Iowa Thoracic Surgery

Content compiled by Evgeny V. Arshava, MD, John C. Keech, MD, Melissa Tvedte, ARNP, Kelley Mcghlaghlin, RN, Joan Ricks-McGillin, RN, Kalpaj R. Parekh, MBBS

Please direct questions and comments to Evgeny V. Arshava, MD evgeny-arshava@uiowa.edu

For general considerations, basic anatomy and choice of the approach for an esophagectomy see: Esophagectomy for an Esophageal Cancer: General Considerations and Choice of Operation

see also:

- Cervical gastroesophageal anastomosis

- Arshava Transhiatal retractor

- Three-Field Esophagectomy (McKeown): Laparotomy and right thoracotomy (thoracoscopy) with cervical anastomosis.

- Thoracic duct ligation.

- Chylothorax.

- Reconstruction After Total Laryngectomy ( with gastropharyngeal anastomosis)

- Esophageal Reflux Precautions

- Esophagoscopy with narrow band imaging (NBI) for Reflux Esophagitis

- Esophageal Myotomy and Diverticulectomy for Epiphrenic and Midesophageal Diverticula

INDICATIONS

- Carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction and lower third of the esophagus

- Early stage (T1a) carcinoma not amenable to endoscopic mucosal resection

- T1b–T4a after preoperative chemoradiation

- Note: T1b – T2, N0 low - risk lesions (well differentiated and < 2 cm) proceed to esophagectomy without nCRT

- End-stage benign strictures of the esophagus not amenable to transoral dilations (caustic injury, peptic structures)

CONTRAINDICATIONS

- Tracheobronchial, mediastinal, and intraabdominal structures invasion (T4b)

- Stage IV disease (with exception of selected patients with limited celiac lymph node metastasis—M1a stage IVa)

- Advanced physiologic (not chronologic) age and frailty

- Prohibitive co-morbidities

ANESTHESIA CONSIDERATIONS

General

- Epidural

- Two large-bore peripheral intravenous (IV) needles

- Radial arterial line

- Central venous line for selected patients only (via right neck)

- Blood type and cross

- Cefazolin within 1 h of the incision

Special

- Patient supine on a deflated bean bag (in case of emergent need for repositioning and thoracotomy)

- Shoulder roll, neck slightly hyperextended and turned right

- Arms tucked

- Single-lumen endotracheal tube

- Mean arterial pressure (MAP) is kept >65 mmHg (to optimize conduit perfusion)

- No vasopressors can be started without notifying the surgeon. Hypotension can almost often be managed with volume expansion.

NURSING CONSIDERATIONS

Instrumentation and Equipment

Standard

- Major chest tray

- Thoracic tray

- Energy device

- Lighted transhiatal retractor (narrow and wide in standard and bariatric depths)

- The table-mounted retractor

- Endoscopic linear cutting stapler

Special

- Saratoga sump drain or chest tube (for gastric conduit positioning)

- Doppler probe (available in room for obese patients)

- Magnetic nasal bridle

Medications

- Botox 200 units diluted in 8 mL of normal saline (optional per surgeon preference)

- Prep and Drape

- Standard prep using chlorhexidine solution

- Field includes mandible to pubis, between bilateral midaxillary lines, including both shoulders.

- Neck is draped just below the left ear lobe.

- Transparent incise drape

- Drains and Dressings

- Jackson-Pratt bulb drains, or Penrose drain

- 32 Fr chest tubes × 2

- 16 or 18 Fr nasogastric (NG) tube

OPERATIVE PROCEDURE

Abdominal Phase

- A supraumbilical incision is made. An optional excision of the xiphoid process for a deep and narrow chest may be considered.

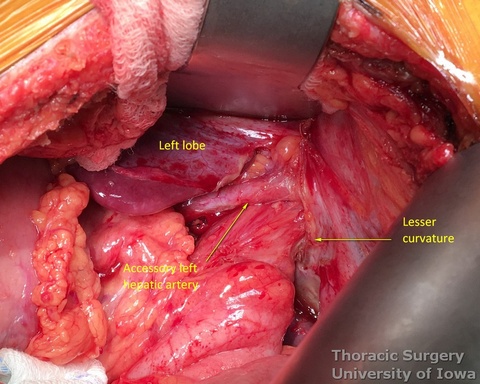

- Division of the falciform and left triangular ligament to retract the left lobe of the liver.

- The table-mounted retractor is deployed, and abdominal exploration for metastatic disease is performed.

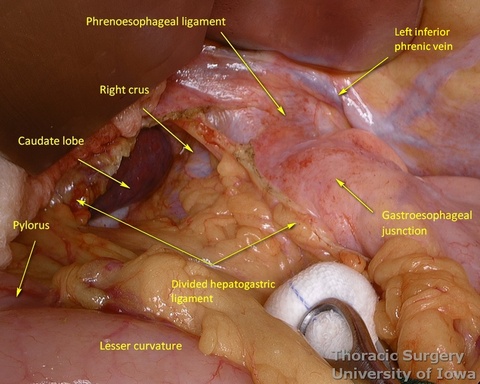

- The pars flaccida is incised and the gastrohepatic ligament is completely opened towards the esophageal hiatus.

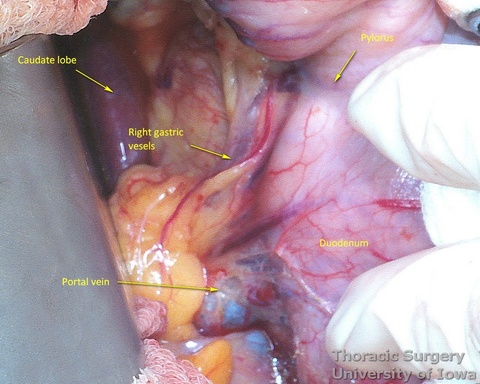

- The right gastric artery is preserved

- The replaced/accessory left hepatic artery, if present, can be divided.

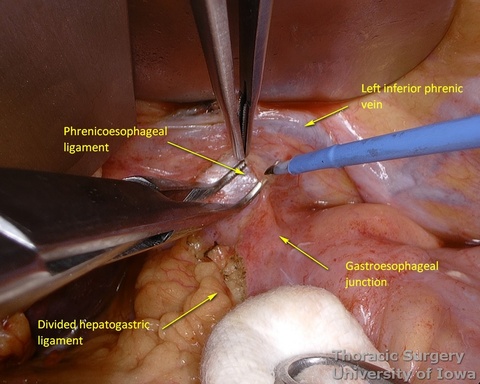

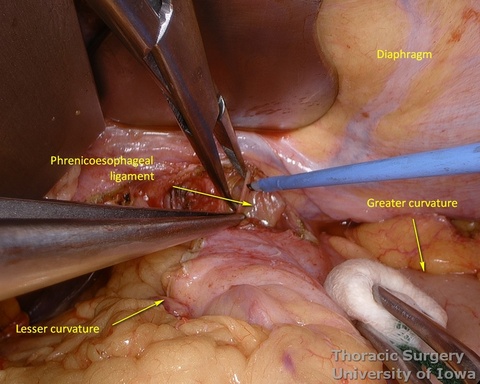

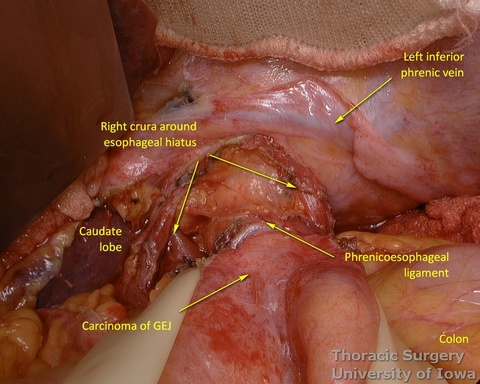

- Phrenoeosophagial ligament is formed by the transversalis fascia of abdomen and endothoracic fascia and is covered with the peritoneum. Thicker upper leaflet ascends obliquely and fuses with the adventitia of the esophagus above the diaphragm. The thinner lower leaflet runs caudally and attaches to the esophageal wall just cranial to the angle of His. The triangular space between the leaflets is filled with the perihiatal fat pad.

- The peritoneum is incised around the hiatus.

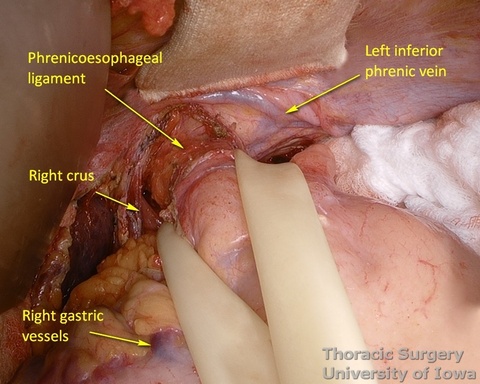

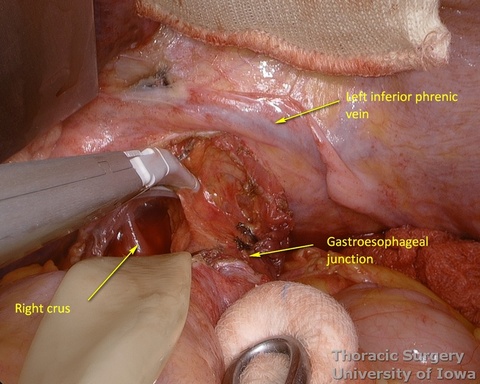

- The phrenoesophageal ligament is divided and the right crus dissected.

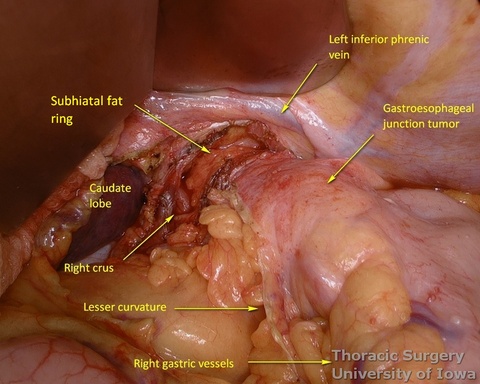

- Subhiatal fat ring is exposed after division of the lower leaflet of the phrenoesophageal ligament

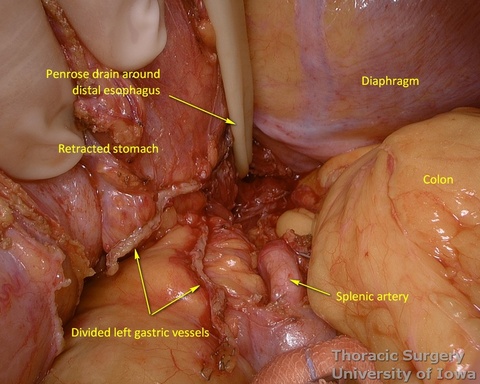

- The abdominal esophagus, periesophageal fat, and nodes are dissected and encircled with a Penrose drain for retraction.

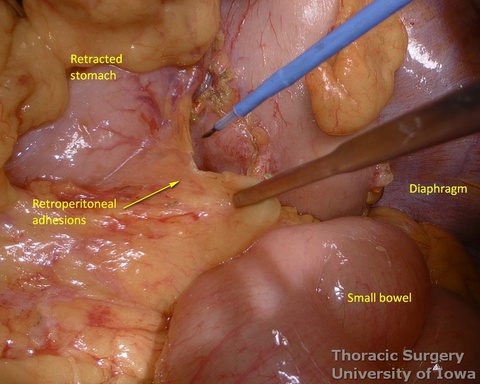

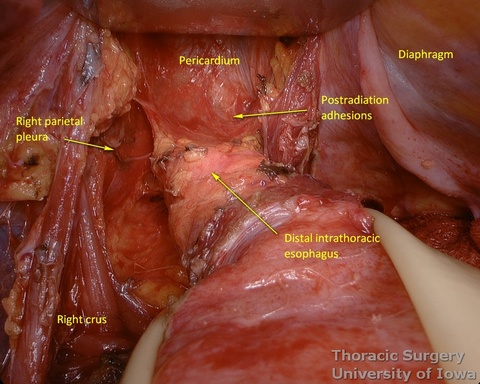

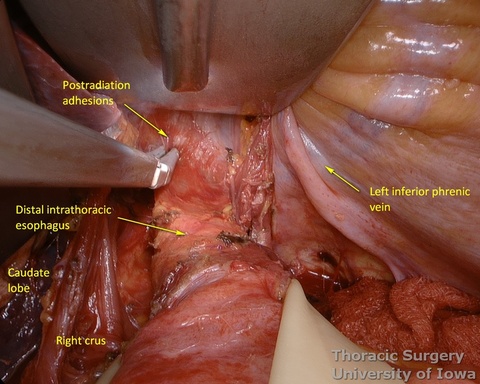

- The mediastinum is entered with the combination of sharp and blunt dissection. Note that postradiation adhesions become denser 4-6 weeks after neoadjuvant treatment.

- Once the mediastinum entered, the manual palpation through the hiatus is performed to assess mobility of the esophagus. Tumor is “rocked” from side to side to make sure it is not adherent to the aorta, prevertebral fascia, or mediastinal structures, thus assuring the feasibility of transhiatal approach or the need to perform transthoracic dissection. This should also be planned based on preoperative imaging.

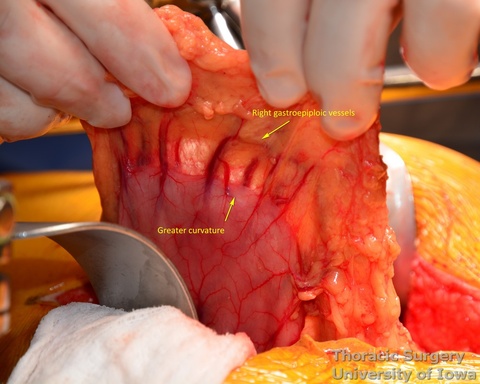

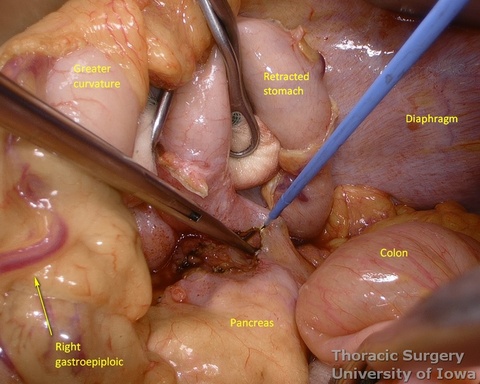

- Procced with mobilization of the stomach. The course of the right gastroepiploic artery is determined.

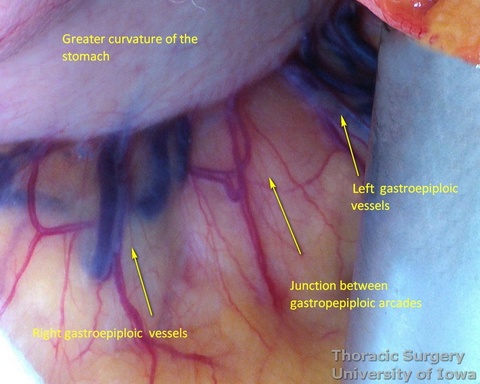

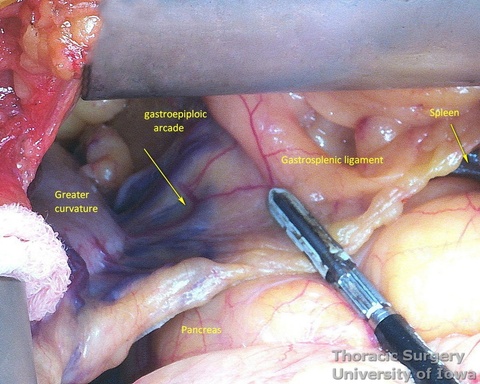

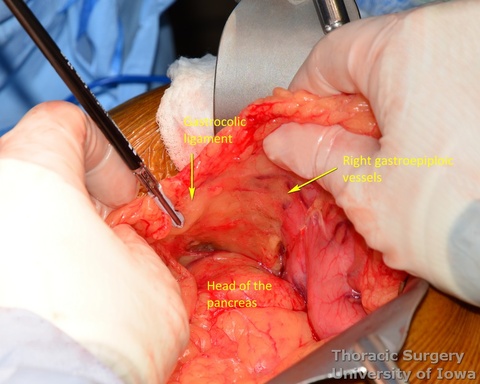

- The gastrocolic ligament is incised in its avascular portion between the terminal branches of the right and left gastroepiploic vessels, and the lesser sac is entered.

- The gastrosplenic ligament is divided towards the hiatus, taking care to stay away from the gastroepiploic arcade.

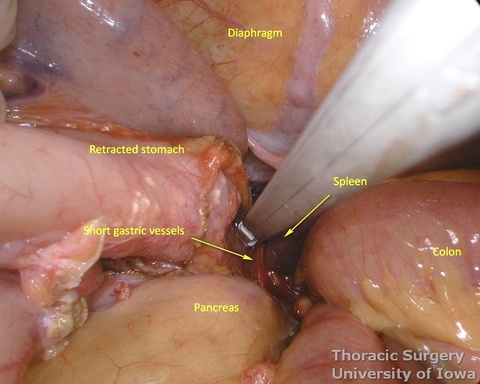

- Divide short gastric vessels with an energy device with care to avoid traction injury of the spleen.

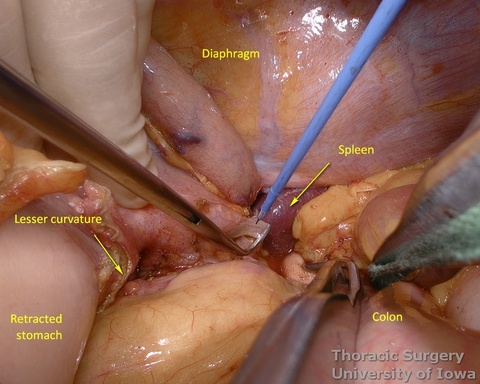

- Fundus of the stomach is dissected free all the way to the esophageal hiatus dividing gastro-phenic ligament and remaining adhesions.

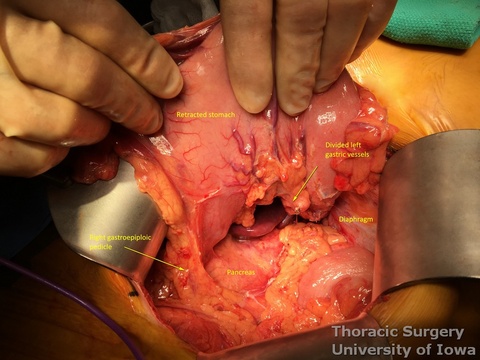

- The greater curvature of the stomach is then mobilized towards the pylorus, dividing the gastrocolic ligament no closer to than 1.5–2 cm to the right gastroepiploic vessels, while protecting the vessels with the fingers of the retracting hand. In morbidly obese patients the right gastroepiploic artery may not be visible or palpable. A Doppler probe is used then to identify its course and origin from the gastroduodenal artery.

- Posterior adhesions of the stomach are taken down.

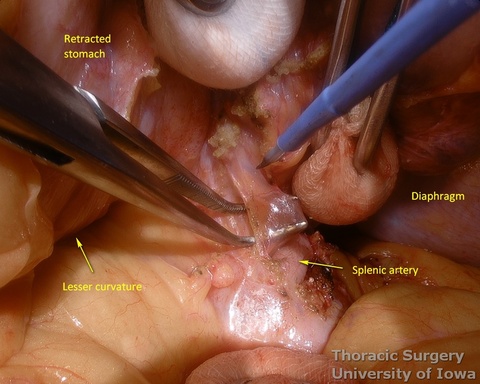

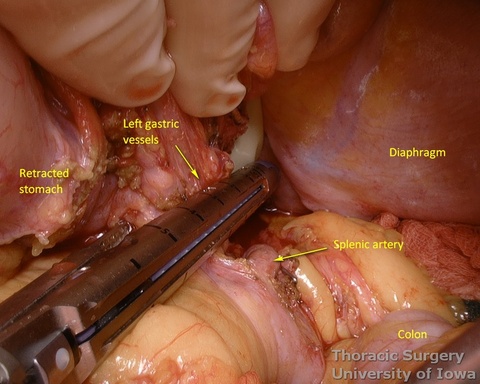

- Peritoneum is incised, protecting the splenic artery and pancreas. 1-2 mm posterior gastric artery, originating from the proximal splenic artery fs present (in half of individuals) and is divided.

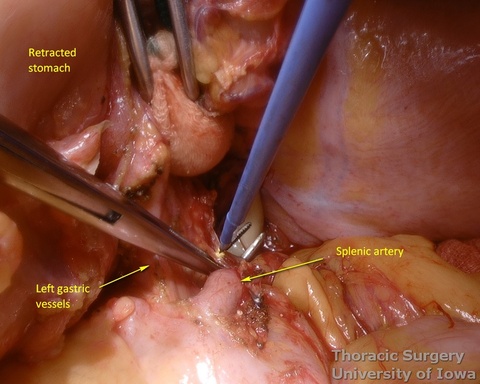

- Once the stomach is mobilized and reflected anteriorly, the left gastric vascular pedicle is identified and dissected close to the origin for adequate lymphadenectomy. Care is taken to not injure splenic artery and pancreas.

- Postradiation adhesions may be dense.

- Left gastric vessels are divided with an endoscopic linear cutting stapler proximally, including all adjacent lymph nodes in the specimen.

- Adequate mobility of the fully mobilized stomach is assured by the ability to bring the pylorus towards the hiatus.

- The Kocher maneuver is almost never needed.

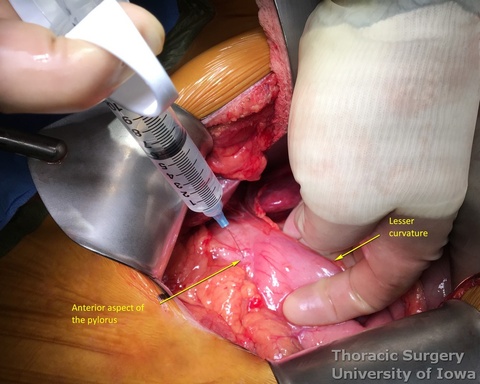

- Injection of 200 units of Botox diluted in 8 mL of normal saline is performed anteriorly and posteriorly into the pylorus (divided in 2 mL portions in four quadrants) to improve gastric emptying postoperatively. No pyloromyotomy is needed then.

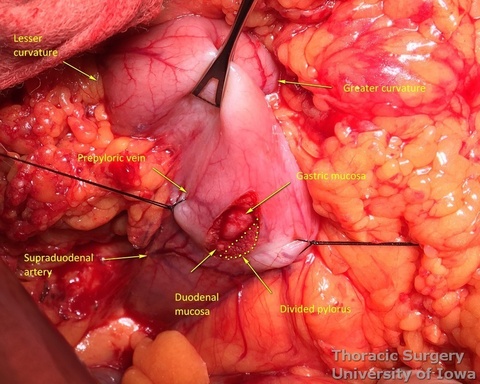

- Alternatively, pyloromyotomy can be performed using an electric cautery to divide the pyloric muscle.

Cervical Phase (for cervical phase and anastomosis operative images, see: Cervical gastroesophageal anastomosis page)

- Cricoid cartilage is the surface landmark for the cricopharyngeus muscle (functional upper esophageal sphincter) at the beginning of the esophagus.

- A 6 cm skin incision is made along the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle, starting at the sternal notch and extending to the level of the cricoid cartilage.

- The platysma is divided, and dissection is continued medially to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the carotid sheath, and laterally to the trachea and the thyroid.

- The omohyoid muscle is divided with electrocautery.

- Strap muscles are divided with electrocautery.

- Inferior thyroid artery is an internal landmark located at the level of the cricoid cartilage and the cricopharyngeus muscle (functional upper esophageal sphincter).

- The middle thyroid vein and the inferior thyroid artery are divided.

- Care is taken to protect the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Use a finger to retract the trachea, not the metal retractor.

- The deep cervical fascia is incised and, with further dissection towards the vertebral bodies, the esophagus is identified, gently mobilized circumferentially, and encircled with a Penrose drain.

- The esophagus is further dissected into the superior mediastinum with gentle traction and finger dissection.

Transhiatal Phase

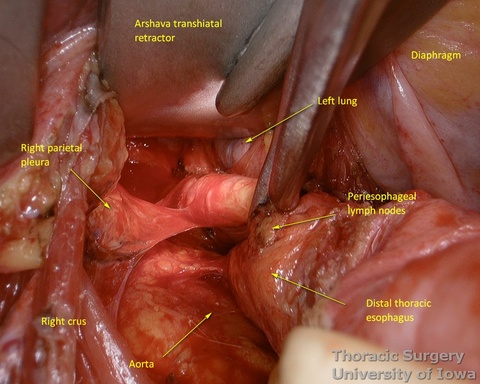

- The transhiatal retractor (See Arshava transhiatal retractor) is positioned in the esophageal hiatus.

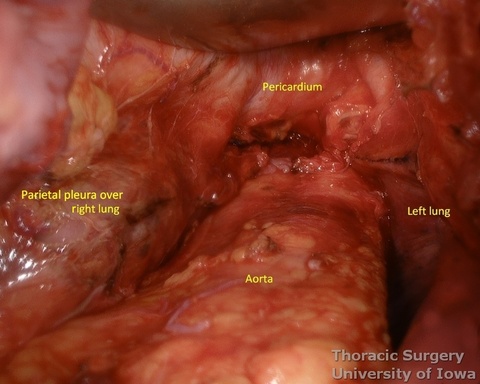

- The illuminated transhiatal retractor is advanced into posterior mediastinum under direct vision

- The distal thoracic esophagus is visualized.

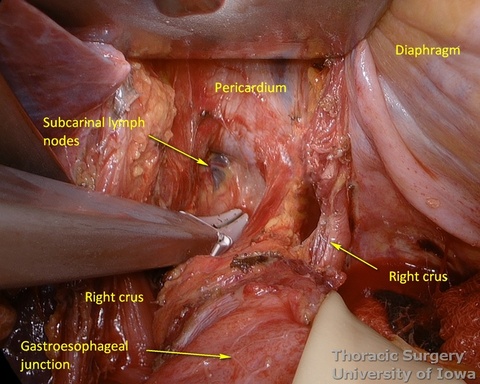

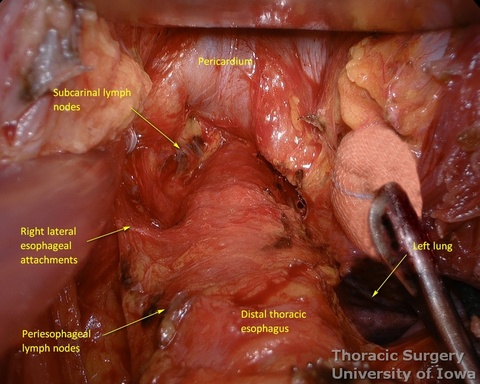

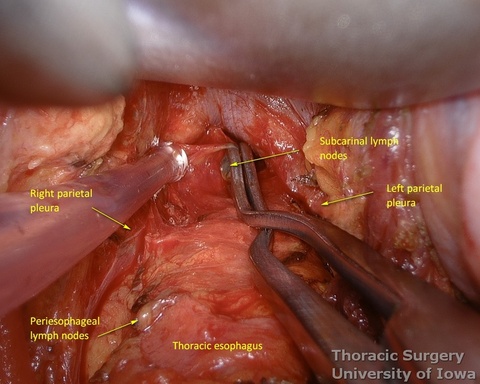

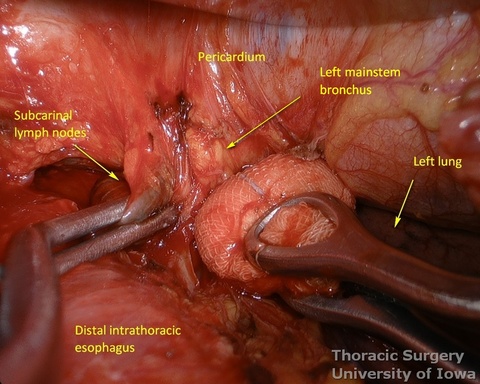

- Esophagus is circumferentially mobilized under direct vision using combination of sharp and blunt dissection up to the level of the carina.

- Right lateral esophageal “ligament” (attachments to the parietale pleura, pulmonary ligaments and branches of vagal nerves) is exposed are divided under direct vision

- Left lateral esophageal attachments (“ligament") is divided under direct vision

- Aorto-pleural and aorto-esophageal ligaments divide posterior mediastinum into peri-esophageal and peri-aortic (thoracic duct and azygos vein) compartments. They may be distinctly seen in some patients.

- Esophageal arteries (aorto-esophageal branches) and vagal nerves are divided under direct vision using the energy device.

- Periesophageal and subcarinal lymph nodes are dissected separately or en-block with the esophagus under direct vision.

- Use of energy devices should be limited near the membranous portions of the airways.

- Dissection of the distal and mid esophagus is completed using a combination of an energy device and suction tips.

- Through the abdomen, the hiatus is enlarged to allow a hand entry. Circumferential midesophageal and proximal esophageal dissection is gently completed in the superior mediastinum with fingers sequentially through the neck incision (along with gently traction on the cervical esophagus) and hiatus (along with gently traction on the Penrose around the gastroesophageal junction).

- Prolonged periods of hypotension and use of a vasopressors must be avoided during manual dissection.

- The transhiatal retractor is reinserted, if needed, to divide remaining adhesions under the direct vision and to assure hemostasis.

- Once the intrathoracic esophagus is mobile, the esophagus is divided with a linear stapler in the neck incision (NG tube is pulled back), preserving as much cervical esophagus as possible (usually 8-10 cm distal to the cricopharyngeus muscle)

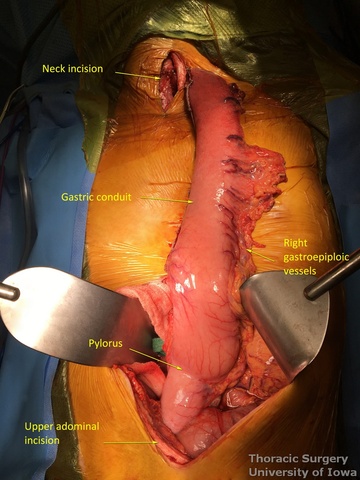

- The stomach and lower thoracic esophagus are delivered out of the abdominal incision.

- The mediastinum is inspected for bleeding with the use of the lighted transhiatal retractor. The mediastinum is packed.

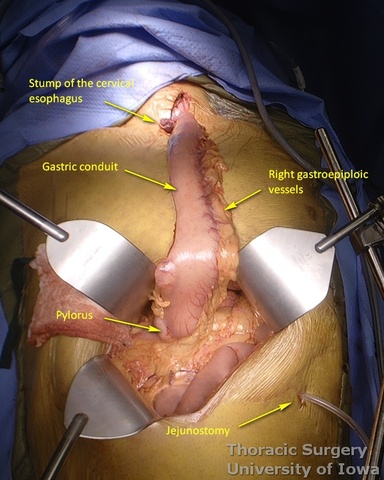

Conduit Preparation and Positioning

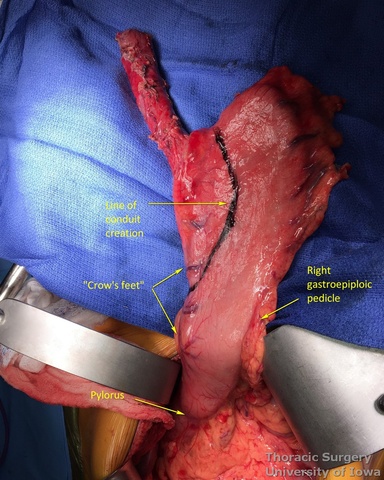

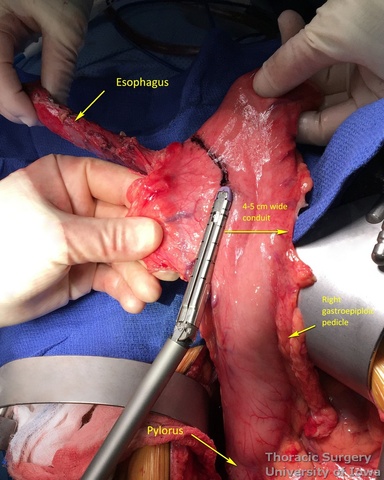

- At approximately the level of the third large vein (accompanying vagal “crow’s foot”) along the lesser curvature, lymphatic tissue and vessels are mobilized and divided to expose the gastric wall.

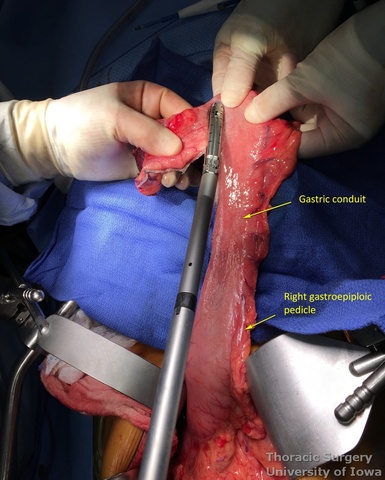

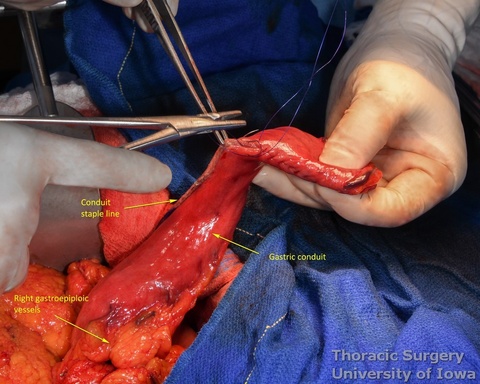

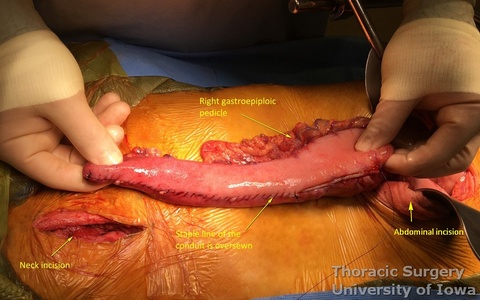

- Starting from the lesser curvature of the stomach, several stapler loads are sequentially fired towards the fundus of the stomach, thus creating a 4–5 cm wide gastric conduit and ensuring a 5 cm margin distal to the tumor. Depending on the thickness of the stomach, medium purple or thick black (alternatively blue or green, depending on manufacturer) loads are used.

- Gastric conduit should reach the cervical incision.

- The gastric conduit stapler line is then oversewn with a running 4-0 (KP and JK) or 3-0 (EA) PDS.

- A Saratoga sump drain (or chest tube) is advanced from the cervical incision through the chest into the abdomen. A Penrose drain is sewn to the anterior wall of the gastric tube (in the area of expected gastrotomy for the anastomosis) and tied over the sump drain.

- The gastric conduit is gently delivered through the mediastinum into the neck without torsion.

- Bilateral chest tubes are placed.

Cervical Anastomosis (for cervical phase and anastomosis operative images, see: Cervical gastroesophageal anastomosis page)

- Cervical anastomosis is performed using the Modified Collard technique as described by Orringer.

- The site of the gastrotomy is marked.

- In rare cases of a long available gastric tube, its tip can be shortened (as it is prone to ischemia) within the cervical incision with the linear cutting stapler before starting the anastomosis.

- Packing the corner of a sponge under the gastric tip into the mediastinum at this point decreases slippage of the stomach into the mediastinum until the anastomosis is complete. The esophagus is aligned over the gastric tip.

- The staple line of the esophagus is sharply removed. The NG tube is advanced out of the esophagus to help retract and align the esophagus for the anastomosis (alternatively pulled back proximally into the esophagus per surgeon preference).

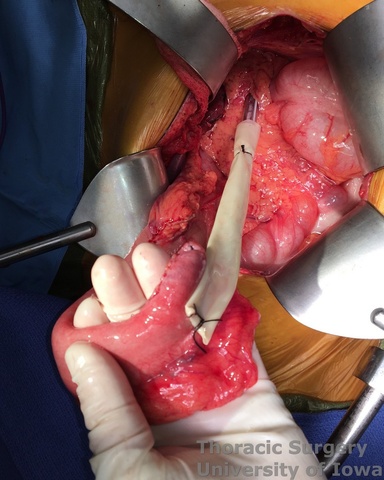

- A gastrotomy is performed 3 cm distal to the tip of the staple line. Interrupted, full-thickness sutures are placed to align the midpoints posteriorly and anteriorly on the gastric conduit and esophagus for the anastomosis.

- A 30 mm long linear cutting stapler is placed into the cervical esophagus and gastric conduit to create the posterior wall of the anastomosis.

- Before the stapler is fired, additional seromuscular stitches are used to secure the tip of the conduit to the esophagus on each side proximally. The full-thickness sutures for the running inner layer are placed into opposite corners at this point as well.

- The stapler is fired to create the back wall of the anastomosis.

- An NG tube is advanced through the anastomosis under direct visualization and positioned near the pylorus. This is confirmed by palpation through the abdomen at the end of the case before the NG tube is firmly secured at the nose.

- The anterior aspect of the anastomosis is then completed with a full-thickness, running inner full-thickness layer of 3-0 (EA) or 4-0 PDS (KP, JK) sutures run from opposite corners and tied in the middle.

- An interrupted seromuscular layer of or 4-0 silk (KP, JK) or 3-0 Vicryl (EA) are used for the outer layer.

- The supporting gastric conduit sponge can be removed at this point to allow anastomosis to retract behind the manubrium.

- A 10 Fr Jackson-Pratt (KP, EA) or Penrose (JK) is placed by the anastomosis and directed into the superior mediastinum along the conduit.

- The platysma is loosely approximated to the sternocleidomastoid muscle with three or four interrupted absorbable sutures. The skin is closed with loose running 4-0 Nylon.

Completion of the Abdominal Phase

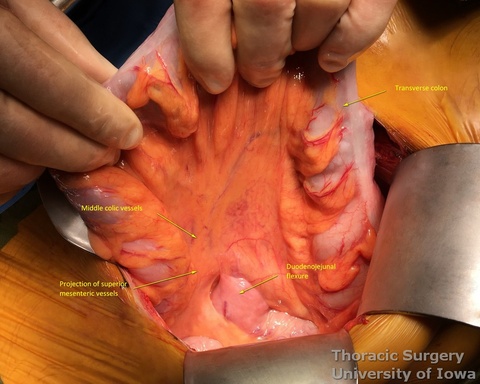

- The site for the feeding jejunostomy is located 20 cm distal to the duodenojejunal flexure (commonly and inaccurately called "ligament of Treitz", which is located in the retroperitoneum and is not visible)

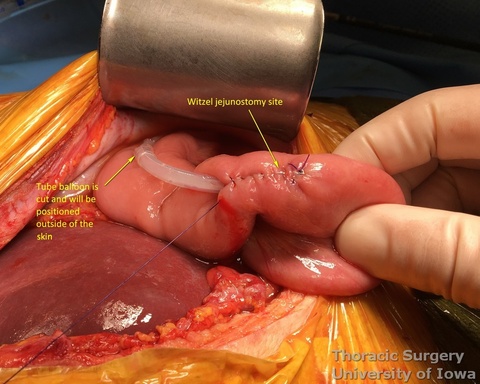

- 16 Fr feeding Witzel (KP, EA) or Stamm (JK) or jejunostomy is placed (see: Witzel feeding jejunostomy)

- Hemostasis in the abdomen is assured. Sponge counts are confirmed.

- The fascia is closed with a #1 running absorbable suture.

- The skin is closed with subcuticular sutures. Surgical dressing or skin adhesive is used to cover the incision.

- The NG tube is flushed to confirm its patency, and it is secured to the nose with tape or a magnetic nasal bridle.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

General

- The patient is extubated in the operating room and admitted to a general care surgical ward.

- Pain control provided via epidural catheter limiting systemic narcotic analgesics.

- CXR is obtained immediately postoperatively. Daily CXR are not needed unless a change was made in the chest tube management or patient’s condition changes.

- Isotonic fluids are used to maintain euvolemic balance, with close attention to in-and-out (I/O) fluid measurements.

- MAP goal is >65 (to maintain perfusion of the conduit)

- Perform urine output checks every 4 h. Consider removing indwelling urinary catheter after post-operative day 3 if patient is at low risk for having benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Otherwise urinary catheter is kept while epidural is in place.

- The head of bed is maintained at 45o to reduce the risk of aspiration.

- NG tube to low (<80 mm Hg) continuous suction (LCS). Every 4 hours the drainage channel is flushed with 20 cc of fluid and the air channel is flushed with 20 cc of air to assure proper function of the NG tube. Functioning NG tube serves two goals:

- After esophagectomy patients are prone to aspiration (due to lack of gastric storage capacity, absence of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), and nonfunctional pylorus).

- Thus the functioning NG is aimed to fully decompress the gastric conduit, which is especially important during postoperative ileus.

- Additionally, the tip of the gastric conduit relies on the blood supply flow from the right gastroepiploic vessels through the intramural collaterals. Overdistention of the conduit may lead to low flow state in the collaterals, and hence ischemia of the anastomosis and leak.

- Chest tubes are maintained on suction at –20 cm H2O for 2-3 days (off suction for ambulation) to facilitate maximal lung expansion (for simplicity of use we prefer dry chamber units).

- Aggressive pulmonary care.

- Ambulation at least four times daily is recommended.

- Incentive spirometer every hour.

- Vibrating Positive Expiratory Pressure therapy every hour.

- Scheduled bronchodilators every 4 hours

- Scheduled chest physical therapy with the use of manual Pneumatic Percussor (on both lung fields every 4 hours while awake. Manual percussion even of the operative side is well tolerated by patients and may be more effective than a built-in percussion function of hospital beds.

- Use mucolytics inhalers as needed

- Postoperative prophylactic antibiotics are not indicated.

- Prophylactic heparin may be administered on POD 1

Specifics

- Postoperative day (POD) 1, 2—Pay attention to hemodynamics, I/O, electrolytes, pulmonary care, pain control, ambulation.

- POD 3—Start tube feedings and advance to goal as tolerated.

- POD 3—Start enteral route home medications.

- POD 4—NG and chest tubes are removed if there is no chyle leak while tube feedings at goal.

- POD 5-6 —Esophagram (water-soluble contrast followed by thin Barium) or JP drain fluid amylase analysis.

- The JP is removed if swallow is negative or amylase level is low.

- Neck incision Nylon suture is removed.

- Discharge with instructions to stay nil per os (NPO)

- If the patient develops a cervical wound infection (with or without obvious anastomotic leak), the incision is opened and packed. Such patients are at high risk for developing anastomotic stricture and should undergo endoscopy within 2–4 weeks, with dilation if needed.

OUTPATENT FOLLOW-UP

- Close telephone follow-up by thoracic nurses is recommended.

- Follow up in clinic in 2 weeks with CXR.

- Patient remains NPO for 3 weeks after esophagectomy.

- Patients are started on a clear liquid diet and, in increments of every 3 days, advanced to soft mechanical and then regular diet under close telephone follow-up by thoracic nurses.

- Follow up with PET computed tomography every 6 months for 3 years and then as clinically indicated as per National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines (https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx).

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References

Hulscher JB, Tijssen JG, Obertop H, van Lanschot JJ. Transthoracic versus transhiatal resection for carcinoma of the esophagus: A meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72: 306–313.

Orringer MB, Marshall B, Chang AC, et al. Two thousand transhiatal esophagectomies: changing trends, lessons learned. Ann Surg 2007;246:363–372.

Chernousov AF, Andrianov VA, Domrachev SA, Bogopol’ski PM. The experience of 1100 esophagoplasties [in Russian]. Khirurgiia (Mosk). 1998;(6):21-25.

Orringer M. Transhiatal esophagectomy. J. Deslauriers, S.L. Meyerson, A. Patterson, J.D. Cooper (Eds.), Pearson’s Thoracic and Esophageal Surgery (3rd ed.), Churchill Livingstone, London, UK (2007), pp. 563-583

Speicher JE, Gunn TM, Rossi NP, Iannettoni MD. Delay in oral feeding is associated with a decrease in anastomotic leak following transhiatal esophagectomy. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;30:476-484.

Arshava EV, Arshava AE, Keech JC, Weigel RJ, Parekh KR. Illuminated Transhiatal Retractor for Mediastinal Dissection During Transhiatal Esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020 Jan;109(1):e67-e69. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.07.076. Epub 2019 Sep 11

Weijs TJ, Goense L, van Rossum PSN, Meijer GJ, van Lier AL, Wessels FJ, Braat MN, Lips IM, Ruurda JP, Cuesta MA, van Hillegersberg R, Bleys RL. The peri-esophageal connective tissue layers and related compartments: visualization by histology and magnetic resonance imaging. J Anat. 2017 Feb;230(2):262-271. doi: 10.1111/joa.12552. Epub 2016 Sep 23.

Namm JP, Posner MC. Transhiatal Esophagectomy for Esophageal Cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016 Oct;26(10):752-756. Epub 2016 Aug 22.

Yeung JC, Bains MS, Barbetta A, Nobel T, DeMeester SR, Louie BE, Orringer MB, Martin LW, Reddy RM, Schlottmann F, Molena D. How Many Nodes Need to be Removed to Make Esophagectomy an Adequate Cancer Operation, and Does the Number Change When a Patient has Chemoradiotherapy Before Surgery? Ann Surg Oncol. 2020 Apr;27(4):1227-1232. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07870-2. Epub 2019 Oct 11

Espinoza-Mercado F et al. Does the Approach Matter? Comparing Survival in Robotic, Minimally Invasive, and Open Esophagectomies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019 Feb;107(2):378–385.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________