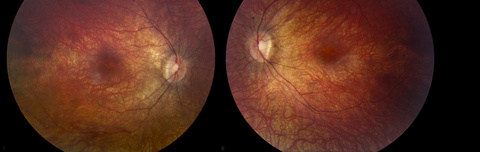

Image from a dilated fundus exam of a patient with Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), an inherited disorder that progressively leads to blindness. According to the exam findings, both optic nerves appeared relatively pink with an intact neuroretinal rim and a cup/disc ratio of 0.3. There was a staphylomatous appearance to the macula in both eyes. Punctate yellow dots and associated pigment mottling were present in the macula and extended into the periphery of both eyes. The vessels were of normal caliber in both eyes.

A gene therapy proven to improve vision and function for children and adults with a rare inherited blinding eye disease was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Dec. 19, making it the first such treatment approved in the United States for an inherited disease and the first in which a new, corrective gene is injected directly into a patient.

Stephen R. Russell, MD, is the service director of vitreoretinal diseases and surgery and holds the Dina J. Schrage Professorship in Macular Degeneration Research in the Institute for Vision Research at the University of Iowa. Russell worked with Al Maguire, MD, Jean Bennett, MD, PhD, Kathy High, MD, and colleagues from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and representatives from Spark Therapeutics in creating the gene therapy that treats certain rare inherited eye disorders that cause blindness. Patients involved in a 2013 clinical trial have maintained improved vision for more than three years.

“All of us in the field of inherited retinal diseases were pleased that the FDA has approved this therapy. While not a cure, the benefits are undeniable and the risks are manageable. We have yet to see a falloff in effect so far,” Russell says.

The therapy, known as Luxturna™ and created by Spark Therapeutics, significantly improves eyesight in patients with a retinal, degenerative disease known as Leber congenital amaurosis, or LCA. LCA is often caused by the mutated gene RPE65. Patients with RPE65 mutations have severe visual impairment from infancy or early childhood that eventually progresses to total blindness in mid-life. About 1,000 to 2,000 people in the United States are affected by LCA.

The new therapy involves injecting copies of a normal version of the RPE65 gene—the gene responsible for producing a protein that makes light receptors work—into the patient’s eye. In the final stages of the 2013 clinical trial, patients were directed by arrows through a mobility course in seven different light levels, with the course changing with each change in lighting. The lowest level of light was that of a moonless summer night, and the brightest was that of a well-lit office.

After a year, patients who at first could not maneuver the room were getting through the course with significant improvement, Russell says.

An FDA advisory panel unanimously recommended approval of the gene therapy in October of this year.