see: Neural Crest Cell Tumors (PNT = peripheral neuroblastic tumors)

Case Report

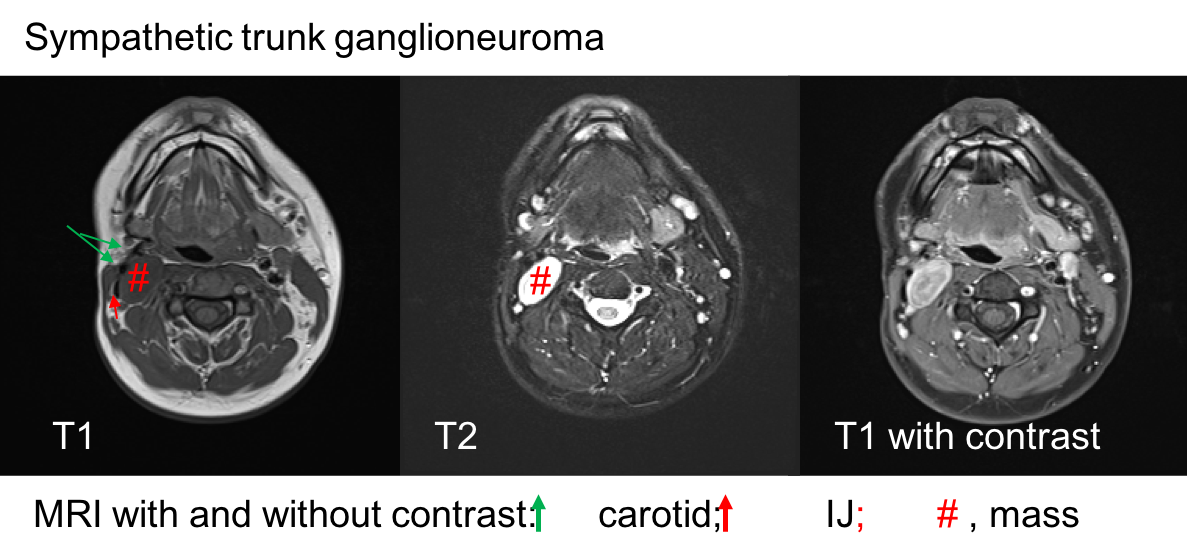

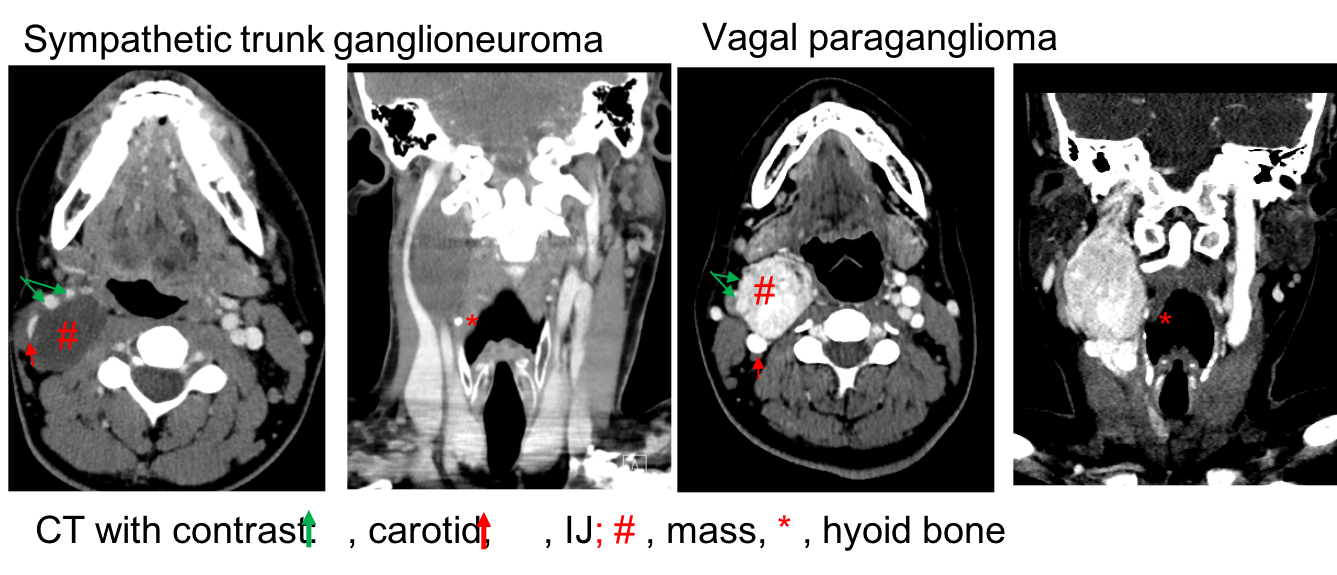

A 28 y.o. male with a history of childhood metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma treated with induction chemotherapy, right parotidectomy and neck dissection, followed by chemoradiation and left pulmonary lobectomy for recurrence. He presented to his local otolaryngologist for a right neck mass for 6 months. The mass was incidentally noticed when he was shaving. Otherwise, he was completely asymptomatic. The mass was located in the right level 2A area, pulsatile, mobile and nontender on palpation. The work-up included a CT neck with contrast that showed 2.2 x 2.2 x 4.2 cm hypodense, non-contrast enhanced mass in the right neck (Figure 1). MRI showed an isodense T1, hyperdese on T2 tumor with avid enhancementt (Figure 2). There was no “salt and pepper” appearance. In terms of its relationship with the major vessels in the neck, the mass was located medial to both the internal and external carotid arteries, and the internal jugular vein (Figure 1 and Fiture 2). A fine needle aspiration was then performed which suggested neurofibroma (neoplastic cells diffusely and strongly positive for S100 but negative for pankeratin, SMSA, desmin and myogennin). Patient denied family history of NF1. Decision was made to observe since the patient was asymptomatic. Ten months later, the patient presented to our clinic as he felt the size of the mass had increased during the interval. He otherwise continued to be asymptomatic. Given his past medical history of rhabdomyosarcoma and radiation, surgical intervention was considered. Intraoperatively, the tumor appeared to be well-circumscribed and located behind the carotid arteries, vagus nerve, as well as the internal jugular vein (Figure 3-5). There was a good plane that could be easily developed between the capsule of the mass and the surrounding tissues including the vagus nerve. Inferiorly, the tumor was firmly attached to the sympathetic trunk from which it was divided permitting mobilization of the tumor laterally and superiorly. The tumor was then meticulously traced towards the skull base and was then freed from its superior attachment at the C1 level. Postoperatively, the patient immediately developed right sided Horner’s syndrome as expected. His cranial nerves VII, X, XI and XII were completely normal at his one week postop visit.

Discussion

Ganglioneuroma (GN) are rare and slow-growing tumors that arise from sympathetic ganglion cells. They belong to the family of peripheral neuroblastic tumors (pNTs) which include neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma. GNs represent the final stage of maturation of pNTs thus are benign. Morphologically, GNs are encapsulated, non-vascular tumors comprised of large mature ganglion cells; whereas neuroblastomas are composed of small, primitive-appearing cells with dark nuclei scant cytoplasm and poorly defined cell borders growing in solid sheets.

pNTs are members of tumors derived from the neural crest cells. The neural crest cells are highly migratory and multipotent population that develop into many cell types and tissues throughout the body. Tumors arising from the neural crest cells are extremely diverse; the nomenclature is confusing. In general, tumors arising from the neural crest cells can be divided into 4 lineages: tumors of the sympathetic-adrenal lineage, tumors of the Schwann cell lineage, tumors of the melanocytic lineage (malignant melanoma), and multiple lineage tumor syndromes (MEN).

Neural Crest Cell Tumors (PNT's = peripheral neuroblastic tumors) (adapted from Maguire 2015)

|

Lineages |

Derived Tumors |

Links in Iowa Protocols |

|

Sympathetic-Adrenal |

Pheochromocytoma Paraganglioma Peripheral neuroblastic tumors (pNTs) including neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma. |

Carotid Body Tumor and Carotid Body Paraganglioma Case Example |

|

Schwann Cell |

Benign nerve sheath tumors Neurofibroma (when multiple - NF1) Schwanoma (when multiple NF2) Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) |

|

|

Melanocytic |

Melanoma |

|

|

Multiple tumors |

MEN 1 is not associated with neural crest derived tumors MEN 2A Medullary thyroid cancer arising from parafollicular C cells and Pheochromocytoma arising from pheochromocytes (chromaffin cells)of the adrenal medulla MEN 2B Diffuse gastrointestinal ganglioneuromatosis |

Comparison between sympathetic trunk ganglioneuroma and vagal paraganglioma:

Tumors of the sympathetic-adrenal lineage include pNTs, pheochromocytoma (PCC) and paraganglioma (PGL). Both PCC and PGLs are rare, vascularized neuroendocrine tumors that arise from paraganglia. Paraganglia are clusters of neuroendocrine cells dispersed throughout the body. The largest collection is in the adrenal medulla which gives rise to pheochromocytomas. The extraadrenal paraganglia include the paraverteral paraganglia (organs of Zuckerkandl), those associated with aorticopulmonary chain (the jugulotympanic ganglia, ganglion nodosum of the vagus, carotid bodies, and aortic bodies), and clusters located in the oral cavity, nose, nasopharynx, larynx, and orbit. The paravertebral paraganglia usually have sympathetic connection and contain chromaffin cells (pheochromocyte). As such, tumors arising from the paravertebral paraganglia are essentially "extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma" and frequently secret excess catecholamine. The major difference between them is that paravertebral paragangliomas secret norepinephrine whereas "intra-adrenal pheochromocytomas" secret epinephrine. This is because the enzyme that converts norepinephrine to epinephrine (phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase, PNMT) requires cortisol as a cofactor which exists in the adrenal medulla. Tumors arising from the paravertebral paraganglia are usually located outside of the HN area (chest, abdomen, and bladder). The paragangliomas in the HN area are frequently parasympathetic, comprised of chromaffin-negative cells. As such, paragangliomas in the HN area usually do not secret catecholamines. Morphologically, PGLs are highly vascularized, thin-encapsulated masses composed of clusters of chief cells in a highly vascular stroma with silver enhancement (Zellballen). PGLs can become malignant. However, there are no histologic criteria to differentiate benign from malignant paragangliomas because even benign paragangliomas exhibit cellular mitoses, nuclear pleomorphism, and capsular invasion. Malignant PGLs should be diagnosed if there is biopsy-proven metastasis to the regional LNs, lungs or bones. In general, there are about 4% of PGLs in the HN area are malignant (16% in Vagal PGL; 2-6% in Carotid body tumors and jugulotympanic PGLs).

Tumors of the Schwann cell lineage include both benign nerve sheath tumors (NSTs) and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs). Benign NSTs primarily include neurofibroma and schwannoma. Although they both arise from Schwann cell lineage, they are pathologically and genetically different. Schwannomas are well-circumscribed, encapsulated masses that are attached to the nerve or splay the nerve fibers which are usually incorporated into the capsule. Histologically, schwannomas are entirely made up of benign neoplastic Schwann cells, presented as two growth patterns: Antoni A, which exhibits high density of neoplastic Schwann cells arranged in fascicles with little stromal matrix, and Antoni B, which exhibits low cellularity along with microcysts and myxoid changes. In contrast, neurofibromas are unencapsulated masses comprised of a mixture of neoplastic Schwann cells, perineurial-like cells and fibroblasts. The fibers of involved nerve are usually intermixed with tumor components, making it impossible to separate the lesion from the nerve. The vast majority of both schwannomas and neurofibromasoccur sporadically and singly. Multiple schwannomas are associated with NF 2 whereas multipleneurofibromas are associated with NF1. MPNSTs can arise from pre-existing neurofibroma. In patients with NF1, the risk of developing an MPNST is about 8-13%. Malignant transformation of schwannomas is extremely rare. Such change is only reported in patients with melanotic schwannomas.

Recently, perineuromas are categorized as another form of benign NSTs. However, these tumors are comprised of perineural cells, which is not derived from neural crest cells but local mesenchymal cells. They are negative for S100 but positive for EMA (epithelial membrane antigen and claudin-1 (a membrane proteins of the tight junction). Similar to the case in neurofibromas, the nerve fibers in perineuroma also course through the tumor.

MEN is an autosome dominant inherited endocrine cancer syndrome subcategorized as MEN 1, MEN 2A and 2B based on overlapping clinical phenotypes. MEN 2A/B but not MEN 1 is associated with neural crest cell-derived tumors. For instance, MEN 2A is associated with medullary thyroid cancer arising from parafollicular C cells and pheochromocytoma arising from pheochromocytes (chromaffin cells)of the adrenal medulla. MEN 2B is associated with diffuse gastrointestinal ganglioneuromatosis. The mechanism behind is due to the mutation of RET which is required for the migration of neural crest cells into foregut and the subsequent colonization and differentiation. While MEN2B frequently presents with diffuse gastrointestinal ganglioneuromatosis, mutation of RETin sporadic pNTs remains controversial. Several gene mutations have been thought to be associated with the development of pNTs. For instance, studies have shown that PHOX2B mutation is associated with both familial and sporadic NB. Amplification of MYCN, a gene encoding a Myc family transcription factor, is found in a quarter of sporadic NB and associated with worse prognosis.

