see also: Esophageal Reflux Precautions

TERMINOLOGY

- The term "globus" has been used a general term to describe the symptom of "throat fullness" or "lump in the throat"

- Others have more specifically identified globus as a "functional" syndrome without an organic association termed "globus syndrome", "globus pharyngeus", "globus sensation" per Rome criteria (see below: EVALUATION- Rome IV Diagnostic Criteria for Globus Syndrome)

- Definition: Globus Syndrome-A functional esophageal disorder characterized by an intermittent or constant, non-painful sensation of fullness or lump/foreign body in the throat ("globus" is Latin for "ball"). Globus syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion that requires the absence of structural, histopathological (mucosal), or esophageal motility abnormalities. This functional disorder not associated with dysphagia, odynophagia or reflux, though the globus sensation itself may co-occur with these symptoms. Symptoms may improve with eating or swallowing (Aziz et al. 2016).

HISTORY

- ~486 BCE: Hippocrates first described globus sensation (lump in throat), believed to be limited to women due to the proposed link between hysteria and uterine dysfunction. The term "globus" is Latin for "ball" (Harrar et al 2004)

- 1707: John Purcell coins the term "globus hystericus" as he attributed globus to "hysteric fits". He described globus as a result of increased pressure on the thyroid cartilage due to contraction of neck strap muscles.

- 1968: K.G. Malcomson coins the more accurate term "globus pharyngeus" as he showed most patients with globus did not have a hysterical personality nor mostly female. He is also responsible for elucidating gastroesophageal reflux as a possible etiology for globus. (Cashman et al. 2010)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

- Prevalence: Ranges from 3.5% to 46% depending on the population and diagnostic criteria

- 3.5% prevalence of globus syndrome (Cross-sectional study of 995 young, healthy Iranians assessed using the Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional GI disorders- Adibi et al 2012) (see below EVALUATION: Rome IV Diagnostic Criteria for Globus Syndrome)

- 6.0% prevalence of globus feeling for >3 months (Survey of 1,158 women from general population in United Kingdom, not using Rome III criteria- Dreary et al 1995)

- 21.5% overall lifetime prevalence of globus syndrome (Survey of >3,000 participants in China using Rome III criteria- Tang et al. 2016)

- 46% have at one point in their life "felt like a lump is in their throat" (Interview of 147 healthy individuals in United Kingdom, not using Rome III criteria- Thompson et al. 1982)

- In Primary Care:

- Globus is managed in 6.7 per 100,000 encounters in primary care (Pollack et al 2013)

- In ENT Practice:

- 4-5% of all ENT outpatient referrals are due to globus sensation (Moloy et al. 1982).

- Sex:

- Women may be affected more often (reported in some studies in a 2:1 ratio compared to males), however some studies find no difference in incidence between sexes (Selleslagh et al. 2013)

- Age:

- Middle-aged (35-54 years old) may be commonly affected, but some studies found no association of globus prevalence with age (Tang et al 2016).

- Region

- May be more likely in urban populations due to increased environmental stressors (Tang et al 2016).

ANATOMY

- Commonly found midline between the thyroid cartilage and sternal notch (Aziz et al. 2016).

- Suspicion for organic cause of globus sensation should be higher if not found in common anatomical region, such as unilaterality (Timon et al. 1991).

ETIOLOGIES (PATHOGENESIS)

- Pharyngeal and upper esophageal sphincter dysfunction (Selleslagh et al. 2013)

- Hypotheses:

- Elevated resting pressure of the upper esophgeal sphincter (UES) leads to globus sensation

- During swallowing, delayed UES opening , incomplete UES relaxation, early UES closure or cricopharyngeal spasms may contribute to globus sensation

- Elevated UES resting pressure may be a factor in as many as 68% of patients with globus sensation, though some studies have not been able to show an association of UES pressure to globus. Stress, respiration and distal esophageal acid exposure may all contribute to elevated UES pressure.

- Results of UES resting pressure in globus studies remain inconclusive due the small sample sizes and varying measurement techniques.

- Hypotheses:

- Psychological abnormalities (Selleslagh et al. 2013)

- Hypothesis:

- Affective symptoms such as anxiety, depression and stress can alter sensory perceptions leading to somatization with symptoms of globus sensation. Conversely, chronic globus sensation may cause increased anxiety, depression and stress.

- Associations of globus with affective symptoms have largely been determined by numerous cross-sectional studies using validated scales.

