 24 hours after surgery is referred to as a primary hemorrhage. Secondary hemorrhage occurs after 24 hours, often on post-operative days 5-10, and is generally caused by sloughing of primary eschar as the tonsil bed heals (Mitchell et al. 2019).

VI. All patients and parents of minors should be appropriately counseled pre-operatively about the risk of hemorrhage post-operatively. In meta-analysis of reports of extracapsular (total) tonsillectomy, the risk of primary hemorrhage is 0.1-1%, and secondary hemorrhage is 1.5-4.3% (Francis et al. 2017). Data for intracapsular (subtotal) tonsillectomy are still evolving; single-center studies generally point to a lower risk of hemorrhage than in extracapsular dissection (Attard et al. 2020, Lin et al. 2024).

VII. Many factors have been associated with an increase in the risk of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, including age >5, chronic tonsillitis, and coagulopathies (Wall et al. 2018).

VIII. We routinely screen pediatric patients for increased risk of post-operative hemorrhage with an internal scoring tool developed from the ISTH/SSC Bleeding Assessment Tool (Rodeghiero et al. 2010). For patients with an increased risk of post-operative hemorrhage, evaluation of basic pre-operative laboratory values should be completed. Platelet count, hemoglobin level, and plasma clotting variables should be assessed.

VIII. The presence of coagulation factor deficiencies, von Willebrand disease, and other coagulation/bleeding disorders should prompt preoperative Hematology consultation for pre- operative optimization. Peri- and postoperative antifibrinolytics, desmopressin, and recombinant factors may be considered to optimize factor levels and reduce the risk of high-volume hemorrhage (Patel et al. 2017, Diaz et al. 2021). Children with hemophilia or Von Willebrand Disease exhibit similar rates of primary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage; however, the volume of hemorrhage may be higher and the rate of secondary hemorrhage is approximately 15% (Sun et al. 2013).

IX. Antifibrinolytics (aminocaproic acid, tranexamic) assist in formation of a stable blood clot by preventing fibrinolysis. The role of antifibrinolytics in post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage is rapidly evolving with recent large single-center studies and meta-analyses supporting a decreased need for operative management in patients who receive nebulized or systemic antifibrinolytics (Kuo et al. 2022, Spencer et al. 2022, Shin et al. 2023, Alghamdi et al. 2024). Systemic antifibrinolytics are generally well-tolerated, though co-morbidities/relative contraindications should be considered when evaluating the risk-benefit profile of antifibrinolytic therapy and observation vs. immediate operative intervention. Relative contraindications to common antifibrinolytics include, non-exhaustively, history of significant venous or arterial thrombosis, inherited thrombophilias (Factor V Leiden, antithrombin deficiency), acquired hypercoagulable states (pregnancy-Category B, oral contraceptive use, disseminated intravascular coagulation, advanced malignancy), renal insufficiency, and seizure disorders (Gerstein et al. 2017).

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

A. DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

Patients are often initially encountered in an emergency department setting. Otolaryngology consultation should immediately be sought, IV access obtained, and laboratory evaluation initiated. The patient should be sitting upright, with suction available for active bleeding. Inspection of the oral cavity and oropharynx must be performed, including a thorough inspection of the tonsillar fossa. Physical exam will either reveal no active bleeding, active bleeding, or presence of a clot in the tonsillar fossa. Intravenous access should be obtained early and not delayed until the operating room theater. Patients will often need volume resuscitation. This allows for quick access should the patient's respiratory status acutely decline. Basic labs should be drawn. If there has been a significant decrease in red blood cell volume, consideration should be given regarding a transfusion. Most patients should receive antifibrinolytic treatment (tranexamic acid nebulized and/or IV, aminocaproic acid PO) with the route of administration determined by severity of bleeding and individual patient factors (ability to tolerate nebulized treatments, underlying vascular disease increasing risk profile of systemic therapy).

The degree of bleeding, age, and response to conservative interventions will dictate whether a patient will need to return to the operating room for cauterization. If a patient is not actively bleeding, or there is low volume bleeding, some providers choose close observation for at least several hours, often with the use of systemic and nebulized or topical antifibrinolytics as noted above. If a patient is actively bleeding after initial stabilization measures, or if bleeding recurs after initially being controlled with the use of stabilizing measures and antifibrinolytics, the patient should be taken urgently for control of the hemorrhage. Until the patient is transferred to the operating room, if hemorrhaging is significant, direct pressure, either with a throat pack or gauze, should be applied to the tonsillar fossa if the patient is cooperative.

