Note: last updated before 2015

Disc batteries can cause significant morbidity in a short period of time in the pediatric population. Approximately 60% of disc battery ingestions occur after removal from a device. This creates an emergent situation as esophageal perforation has been reported in at little as 5 hours. Injury occurs secondary to liquefactive necrosis, pressure necrosis and electrical charge.

Batteries that are 1.5 to 2 cm of size are much more likely to become lodged at the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle.

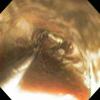

Imaging confirming location should be obtained prior to EMERGENT transfer to the OR for removal. The Double Lumen sign confirms the presence of a disc battery.

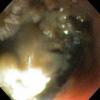

Initial injury is managed in the OR. This patient was placed into suspension with a Lindholm Laryngoscopy with removal under direct visualization with the aid of a Bruce Benjamin laryngeal lift maneuver. It is important to identify the direction of the negative pole of the battery for future assessment of this injury.

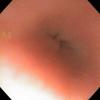

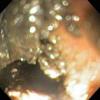

Esophagoscopy is performed at 24-48 hours after injury to evaluate the full extent of injury. If perforation of esophagus is identified, the procedure is aborted. The local injury was approximate 3 cm in size with 5 cm of inferior extension into the esophagus. A normal introitus is identified proximally.

A CR2032 disc battery is dropped into saline with continued, and immediate activity. Photos were obtained every 15 minutes for the first two hours, and every thirty minutes for a total of five hours, demonstrating activity from the negative pole during the entire time course.

Handout demonstrating disc battery activity:

![]() buttonbatterytimeline.pdf

buttonbatterytimeline.pdf

REFERENCES

Mortensen A, Hansen NF, Schiødt OM. Fatal aortoesophageal fistula caused by button battery ingestion in a 1-year-old child. Am J Emerg Med. 2010 Oct;28(8):984.e5-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.01.007. Epub 2010 Apr 2.

Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L. Preventing battery ingestions: an analysis of 8648 cases. Pediatrics. 2010 Jun;125(6):1178-83. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3038. Epub 2010 May 24.

Chang YJ, Chao HC, Kong MS, Lai MW. Clinical analysis of disc battery ingestion in children. Chang Gung Med J. 2004 Sep;27(9):673-7.

Yardeni D, Yardeni H, Coran AG, Golladay ES. Severe esophageal damage due to button battery ingestion: can it be prevented? Pediatr Surg Int. 2004 Jul;20(7):496-501. Epub 2004 Jun 22.

Litovitz TL. Button battery ingestions. A review of 56 cases. JAMA. 1983 May 13;249(18):2495-500. Review.

Russell RT, Cohen M, Billmire DF. Tracheoesophageal fistula following button battery ingestion: Successful non-operative management. J Pediatr Surg. 2013 Feb;48(2):441-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.11.040.

Temple DM, McNeese MC. Hazards of battery ingestion. Pediatrics 1983;71:100--3.

Litovitz T, Schmitz BF. Ingestion of cylindrical and button batteries: an analysis of 2,382 cases. Pediatrics 1992;89:747--57.

Brumbaugh DE, Colson SB, Sandoval JA, et al. Management of button battery-induced hemorrhage in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;52:585--9.

Hamilton JM, Schraff SA, Notrica DM. Severe injuries from coin cell battery ingestions: 2 case reports. J Pediatr Surg 2009;44:644--7.

Slamon NB, Hertzog JH, Penfil SH, Raphaely RC, Pizarro C, Derby CD. An unusual case of button battery-induced traumatic tracheoesophageal fistula. Pediatr Emerg Care 2008;24:313--6.

Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L, White NC, Marsolek M. Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics 2010;125:1168--77.