- 96% of patients with globus symptoms report exacerbations during periods of "high emotional intensity" (Lee et al. 2012)

- In a prospective cohort of 36 globus patients, a negative diagnostic workup for malignancy led to a reduction in anxiety levels. This reduction was the strongest predictor for globus symptom improvement (Oishi et al. 2013)

- Women have a higher incidence of affective disorders and may be more likely to present with globus secondary to an underlying affective symptomatology (Robson et al. 2019).

- Prior to more recent studies, including Deary et al. 1995, it was believed that globus was due to a hysterical personality traits (hence the term "globus hystericus"). Modern evidence of hysterical personality traits in the pathogenesis of globus is limited.

- Hypothesis:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) (Selleslagh et al. 2013)

- Hypotheses:

- An extraesophageal manifestation of GERD. Distal acidic esophageal reflux reaching the upper esophagus and UES leads to increased UES tone, giving globus sensation.

- Globus may be attributed to reflux going past esophagus into hypopharynx causing irritation and inflammation to laryngeal tissue (laryngopharyngeal reflux).

- Non-acidic reflux causes esophageal distention that contributes to globus sensation, especially those with visceral hypersensitivity

- Prevalence of globus sensation in reflux (15-28%) appears to be higher than patients without reflux (4-10%) (Selleslagh et al. 2013).

- Disconcordance in studies linking esophageal pH to globus symptoms in patients with reflux. Conflicting evidence whether there is a difference in pH in controls vs. globus patients with reflux.

- Many patients with reflux and globus may have non-acidic reflux, suggesting the role esophageal distention in globus, independent of acid (Tokashiki et al. 2010).

- Hypotheses:

- Visceral hypersensitivity

- Hypothesis: increased visceral sensitivity of esophagus/upper esophageal sphincter leads to the sensation of a lump in the throat (globus).

- Visceral hypersensitivity: Describes pain or discomfort in visceral organs (such as GI tract) that is more intense than normal or requires a lower threshold for stimulation.

- 7/9 globus patients (vs. 0/11 controls) had lower perception and pain thresholds during balloon dilation of the esophagus, but no difference with electrical stimulation of esophagus (Chen et al. 2009). Globus patients showed increased sensitization (progressive lowering of pain threshold) to balloon distention in a similar study with 42 globus patients (Rommel et al. 2012).

- Multifactorial

- Most likely to be some combination of all these factors. In general, finding a specific etiology for globus syndrome remains a challenge. (Selleslagh et al. 2013)

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GLOBUS SYMPTOMS

- Globus Syndrome (defined as a functional gastrointestinal disorder, see * below) (Aziz 2016)

- Visceral hypersensitivity (Chen 2009, Rommel 2012)

- Psychological abnormalities (Selleslagh et al. 2013)

- Esophageal motility disorders (61% of globus symptoms with organic abnormalities- Moser et al. 1998)

- Achalasia (27%)

- Mechanical obstruction (e.g, strictures, esophageal carcinoma, postcricoid webs, paraesophageal masses, goiter, vallecular cyst)

- Diffuse esophageal spasms (DES) (1%)

- Nutcracker/jackhammer esophagus (hypercontractile esophagus) (3%)

- Absent peristalsis (e.g., scleroderma, radiation)

- GERD (14%) or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR)

- Pharyngeal inflammation (pharyngitis, tonsillitis, and chronic sinusitis) (7%)

- Hiatal hernia (2.6-15.3% -Harar et al. 2004, Alaani et al. 2007, Hajioff et al. 2004)

- Upper esophagus disorders

- Esophageal inlet patch (heterotopic gastric mucosa at UES)

- Hypertensive upper esophageal sphincter

- Zenker's diverticulum

- Mass (tumor) in the tongue base including thyroglossal duct cyst (Li 2019)

- Iatrogenic (head and neck surgery- uvulopalatopharyngoplasty)

- Eosinophilic/pill esophagitis

EVALUATION

- Rome IV Diagnostic Criteria for Globus Syndrome (a functional gastrointestinal disorder)*

- All criteria must be present for the past 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis of globus. Must have symptoms at least once per week.

- Persistent or intermittent, nonpainful, sensation of a lump or foreign body in the throat with no structural lesion identified on physical examination, laryngoscopy, or endoscopy.

- Occurrence of the sensation between meals.

- Absence of dysphagia or odynophagia.

- Absence of a gastric inlet patch in the proximal esophagus.

- Absence of evidence that gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis is the cause of the symptom.

- Absence of major esophageal motor disorders (achalasia/ esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction, diffuse esophageal spasm, jackhammer esophagus, absent peristalsis)

- Persistent or intermittent, nonpainful, sensation of a lump or foreign body in the throat with no structural lesion identified on physical examination, laryngoscopy, or endoscopy.

- *Rome IV criteria are sets of diagnostic criteria for determining functional gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, nausea/vomiting syndromes, globus, functional heartburn, etc.) set by the Rome Foundation

- The Rome Foundation is an independent not-for-profit organization that provides support for activities designed to create scientific data and educational information to assist in the diagnosis and treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). The first committee meetings over FGIDs criteria convened in Rome, Italy in 1988 and thus named The Rome Foundation.

- All criteria must be present for the past 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis of globus. Must have symptoms at least once per week.

- History

- Primary complaint: Sensation of "lump in throat","throat fullness", "food stuck in throat", "throat tightness", "scratchy throat"

- May improve with swallowing or eating (with solids and liquids vs. dry swallow)

- May worsen with strong emotional states, stress, anxiety, nervousness, dry swallowing

- Intermittent symptoms (70%) or constant (30%) (Robson et al. 2019)

- Onset: More often sudden/acute (56%), can be gradual/progressive (Timon et al. 1991)

- Duration: Days to years (average of 6 months, range 3 days to 30 years- Tang et al. 2016)

- Globus sensation is the only symptom in 50% of patients (Harar et al. 2004)

- Concomitant symptoms seen with primary complaint of globus sensation (50% of patients):

- Throat clearing, dryness, soreness (most common- Rowley et al. 1995)

- Heartburn (20% of anyone with globus complaint- Harar et al. 2016)

- Reflux (16%)- Can use Reflux Symptom Index to determine severity

- Dysphagia (14%)

- Throat pain (12%)

- Aspiration/choking (8%)

- Chronic cough

- Screen for alarm symptoms/signs (suggestive of underlying organic cause or malignancy)

- Dysphagia (especially progressive)

- Odynophagia

- Aspiration

- Regurgitation

- Weight loss

- Voice changes/hoarseness

- Pain

- Lateralization of symptoms

- Tonsillar/neck mass

- Cervical adenopathy

- Risk factors for aerodigestive malignancy: smoking, alcohol use, HPV status, GERD, age, family history

- Primary complaint: Sensation of "lump in throat","throat fullness", "food stuck in throat", "throat tightness", "scratchy throat"

- Physical Exam

- Complete exam of neck and oropharynx

- Inspection for neck/oral masses, adenopathy, tonsillar/pharyngeal inflammation, mucosal dryness and pallor

- Palpation lymph nodes, parotid/salivary glands, thyroid with and without swallowing, trachea, oral cavity

- Complete exam of neck and oropharynx

- Refer to ENT

- If positive for alarm symptoms or symptoms consistent with globus syndrome from H&P.

- ENT Workup Options

- Transnasal fiberoptic laryngoscopy (FOL) or transnasal flexible laryngoesophagoscopy (TNO)

- Purpose: Rule out structural lesions. FOL- provides visualization of oropharynx and larynx. TNO- provides visualization of oropharynx, larynx and proximal esophagus. (video of transnasal laryngoscopy)

- Recommended in every patient for globus workup (Kortequee et al. 2013)

- 13% (91/699) of patients with globus symptoms showed abnormalities (Harar et al. 2004)

- Posterior laryngitis (7.2%- half of all abnormalities found)

- <1% of all patients: vocal fold nodules, saliva pooling, vocal cord paralysis, vocal cord polyp, vallecular cyst, Reinke's edema, piriform fossa lesions.

- **In the presence of isolated globus sensation with an otherwise normal history, physical exam and FOL/TNO, further investigation has low diagnostic yield***

- Barium swallow study

- Purpose: Exclude upper aerodigestive tract malignancies. Also known as an esophagram- provides visualization of entire esophagus during swallowing.

- Poor sensitivity (50%) for detecting small pharyngeal/esophageal carcinomas (Alaani et al. 2007)

- 61-75% of patients with globus symptoms showed no abnormalities (Harar et al. 2004, Alaani et al. 2007, Hajioff et al. 2004)

- 25-39% of patients had abnormalities, all benign

- Cervical osteophytes (0.3-33%)

- Gastroesophageal reflux (2.2-18.5%)

- Cricopharyngeus spasm (3.9-16%)

- Hiatal hernia (2.6-15.3%)

- Pharyngeal pouch (2.3-3.6%)

- Suspected tumors (1%- benign on all biopsies in Alaani et al. 2007)

- Purpose: Exclude upper aerodigestive tract malignancies. Also known as an esophagram- provides visualization of entire esophagus during swallowing.

- Modified barium swallow study

- Purpose: Detect and assess any oropharyngeal dysfunction such as aspiration. Also known as videofluoroscopy- provides visualization of oropharynx during swallowing.

- Utility not well studied

- Abnormal in 35% (8/23): Most common abnormalities were laryngeal aspiration, barium stasis in vallecula/pyriform sinus, poor pharyngeal elevation (Lee et al. 2012)

- Upper endoscopy

- Purpose: Detect and assess for reflux esophagitis, esophageal malignancies, eosinophilic esophagitis and gastric inlet patch (Robson et al. 2019)

- Poor sensitivity for diagnosis of extra-esophageal GERD (e.g, In laryngopharyngeal reflux, only 19% had evidence of esophagitis/Barrett's metaplasia) (Lee et al. 2012).

- 27% (30/112) of patients with globus symptoms showed abnormalities (Harar et al. 2004)

- Common findings on flexible endoscopy: reflux esophagitis (47%), hiatal hernia (49%) (Lorenz et al. 1993)

- **Perform if alarm symptoms present**

- Purpose: Detect and assess for reflux esophagitis, esophageal malignancies, eosinophilic esophagitis and gastric inlet patch (Robson et al. 2019)

- Esophageal manometry

- Purpose: Detect esophageal motility disorders by assessing the amplitude and timing of upper and lower esophageal sphincter pressures with esophageal body peristalsis and amplitudes. Important for ruling out achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasms, nutcracker esophagus, absent peristalsis (scleroderma, radiation).

- Most useful if concomitant dysphagia with negative upper endoscopy and unsuccessful PPI trial (Selleslagh et al. 2013)

- Mixed evidence whether UES dysfunction (incomplete UES relaxation, delayed opening/closing) is associated with globus syndrome (Selleslagh et al. 2013)

- Globus may show hyperdynamic changes of UES during respiration. (Kwiatek et al. 2009)

- 60% of patients with globus symptoms (and/or concomitant symptoms such as dysphagia and reflux) had >27 mmHg fluctuations of UES with respiration. These fluctuations were significantly higher compared to patients with no globus symptoms.

- Esophageal pH and impedance

- Purpose: Determine if reflux symptoms are associated with changes in esophageal pH. Useful in ruling out GERD or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR)

- Most useful if patient has globus with typical gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and fails empirical PPI trial

- Up to 45% of patients with gastroesophageal reflux continue to have reflux symptoms despite high dose PPI use, suggesting pH monitoring would be helpful in determining the etiology of reflux in many patients (El‐Serag et al. 2010).

- Purpose: Determine if reflux symptoms are associated with changes in esophageal pH. Useful in ruling out GERD or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR)

- Thyroid Ultrasound

- Purpose: assessment of thyroid in patients with goiter or nodules on exam or symptoms/signs suggestive of hyper/hypothyroidism. Not routine for workup of globus.

- Neck CT/MRI

- Purpose: Assessment of head and neck malignancies/masses if masses or adenopathy is noted on exam. Not routine for workup of globus.

- Transnasal fiberoptic laryngoscopy (FOL) or transnasal flexible laryngoesophagoscopy (TNO)

MANAGEMENT

- Currently, there is no consensus for the appropriate evaluation/management of globus syndrome. There is no single effective treatment for globus syndrome.

- Webb et al. 2000: Postal questionnaire survey of 307 United Kingdom ENT consultants given a scenario of a 30 -year-old woman with globus symptoms for the last 4 months with unremarkable physical exam and laryngoscopy.

- 10% would give reassurance only

- 4% would give reassurance and antireflux medication only (52% of all consultants prescribed antireflux medication)

- 61% ordered rigid endoscopy

- 56% ordered barium swallow

- 17.5% ordered both rigid endoscopy and barium swallow (regardless of the results of either)

- 0% ordered pH monitoring

- 12% referred to speech therapy

- <1% referred to either physiotherapy or psychiatry

- Webb et al. 2000: Postal questionnaire survey of 307 United Kingdom ENT consultants given a scenario of a 30 -year-old woman with globus symptoms for the last 4 months with unremarkable physical exam and laryngoscopy.

- Current Management Options

- Treat underlying organic pathology if present

- Reassurance: globus syndrome is a benign condition

- Given the benign nature and lack of a single effective treatment, reassurance is the mainstay of globus syndrome treatment.

- Diagnostic rule out of malignancy with reassurance may reduce anxiety levels and concomitant globus symptoms (Oishi et al. 2013)

- Most cost-effective treatment.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Empirical high-dose PPI (omeprazole 20mg twice daily for 6-8 weeks)- (Robson et al. 2019)

- Mixed evidence on the efficacy of PPIs for globus symptom improvement

- 52% of ENT consultants initiate empirical antireflux treatment in patients presenting with globus (Webb et al. 2000)

- Jeon et al. 2013 demonstrated in 41 patients with globus, 54% (22/41) had >50% improvement in globus symptoms after a 4 week trial of pantoprazole 40mg daily (responders). Clinical indicators of response were concomitant:

- GERD symptoms (reflux, regurgitation, heartburn)

- <3 months duration of globus symptoms

- Lower initial globus symptom severity

- A systematic review of PPI use in patients with suspected laryngopharyngeal reflux (including those with globus) failed to show superiority of PPIs over placebo in the laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms (Karkos et al. 2009)

- Speech Therapy

- Includes behavioral modifications such as reduced throat clearing, adequate hydration, stress management techniques, manipulation/massaging of larynx, "yawn-sigh" technique (mimic yawning/sighing), "giggle posture" (mimic movement of larynx during laughing).

- Wareing et al. 2009 showed improvement in globus symptoms in 92% (23/25) of patients undergoing speech therapy.

- In 98 patients with globus pharyngeus who completed 3 months of speech therapy, globus symptom severity decreased from 6.6/10 pre-intervention to 2.6/10 post-intervention. This was found to be more effective than reassurance alone (Khalil et al. 2011).

- Antidepressants/Psychiatric Consultation

- Limited evidence overall for improvement of globus symptoms with antidepressants. May be helpful if etiology is visceral hypersensitivity.

- 30 patients with globus pharyngeus were randomly divided into treatment for 4 weeks with low-dose 25mg amitriptyline once daily and 40 mg pantoprazole once daily vs. 40mg pantoprazole once daily alone (control) (You et al. 2013)

- 75% (12/16) taking amitriptyline and pantoprazole had significant improvement in globus symptoms vs. 36% (5/14) in control group.

- Low-dose amitriptyline is a safe option for treatment of globus

- Case reports have indicated that treatment of underlying psychiatric disorder may improve globus symptoms (Weijenborg et al. 2015)

- Gabapentin

- Limited evidence overall. May be helpful if etiology is visceral hypersensitivity.

- A retrospective study of 87 patients with globus symptoms that received PPI, gabapentin (300mg, 3x/week for at least 2 weeks) or both (Kirch et al. 2013):

- 57% (8/14) patients on gabapentin who previously failed PPI therapy had improvement or resolution of globus symptoms

- 68% (21/31) of all patients taking gabapentin had improvement or resolution of globus symptoms

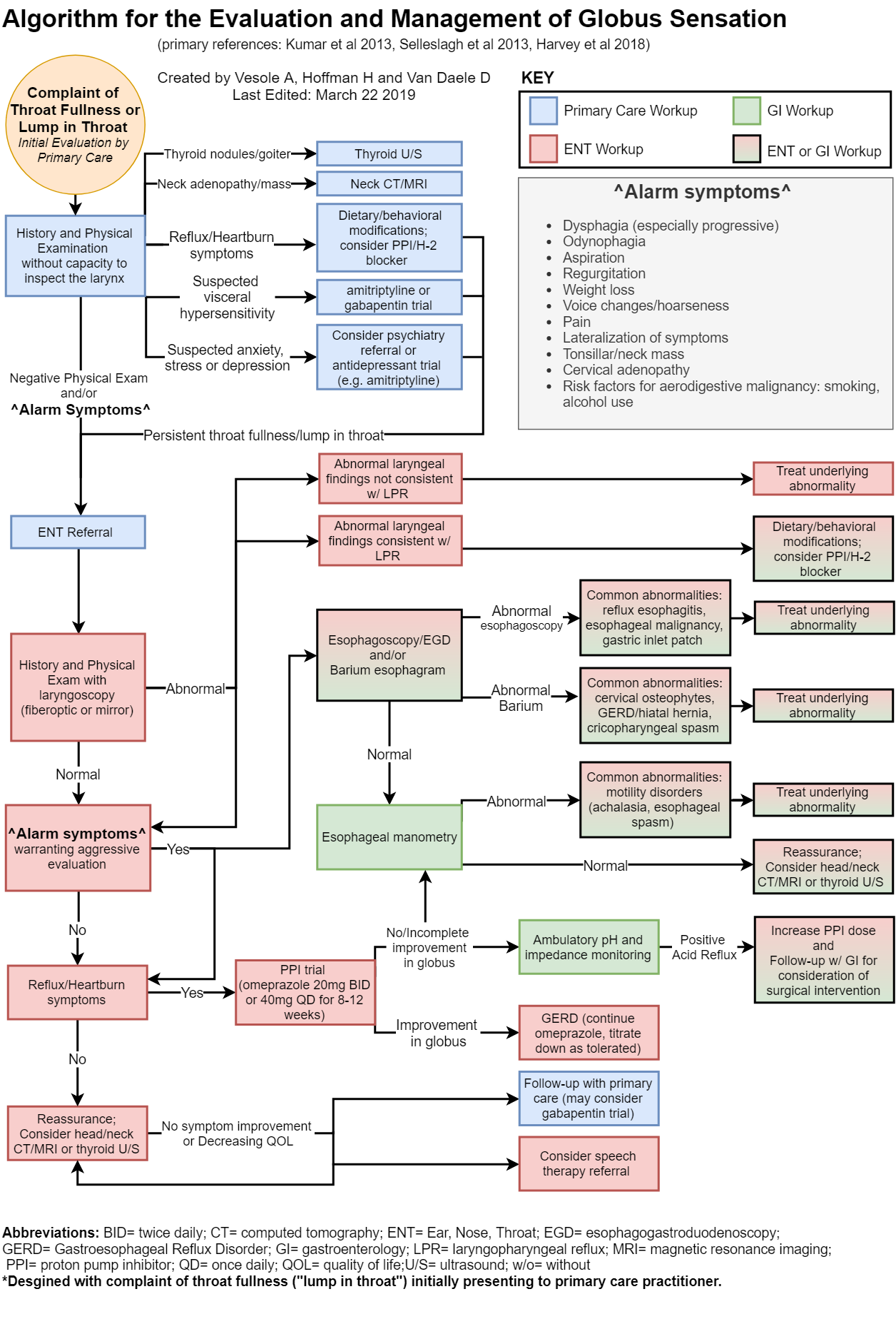

Proposed algorithm for evaluation and management of globus:

Globus Workup Checklist |

|

|---|---|

Primary Care |

ENT/GI |

|

History and Physical without capacity to inspect the larynx |

History and Physical with laryngoscopy |

|

If reflux/heartburn: PPI Trial/H-2 trial and Esophageal Reflux Precautions |

If reflux/heartburn: PPI Trial/H-2 Trial and Esophageal Reflux Precautions |

|

If suspected anxiety, stress, depression: Psychiatry referral and/or management by primary care with medical management |

If suspected anxiety, stress, depression: Psychiatry and/or primary care referral |

|

If suspected visceral hypersensitivity: Trial of gabapentin or amitriptyline |

If suspected visceral hypersensitivity: Trial of gabapentin or amitriptyline |

|

If concern for thyroid nodules/goiter: Thyroid Ultrasound |

If concern for thyroid nodules/goiter: Thyroid Ultrasound |

|

If concern for head/neck adenopathy/mass: Head/Neck CT/MRI |

If concern for head/neck adenopathy/mass: Head/Neck CT/MRI |

|

If persistent symptoms after PPI/psych workup: ENT referral |

If failed PPI trial: Consider pH and impedance monitoring and/or GI follow-up (may consider more aggressive treatment possible surgery) |

|

If negative physical exam and/or positive for alarm symptoms: ENT referral Alarm symptoms:

|

If alarm symptoms:

|

|

Referral to speech therapy |

Referral to speech therapy |

|

If all above workup is negative/unsuccessful: Reassurance with close primary care follow-up (may consider gabapentin/amitriptyline trial) |

If all above workup is negative/unsuccessful: Reassurance with close primary care follow-up |

PROGNOSIS

- Globus Syndrome: Benign condition with no organic origin (by definition)

- No study to date has demonstrated any development of aerodigestive tract malignancy associated with isolated globus pharyngeus in patients (Cashman et al. 2010)

- Timon et al. 1991-A prospective study of 80 patients diagnosed with globus pharyngeus:

- Average follow-up of 27 months (range 21-42 months) with treatment (cimetidine and antacid) if co-occurring reflux symptoms were present. This treatment did not significantly alter globus symptom outcomes)

- 25% symptom-free, 75% had persistent symptoms, 35% had persistent yet significantly improved symptoms

- Favorable prognostic factors: male sex, symptom onset < 3 months, absence of other throat symptoms (e.g., dryness, constant throat clearing)

- Rowley et al. 1995- A prospective study of 67 patients diagnosed with globus pharyngeus (continuation of Timon et al. 1991 cohort):

- Average follow-up of 7.6 years (range 7.0-8.8 years)

- 55% symptom-free, 45% had persistent symptoms, 25% had persistent yet significantly improved symptoms

- No significant prognostic indicators at longer follow-up interval

- Cashman et al. 2010- A retrospective study of 55 patients diagnosed with globus symptoms > 6 months with normal rigid endoscopies and barium swallows:

- Average follow-up of 5.3 years (range 3.0-7.7 years)

- 56% "symptomatic improvement", 44% persistent symptoms

- Summary:

- Globus syndrome is benign condition with no organic pathologies by definition

- The majority will have improvement or resolution of globus symptoms over the course of years with reassurance and/or anti-reflux medication.

- A large number will still have no long-term improvement in globus symptoms, however they are not likely to worsen. Globus is difficult to treat in this patient population.

RECOMMENDED READING

Robson KM, Lembo AJ.Globus sensation. Grover S, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc. https://www.uptodate.com(Accessed on February 25, 2019)

Lee, B. E., & Kim, G. H. (2012). Globus pharyngeus: a review of its etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG, 18(20), 2462.

REFERENCES

Adibi, P., Behzad, E., Shafieeyan, M., & Toghiani, A. (2012). Upper functional gastrointestinal disorders in young adults. Medical Archives, 66(2), 89.

Alaani, A., Vengala, S., & Johnston, M. N. (2007). The role of barium swallow in the management of the globus pharyngeus. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology, 264(9), 1095-1097.

Aziz, Q., Fass, R., Gyawali, C. P., Miwa, H., Pandolfino, J. E., & Zerbib, F. (2016). Esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1368-1379.

Cashman, E. C., & Donnelly, M. J. (2010). The natural history of globus pharyngeus. International journal of otolaryngology, 2010.

Chen, C. L., Szczesniak, M. M., & Cook, I. J. (2009). Evidence for oesophageal visceral hypersensitivity and aberrant symptom referral in patients with globus. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 21(11), 1142-e96.

Deary, I. J., Wilson, J. A., & Kelly, S. W. (1995). Globus pharyngis, personality, and psychological distress in the general population. Psychosomatics, 36(6), 570-577.

Drossman, D. A., & Hasler, W. L. (2016). Rome IV—functional GI disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1257-1261.

El‐Serag, H., Becher, A., & Jones, R. (2010). Systematic review: persistent reflux symptoms on proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care and community studies. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 32(6), 720-737.

Hajioff, D., & Lowe, D. (2004). The diagnostic value of barium swallow in globus syndrome. International journal of clinical practice, 58(1), 86-89.

Harar, R. P. S., Kumar, S., Saeed, M. A., & Gatland, D. J. (2004). Management of globus pharyngeus: review of 699 cases. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, 118(7), 522-527.

Harvey, P. R., Theron, B. T., & Trudgill, N. J. (2018). Managing a patient with globus pharyngeus. Frontline gastroenterology, 9(3), 208-212.

Jeon, H. K., Kim, G. H., Choi, M. K., Cheong, J. H., Baek, D. H., Lee, G. J., ... & Am Song, G. (2013). Clinical predictors for response to proton pump inhibitor treatment in patients with globus. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility, 19(1), 47.

Karkos, P. D., & Wilson, J. A. (2006). Empiric treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux with proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review. The Laryngoscope, 116(1), 144-148.

Khalil, H. S., Reddy, V. M., Bos‐Clark, M., Dowley, A., Pierce, M. H., Morris, C. P., & Jones, A. E. (2011). Speech therapy in the treatment of globus pharyngeus: how we do it. Clinical Otolaryngology, 36(4), 388-392.

Kirch, S., Gegg, R., Johns, M. M., & Rubin, A. D. (2013). Globus pharyngeus: effectiveness of treatment with proton pump inhibitors and gabapentin. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 122(8), 492-495.

Kortequee, S., Karkos, P. D., Atkinson, H., Sethi, N., Sylvester, D. C., Harar, R. S., ... & Issing, W. J. (2013). Management of globus pharyngeus. International Journal of Otolaryngology, 2013.

Kumar, Anand & Katz, Philip. (2013). Functional esophageal disorders: A review of diagnosis and management. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology. 7. 453-61. 10.1586/17474124.2013.811028.

Kwiatek, M. A., Mirza, F., Kahrilas, P. J., & Pandolfino, J. E. (2009). Hyperdynamic upper esophageal sphincter pressure: a manometric observation in patients reporting globus sensation. The American journal of gastroenterology, 104(2), 289.

Lee, B. E., & Kim, G. H. (2012). Globus pharyngeus: a review of its etiology, diagnosis and treatment. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG, 18(20), 2462.

Li W, Ren YP, Shi YY, Zhang L, Bu RF.Presentation, Management, and Outcome of Lingual Thyroglossal Duct Cyst in Pediatric and Adult Populations. J Craniofac Surg. 2019 Apr 12

Lorenz, R., Jorysz, G., & Clasen, M. (1993). The globus syndrome: value of flexible endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, 107(6), 535-537.

Moloy, P. J., & Charter, R. (1982). The globus symptom: incidence, therapeutic response, and age and sex relationships. Archives of Otolaryngology, 108(11), 740-744.

Moser, G., Wenzel-Abatzi, T. A., Stelzeneder, M., Wenzel, T., Weber, U., Wiesnagrotzki, S., ... & Pokieser, P. (1998). Globus sensation: pharyngoesophageal function, psychometric and psychiatric findings, and follow-up in 88 patients. Archives of internal medicine, 158(12), 1365-1373.

Oishi, N., Saito, K., Isogai, Y., Yabe, H., Inagaki, K., Naganishi, H., ... & Ogawa, K. (2013). Endoscopic investigation and evaluation of anxiety for the management of globus sensation. Auris Nasus Larynx, 40(2), 199-203.

Pollack, A., Charles, J., Harrison, C., & Britt, H. (2013). Globus hystericus. Australian family physician, 42(10), 683.

Robson KM, Lembo AJ.Globus sensation. Grover S, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc. https://www.uptodate.com(Accessed on February 25, 2019)

Rommel, N., Selleslagh, M., Vos, R., Holvoet, L., Depeyper, S., Altan, E., ... & Van Oudenhove, L. (2012). 137c Globus Patients are Characterized by Abnormal Sensitization of the Esophageal Body Upon Repeated Balloon Distensions. Gastroenterology, 142(5), S-35.

Rowley, H., O'dwyer, T. P., Timon, C. I., & Jones, A. S. (1995). The natural history of globus pharyngeus. The Laryngoscope, 105(10), 1118-1121.

Selleslagh, M., Van Oudenhove, L., Pauwels, A., Tack, J., & Rommel, N. (2014). The complexity of globus: a multidisciplinary perspective. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 11(4), 220.

Tang, B., Cai, H. D., Xie, H. L., Chen, D. Y., Jiang, S. M., & Jia, L. (2016). Epidemiology of globus symptoms and associated psychological factors in China. Journal of digestive diseases, 17(5), 319-324.

Thompson, W. G., & Heaton, K. W. (1982). Heartburn and globus in apparently healthy people. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 126(1), 46.

Timon, C., Cagney, D., O'Dwyer, T., & Walsh, M. (1991). Globus pharyngeus: long-term follow-up and prognostic factors. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 100(5), 351-354.

Tokashiki, R., Funato, N., & Suzuki, M. (2010). Globus sensation and increased upper esophageal sphincter pressure with distal esophageal acid perfusion. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 267(5), 737-741.

Wareing, M., Elias, A., & Mitchell, D. (1997). Management of globus sensation by the speech therapist. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 22(1), 39-42.

Webb, C. J., Makura, Z. G. G., Fenton, J. E., Jackson, S. R., McCormick, M. S., & Jones, A. S. (2000). Globus pharyngeus: a postal questionnaire survey of UK ENT consultants. Clinical Otolaryngology & Allied Sciences, 25(6), 566-569.

Weijenborg, P. W., de Schepper, H. S., Smout, A. J., & Bredenoord, A. J. (2015). Effects of antidepressants in patients with functional esophageal disorders or gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 13(2), 251-259.

You, L. Q., Liu, J., Jia, L., Jiang, S. M., & Wang, G. Q. (2013). Effect of low-dose amitriptyline on globus pharyngeus and its side effects. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG, 19(42), 7455.