Control of hemorrhage was historically managed with suture ligation, but suction cautery is more routinely performed today. Suction cautery results in less operating time and a decreased amount of intraoperative blood loss. If bleeding is controlled under local anesthesia, hurricaine spray (benzocaine) may be used for initial anesthetization, followed by viscous lidocaine or a local injection of lidocaine. Local cauterization may be attempted with bipolar cautery or silver nitrate. Post-operatively, oral antifibrinolytics and cessation of ibuprofen should be considered.

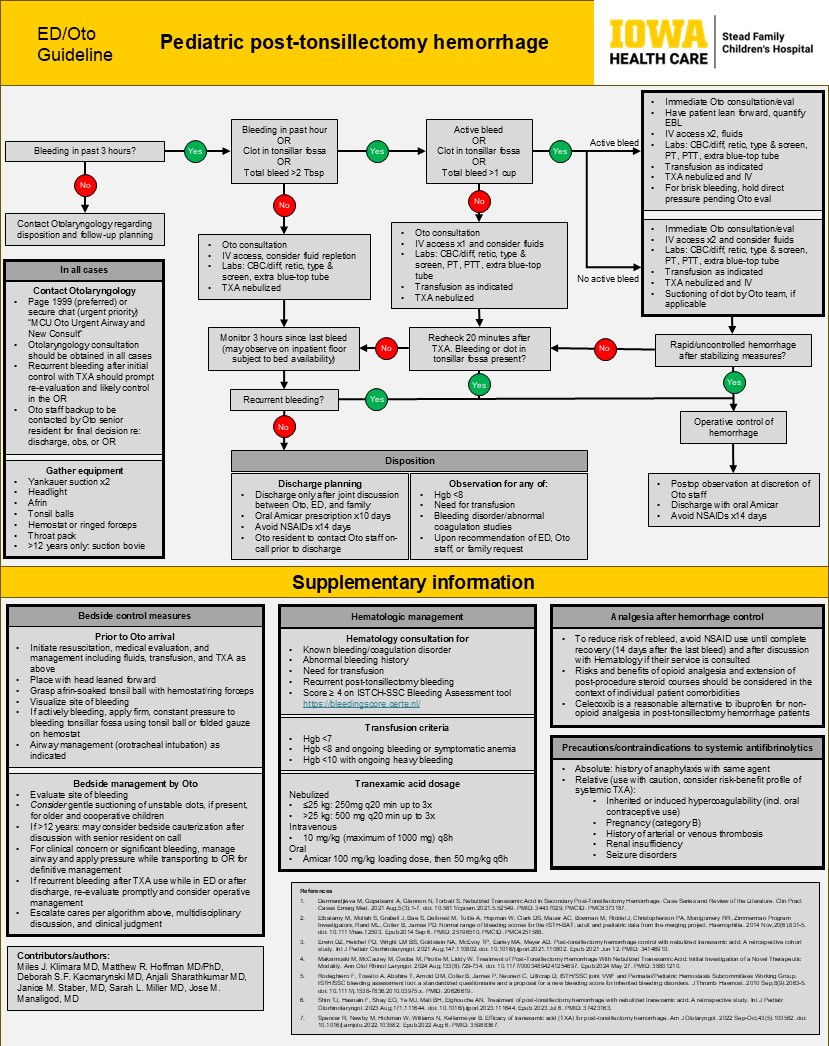

POST-TONSILLECTOMY BLEED MANAGEMENT ALGORITHM:

B. CONSENT (Describe potential complications)

I. Damage to lips, teeth, tongue

II. Further bleeding

III. Dysphagia

IV. Aspiration

V. Death

NURSING CONSIDERATIONS

Tube Placement: The ET (we prefer oral RAE) tube should be placed at exactly midline and brought inferiorly.

A shoulder roll may be used to improve neck extension and optimize the view of operative field.

