Sleuths on the trail of cystic fibrosis

Sleuths on the trail of cystic fibrosis

Three decades of delving into the mysteries of cystic fibrosis (CF) began with simple, fundamental curiosity. “I just wanted to understand how the airway worked,” says University of Iowa pulmonologist Michael Welsh, MD.

In particular, he wanted to know how salt ions move across airways—a biological process that helps lungs defend against infection or damage from inhaled pathogens and particles. Knowing that CF increases susceptibility to lung infection, Welsh suspected that abnormal ion transport could play a role in CF disease.

View a timeline of important CF milestones and discoveries made at the University of Iowa and beyond.

Daughter helped by drugs tested on mother's lung tissue

Daughter helped by drugs tested on mother's lung tissue

Johnna Allison’s experience with cystic fibrosis (CF) has been dramatically different from her mother’s, beginning with the diagnosis. Allison was 43 when her CF was confirmed in 2008. Her mother was 10 when she and three siblings were diagnosed. “The doctors pretty much told [my grandparents] to take them home and love them because they would not live very long,” recalls Allison, of Rock Island, Illinois.

But her mother, Catherine “Kay” VanThournout, was a unique case who defied the odds and forecast the possibilities of living longer with CF. Through her enthusiastic participation in research studies at the University of Iowa, she also played a key role in the advances that have improved outcomes for many current CF patients—including her own daughter.

Move aside, mouse model, and bring on the pig

Move aside, mouse model, and bring on the pig

“It’s a pig!”

That was the birth announcement Michael Welsh, MD, emailed colleagues Feb. 27, 2008, marking the successful conclusion of a five-year mission to produce a unique animal model of cystic fibrosis (CF) and open a new chapter in CF research at the University of Iowa.

Mice are the ubiquitous animal model system for medical research, but mice with CF don’t get lung disease. It’s a mystery that has vexed researchers and hampered progress in the three decades since the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene was discovered.

CF effects on the body

CF effects on the body

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a life-shortening, inherited condition that affects about 30,000 Americans and about 70,000 people worldwide. CF gene mutations disrupt the function of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, which controls the movement of chloride and bicarbonate ions across epithelial membranes. CF causes bodily secretions to become thick and sticky, interfering with the function of many organs and systems in the human body.

Gene therapy gets another look

Gene therapy gets another look

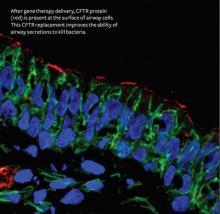

Using gene therapy to treat cystic fibrosis

A few years after the cystic fibrosis (CF) gene was discovered, University of Iowa scientists were the first to report that gene therapy could partially correct the CF ion channel defect in people.

The UI experiments involved nasal delivery of a modified adenovirus vector carrying the corrected cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. Although initial results were promising, it was soon apparent that with each dose, the patient gradually developed immunity to the virus, making it ineffective for long-term therapy.

Featured in Medicine Iowa Spring 2018

You're reading one of the features included in the Spring 2018 issue of Medicine Iowa. Read more news and features about the people and programs focused on teaching, healing, and research in the UI Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine.