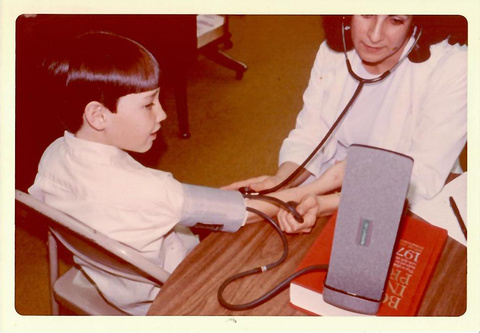

Ed Chamberlin has only vague memories of the day. He and his middle school classmates were lined up in a cramped basement in Muscatine while researchers from the University of Iowa took various vital statistics—height, weight, blood pressure, a few others.

They may have taken a blood sample too. He can’t remember.

It was the fall of 1970 and the start of a generations-spanning cardiovascular health study that continues to this day, 50 years later.

“As a kid, you don’t really have awareness of these things, but we’d been told about what we were doing and it seemed pretty important,” says Chamberlin, 64, who was a student at Muscatine’s Central Middle School at the time.

Important is a good way to describe the Muscatine Heart Study, one of the largest and longest-running investigations of cardiovascular disease ever undertaken by the University of Iowa. In its five decades of following Muscatineans who came of age in the decade of Watergate and disco, the study has made new discoveries about cardiovascular disease, what causes it, and how it might be prevented.

The study did nothing less than provide evidence that changed the way people think about the heart and cardiovascular disease by discovering that the risk factors that can be measured in children are related to cardiovascular disease in adults. If those risk factors are addressed when they’re still children, it could reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular disease when they’re older.

“It was important because it found hereditary influences on the development of heart disease and risk factors that could be found as early as childhood,” says Hal Schrott, an internist in the UI Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine and epidemiologist in the College of Public Health, who was involved with the study from 1973 until his retirement in 2003. “A lot of the findings from the study are taken for granted today, but it was plowing new ground then.”

To put into perspective how long the Muscatine study has lasted, Richard Nixon was in his first term when the first students were examined, and some of them would be drafted to fight the Vietnam War. The Mary Tyler Moore Show debuted on TV that fall, and telephones were rotary and owned by AT&T.

And so much of the knowledge we have today about what causes poor cardiovascular health was still unknown. The study was the brainchild of Ronald Lauer, a professor of pediatrics in the Carver College of Medicine who specialized in cardiology. He and his colleagues were inspired to follow up the findings of the Framingham Study, a landmark project begun in 1948 that investigated the causes and risk factors of cardiovascular disease by studying adults in Framingham, Massachusetts. But that study only measured risk factors beginning in adulthood. Why not, Lauer wondered, extend that study back to childhood?

“He wanted to take the findings of the Framingham Study down to children,” says Larry Mahoney (MD ’74), a pediatric cardiologist in the Carver College of Medicine who started with the study as a fellow in the 1970s and continued his involvement off and on until his retirement in 2012. “Nobody dreamed that you had to worry about heart risk with kids at that time. People thought that suddenly, in your 40s and 50s, you started having health issues. We didn’t even know what a healthy blood pressure or cholesterol level was for kids.”

His plan was a Framingham-style study that tested children for various risk factors for cardiovascular disease and then followed them into adulthood to see if those factors manifested as cardiovascular disease as adults. He chose Muscatine because it was easily accessible from Iowa City and because the school district had a stable enrollment with students he could track from start to finish.

“Most kids who started first grade in Muscatine graduated from high school there, so he could track them that whole time,” says Mahoney.

But even Lauer likely couldn’t imagine the study would still be going strong 50 years later.

The first phase followed more than 11,300 elementary, middle school, and high school students in public and private schools of Muscatine, conducting six examinations every other year from 1970 to 1981. The students underwent more than 26,000 examinations in those 11 years that measured such risk factors as body size, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and smoking behaviors.

A second phase, from 1982 to 1991, followed more than 2,500 of the first phase participants into young adulthood, continuing to measure those risk factors. A later phase followed about 900 participants into middle age and beyond, measuring risk factors by imaging the heart and arteries that revealed in some participants evidence of the early disease process and asking participants questions about their health, diet, physical activity, and family history.

Trudy Burns, an epidemiologist in the College of Public Health, says the study made numerous key discoveries about childhood cardiovascular health. The most important was that the cardiovascular disease factors identified in adults in the Framingham Study also are seen in childhood, and what happens when you’re a child has an impact on your adult health. Elevated levels of cholesterol, body mass index, blood pressure, and smoking increase the risk of disease as adults.

“If you have high cholesterol as a kid, you’ll probably have high cholesterol as an adult,” says Mahoney. “If you’re obese as a kid, you’ll probably be obese as an adult. It showed us how important it is to intervene with children who have these risk factors so they don’t lead to cardiovascular health issues when they grow up.”

Burns says numerous additional sub-studies were spun off from the main study. One, for instance, found that the relatives of obese children had a higher risk of cardiovascular death than the relatives of kids who were not obese. The relatives of obese children who had high blood pressure also had the highest risk.

One of Schrott’s studies examined adult family members of children who had elevated cholesterol levels and found an unexpectedly large number of them suffering from cardiovascular disease too.

“Family studies were an indirect way of investigating what might be in store for the kids if they could be followed for a long enough time, based on what was happening with their adult relatives,” says Burns, who joined the project in 1982 and took over as lead investigator when Lauer retired in 2005. (Lauer died in 2007.)

Burns says that while all of this is understood as conventional wisdom today, Muscatine was one of the studies that confirmed it through longitudinal observations.

“We think about this now and say, ‘Yeah, this is no big deal; we know all this,’ but it hadn’t been demonstrated at the time,” she says. “Results from the childhood studies were the first time these observations were made.”

Burns says one additional notable achievement has been the development of childhood blood pressure tables. Before the childhood studies there was only a vague understanding that a child’s blood pressure was lower than an adult’s. But exactly what that blood pressure should be, and how factors like age, weight, and height mattered, was unknown.

“People didn’t know what blood pressure looked like in children,” Burns says. “Was it like adults’? We didn’t know. Examinations of large numbers of children provided the data we needed to know what blood pressure looked like.”

With thousands of available measures from studies like Muscatine, investigators had the data they needed to describe what a healthy blood pressure should be for children at various stages of their development. The resulting tables have been tweaked a few times over the years, but they are still used today by pediatricians around the world as the standard for determining if their patients have a healthy blood pressure.

The project has so far led to more than 100 publications in research journals from Iowa faculty. Burns says the Muscatine study also became part of the International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort Consortium in 2009, consisting of childhood studies in Minneapolis; Cincinnati; Bogalusa, Louisiana; Finland; and Australia. The seven studies together represent data from more than 41,000 participants who were first examined during childhood and are now middle-aged adults. Burns says these studies are collaborating to investigate in even more finely grained detail the links between childhood risk factors and adult cardiovascular disease in participants followed for up to 50 years.

Muscatine is now in the midst of a new phase that will recruit 3,700 of the childhood participants from the 1970s for a full clinical exam to see how their health is progressing as they pass from middle to older age. Researchers set about contacting all of the original 11,300 participants in 2014 and by 2019 had managed to locate and recruit more than 6,400 of them, many of whom hadn’t been in contact with researchers in decades. All were asked to complete a survey regarding their current health and lifestyle habits, and those with a cardiovascular disease history were asked to provide consent for access to their medical records. More than 800 of the original participants have since died, and their cause of death was included.

Burns says 3,700 of those who completed the survey will be recruited for a clinical examination to track the same risk factors they’ve been following for 50 years. She says researchers hope to start that five-year investigation along with the other consortium studies in July 2021.

Researchers are also in the process of organizing and preserving the 50 years of Muscatine data in a repository so as to preserve institutional memory now that the first- and second-generation researchers and support staff are retiring.

The Muscatine community has vigorously embraced being a part of what is known local as “the heart study” from the start. Office and clinic space was set up in the Hotel Muscatine, where it still is today. All students in the city’s public and private schools were invited to participate in the first phase with their parents’ permission, and more than 70% took part. Muscatine civic groups rallied as well, including the Rotary Club and the Muscatine Health Support Foundation. Each group over the years provided the funding to purchase a trailer with fully equipped portable examining rooms. The trailers could be brought to different schools, making it easier and less disruptive for students to be examined.

“It was just awesome,” says Schrott, whose spinoff study of heart disease in students’ family members saw a participation rate of over 90%. “I’d never been part of a study that had those kinds of numbers.”

Matt Rivera doesn’t remember anything from the study’s early days. He joined as a first-grader in Madison Elementary School in 1970, and didn’t really become aware he was part of a study until middle school.

“I don’t know how I got involved in it at first, but I always believed in the program,” he says. “I wanted to continue participating as an adult because I wanted to keep up on my health and see how I was progressing as I got older. It helped me to monitor my health.”

His wife, Susanna, also started participating in the study in 1970 as a first grader at McKinley Elementary School. She doesn’t remember much about the tests in the early days, either. She’s kept with the study through the years because the relative inconvenience is far outweighed by the discoveries about heart disease.

“It’s important to help other people, so more people know about good heart health,” she says. Susanna and Matthew have always been active and later coached youth sports. Now working as teachers in Muscatine schools, they’re concerned by the increasingly sedentary lives their students lead and what impact that will have on their health later in their life.

“There seems to be a lot of kids who are hurting, and that will lead to a lot of health problems as they grow up,” Matthew says.

For his part, Chamberlin, 64, has had a long career at Hon Industries in Muscatine with a side gig as a musician. He says the study made him more aware of his heart health as he got older. He says he’s glad to have been a part of a project that has helped more people learn about the importance of good heart health.

“It’s helped people become alert to their health issues and shows them they can change their own behavior to improve their health,” he says. “I’d do it again in a minute.”