Special consideration for Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21):

Due to risk of atlanto-axial instability (AAI) in these patients, caution should be used in head positioning, including no shoulder roll and minimal head tilting.

Preoperative x-rays or recent scans should be reviewed prior to the operation date.

Laxity of over 4 mm suggests axial-atlanto instability; due to a low level sensitivity in flexion/extension films in detecting AAI, it is suggested to take neck precautions in all patients with Down Syndrome.

Carefully place the Crowe-Davis retractor, ensuring that tongue blade is appropriate size for access to bilateral tonsillar fossae

This should extend far enough to allow for retraction of the base of tongue but not be too long as to damage the posterior pharyngeal wall.

The tongue may be manipulated into the correct position with the Hurd retractor or blunt Yankauer suction tip

ANESTHESIA CONSIDERATIONS

Patients with a post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, especially children, can have significant associated hazards. Patients with a post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage may have associated anemia, hypovolemia, and sequestered blood in the stomach, which leads to a theoretical increase risk in aspiration (Fields et al. 2010). In the emergent setting, rapid sequence intubation (RSI) is often performed. RSI includes cricoid pressure, an induction agent, neuromuscular blocking agent, but no mask ventilation, followed by a quick intubation by anesthesiology (Stollings et al. 2014).

OPERATIVE PROCEDURE (example)

After written informed consent was obtained, the patient was brought back to the operating room by Anesthesiology and placed supine on the operating room table. A pre-induction checklist was performed. An IV was placed, and the patient was mask ventilated. Rapid sequence intubation was performed, and the patient was orotracheally intubated without difficulty. The bed was turned 90 degrees from Anesthesiology. A Crowe-Davis retractor was placed with good visualization of the oropharynx. Eschar was noted in the left inferior tonsil bed, partially dislodged, but with no bleeding. After a small amount of clot was removed, left inferior pole slow oozing began and was controlled with bipolar cautery set at 20. The right tonsil fossa was examined with no evidence of blood or clot. Valsalva to 30 was performed with no bleeding. The stomach was suctioned multiple times. The patient was then taken out of suspension and the Crowe-Davis was removed. The patient's mouth was wiped clean and then turned back to Anesthesiology in stable condition. The patient was then extubated uneventfully.

REFERENCES

Hall MJ, Schwartzman A, Zhang J, Liu X. Ambulatory Surgery Data From Hospitals and Ambulatory Surgery Centers: United States, 2010. Natl Health Stat Report. 2017 Feb;(102):1-15. PMID: 28256998.

Mitchell RB, Archer SM, Ishman SL, Rosenfeld RM, Coles S, Finestone SA, Friedman NR, Giordano T, Hildrew DM, Kim TW, Lloyd RM, Parikh SR, Shulman ST, Walner DL, Walsh SA, Nnacheta LC. Clinical Practice Guideline: Tonsillectomy in Children (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Feb;160(1_suppl):S1-S42. doi: 10.1177/0194599818801757. PMID: 30798778.

Sedgwick MJ, Saunders C, Bateman N. Intracapsular Tonsillectomy Using Plasma Ablation Versus Total Tonsillectomy: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. OTO Open. 2023 Feb 17;7(1):e22. doi: 10.1002/oto2.22. PMID: 36998549; PMCID: PMC10046729.

Bagwell K, Wu X, Baum ED, Malhotra A. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Intracapsular Tonsillectomy and Total Tonsillectomy for Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2018 Aug;16(4):527-535. doi: 10.1007/s40258-018-0396-4. PMID: 29797301.

Sagheer SH, Kolb CM, Crippen MM, Tawfik A, Vandjelovic ND, Nardone HC, Schmidt RJ. Predictive Pediatric Characteristics for Revision Tonsillectomy After Intracapsular Tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022 Apr;166(4):772-778. doi: 10.1177/01945998211034454. Epub 2021 Aug 10. PMID: 34372707.

Pynnonen M, Brinkmeier JV, Thorne MC, Chong LY, Burton MJ. Coblation versus other surgical techniques for tonsillectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Aug 22;8(8):CD004619. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004619.pub3. PMID: 28828761; PMCID: PMC6483696.

Francis DO, Fonnesbeck C, Sathe N, McPheeters M, Krishnaswami S, Chinnadurai S. Postoperative Bleeding and Associated Utilization following Tonsillectomy in Children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Mar;156(3):442-455. doi: 10.1177/0194599816683915. Epub 2017 Jan 17. PMID: 28094660; PMCID: PMC5639328.

Attard S, Carney AS. Paediatric patient bleeding and pain outcomes following subtotal (tonsillotomy) and total tonsillectomy: a 10-year consecutive, single surgeon series. ANZ J Surg. 2020 Dec;90(12):2532-2536. doi: 10.1111/ans.16306. Epub 2020 Sep 23. PMID: 32964591.

Lin H, Hajarizadeh B, Wood AJ, Selvarajah K, Ahmadi O. Postoperative Outcomes of Intracapsular Tonsillectomy With Coblation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024 Feb;170(2):347-358. doi: 10.1002/ohn.573. Epub 2023 Nov 8. PMID: 37937711.

Wall JJ, Tay KY. Postoperative Tonsillectomy Hemorrhage. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2018 May;36(2):415-426. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2017.12.009. Epub 2018 Feb 10. PMID: 29622331.

Rodeghiero F, Tosetto A, Abshire T, Arnold DM, Coller B, James P, Neunert C, Lillicrap D; ISTH/SSC joint VWF and Perinatal/Pediatric Hemostasis Subcommittees Working Group. ISTH/SSC bleeding assessment tool: a standardized questionnaire and a proposal for a new bleeding score for inherited bleeding disorders. J Thromb Haemost. 2010 Sep;8(9):2063-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03975.x. PMID: 20626619.

Patel PN, Arambula AM, Wheeler AP, Penn EB. Post-tonsillectomy hemorrhagic outcomes in children with bleeding disorders at a single institution. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Sep;100:216-222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.014. Epub 2017 Jul 14. PMID: 28802375.

Diaz R, Musso M, Mahoney D. Effective hemostasis in children with Von Willebrand factor defects undergoing adenotonsillar procedures. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021 Feb;38(1):25-35. doi: 10.1080/08880018.2020.1806970. Epub 2020 Aug 17. PMID: 32804010.

Sun GH, Auger KA, Aliu O, Patrick SW, DeMonner S, Davis MM. Posttonsillectomy hemorrhage in children with von Willebrand disease or hemophilia. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013 Mar;139(3):245-9. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.1821. PMID: 23657425.

Spencer R, Newby M, Hickman W, Williams N, Kellermeyer B. Efficacy of tranexamic acid (TXA) for post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022 Sep-Oct;43(5):103582. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103582. Epub 2022 Aug 6. PMID: 35988367.

Kuo CC, DeGiovanni JC, Carr MM. The efficacy of Tranexamic Acid Administration in Patients Undergoing Tonsillectomy: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2022 Aug;131(8):834-843. doi: 10.1177/00034894211045264. Epub 2021 Sep 13. PMID: 34515540.

Shin TJ, Hasnain F, Shay EO, Ye MJ, Matt BH, Elghouche AN. Treatment of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage with nebulized tranexamic acid: A retrospective study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2023 Aug;171:111644. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2023.111644. Epub 2023 Jul 6. PMID: 37423163.

Alghamdi AS, Hazzazi GS, Shaheen MH, Bosaeed KM, Kutubkhana RH, Alharbi RA, Abu-Zaid A, Felemban RA. Nebulized tranexamic acid for treatment of post-tonsillectomy bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024 Oct 2. doi: 10.1007/s00405-024-08995-1. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39356357.

Gerstein NS, Brierley JK, Windsor J, Panikkath PV, Ram H, Gelfenbeyn KM, Jinkins LJ, Nguyen LC, Gerstein WH. Antifibrinolytic Agents in Cardiac and Noncardiac Surgery: A Comprehensive Overview and Update. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017 Dec;31(6):2183-2205. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.02.029. Epub 2017 Feb 5. PMID: 28457777.

Fields RG, Gencorelli FJ, Litman RS. Anesthetic management of the pediatric bleeding tonsil. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20(11):982-986. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03426.x

Stollings JL, Diedrich DA, Oyen LJ, Brown DR. Rapid-sequence intubation: a review of the process and considerations when choosing medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(1):62-76. doi:10.1177/1060028013510488