Radiation therapy is an important treatment for head and neck cancers, but it can also damage adjacent structures, such as the trachea and the esophagus, causing difficult-to-treat, breathing and swallowing problems.

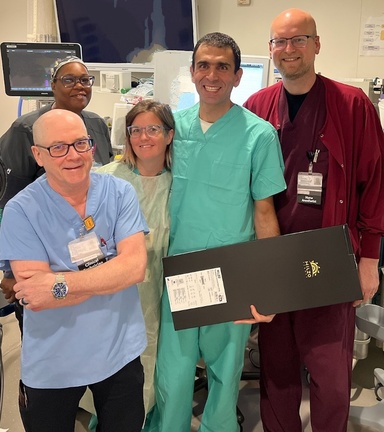

Driven to alleviate some of the serious side effects that can occur and improve patients' quality of life, University of Iowa Health Care gastroenterologist Rami El Abiad, MD, has developed an innovative approach to correct a rare yet severe form of radiation-induced esophageal abnormality, and has used a new stent in the treatment of tracheo-esophageal fistula.

The trachea and esophagus are two tubes that run side by side in the back of the throat; the esophagus carries food and drink to the stomach, and the trachea (or windpipe) goes to the lungs, allowing a person to breathe.

One rare complication of head and neck cancer radiotherapy is scar formation that narrows the esophagus and causes difficulty swallowing. An extreme form of narrowing termed esophageal atresia occurs when the esophagus closes completely. In such instances, even the saliva is unable to pass naturally, forcing the patient to constantly spit.

El Abiad and his team developed a simple approach that re-establishes esophageal continuity using a pediatric endoscopic and gentle pressure to gradually reopen the esophagus. Recently, he used the unique procedure to treat a patient who had been referred by his doctors who knew of El Abiad's expertise.

El Abiad and his team have also utilized a new stent to treat a second radiation-induced problem known as tracheo-esophageal fistula, where an abnormal connection forms between the esophagus and trachea causing food to enter the windpipe.

The UI team used a Hilzo UES stent with a shorter proximal phalange to bridge the fistula that was located high in the esophagus. The special design of the stent helped anchor it in place and decrease the pain and the sensation of a foreign object that would have occurred with a regular stent being placed so high up in the patient’s esophagus.

“This was the first case for placing this type of stent in the U.S.,” El Abiad notes. “Thoracic surgery was not an option for this patient, and he was high risk for a tracheal stent. After the procedure, the patient was virtually pain free and able to resume normal eating and drinking.”

El Abiad and his colleagues approach difficult cases like these with individualized treatment plans based on multidisciplinary input from physicians and providers in thoracic surgery and pulmonary service.

“We have been successful in devising a simple and novel technique to re-establish esophageal patency in the case of esophageal atresia, and have been fortunate to work with the medical industry to deploy the first of its kind esophageal stent in the US,” he says. “In doing so, we were able to make a difference by improving the quality of life for cancer patients by restoring the ability to swallow and to resume a normal diet.

“The drive for our work is to constantly search for simple, safe, and durable interventions to treat challenging GI conditions.”