GNs are non-vascularized tumors. As such, GNs appear to be hypodense masses without significant enhancement (Figure 1). On MRI scan, our case exhibited an isodense T1, hyperdense on T2, avidly enhanced tumor (Figure 2), lacking the“salt and pepper” appearance which is commonly seen in pateints with PGLs (Links in Iowa Protocols).

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Modified Operative Report for ganglioneuroma of sympathetic chain

Patient and patient family identified in a surgical pre-holding area. Patient denied changes in his general health as was included in an updated history and physical examination. Indications risks benefits and alternatives was further discussed with the patient and his family. They verbalized full understanding and wished to proceed with the scheduled procedure. The surgical site was marked and initialled with the consent was reviewed.

The patient was then brought to the operating room and placed supine position. Transoral intubation with NIMS (nerve integrity monitoring system = EMG ) endotracheal tube was performed by anesthesia without difficulty. Laryngeal nerve monitor was used during the entire procedure. The table was rotated to position the paitent's head 180° away from anesthesia team. His arms were tucked with the bony eminences padded. Patient was prepped and draped in standard fashion. A formal timeout was performed.

Previous old scar was identified on the right side of the neck. 1% lidocaine was given. The old incision was marked. A 15 blade was used to make incision through the platysma. Platysmal flap was then raised superiorly and inferiorly. There was one external jugular lymph node was isolated and sent for pathology. The great auricular nerve was identified posteriorly on the SCM, which was traced superiorly and preserved. The submandibular gland was identified and mobilized anteriorly. The digastric muscle posterior belly was identified and was traced posteriorly. The hypoglossal nerve was identified and then traced posteriorly with scar tissue identified around its superior (more proximal) section thought to represent changes from previous surgery. The ansa hypoglossal was identified and traced inferiorly and well preserved in preparation for possible reinnervation procedure (ansa to recurrent laryngeal nerve) should the vagus nerve need to be sacrificed.

The anterior border of the SCM was identified with de-investing of the anterior fascia permitting lateral traction on the muscle to reveal the carotid sheath. The carotid sheath was then opened longitudinally. The internal jugular vein and the carotid artery were then separated and the vagus nerve was identified along its course and confirmed intact.

The tumor was immediately identified posterior to the vagus nerve and identified as separate from it permitting the vagus nerve to be freed from tumor.

Superiorly, the superior laryngeal nerve was identified and preserved. The tumor was then dissected away from the vagus nerve and surrounding tissues. Inferiorly, the tumor was firmly attached to the sympathetic trunk from which it was divided permitting mobilization of the tumor laterally and superiorly. The tumor was then meticulously dissected away from the surrounding tissue towards the skull base at the C1 level. The tumor was then freed from its superior attachment.

The wound was then irrigated with hemostasis was achieved (including a moment of sustained positive pressure from the anesthesia team to ensure no additional bleeding).

The vagus nerve was then stimulated with good signal from NIMS (nerve integrity monitoring system) endotracheal tube. The hypoglossal nerve was not stimulable proximally but was successfully stimulated distally.

The wound was then further examined with anesthesia repeating sustained positive pressure up to 40 with no bleeding was appreciated.

A #10 fully perforated Jackson Pratt drain was then placed. The SCM fascia was then approximated loosely with 3. 0 vicryl to cover the major vessels. The platysma was closed using 3.0 vicryl. Dermis was closed using 5.0 monocryl. The skin was closed using 4.0 nylon (running).

This then concluded the procedure. Pt was then turned over back to the anesthesia team for extubation.

References

Maguire LH, Thomas AR, Goldstein AM. Tumors of the neural crest: Common themes in development and cancer. Dev Dyn. 2015 Mar;244(3):311-22

Kumar V, Abbas, A, Fousto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th Edition.

Rankine AJ, Filion PR, Platten MA, Spagnolo DV. Perineurioma: a clinicopathological study of eight cases. Pathology. 2004 Aug;36(4):309-15.

Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Soft tissue perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 81 cases including those with atypical histologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005 Jul;29(7):845-58.

Bunge MB, Wood PM, Tynan LB, Bates ML, Sanes JR. Perineurium originates from fibroblasts: Demonstration in vitro with a retroviral marker. Science 243: 229–231.

Albuquerque BS, Farias TP, Dias FL, Torman D. Surgical management of parapharyngeal ganglioneuroma: case report and review of the literature. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2013;75(4):240-4. doi: 10.1159/000353550. Epub 2013 Jul 26. PMID: 23900231.