A study involving University of Iowa Health Care lung imaging experts suggests that common, inheritable variations in lung anatomy might increase the risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

COPD, the third leading cause of death worldwide, is a serious, progressive lung disease that makes it hard to breathe. In the United States, an estimated 16 million people are diagnosed with COPD, and it is likely that millions more have the condition. While smoking is a major risk factor for COPD, there is a lack of understanding about other factors that also increase the risk of developing the disease.

UI oversaw imaging for the study

The new study examined X-ray computed tomography (CT) lung scans from 5,054 people and found that one in four study participants had airway anatomy that differed from standard airway branching patterns. The study also found these common variations in lung anatomy had health consequences related to the participants’ susceptibility to COPD.

A UI team, led by Eric Hoffman, PhD, headed the radiology portion of the research. The team developed imaging protocols, oversaw imaging and quality control, and provided the quantitative analysis of the images via a UI-derived company, VIDA Diagnostics. Researchers at Columbia University combined the UI data on lung anatomy and function with other clinical and demographic data associated with each participant. The results of the study were published in the Early Edition of PNAS the week of Jan. 15.

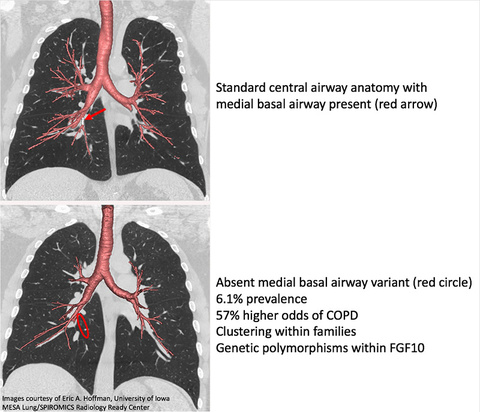

Images above: CT scans of lungs show inherited differences in lung anatomy that are linked to increased risk of developing COPD. The upper panel shows standard central airway anatomy. The red arrow highlights the presence of the medial basal airway branch. The lower panel shows “Variant 1” lung anatomy where the medial basal airway branch is missing (red circle). The study shows that 6.1 percent of study participants had variant 1, which was associated with an increased risk of developing COPD (57 percent higher odds). Credit: Eric A. Hoffman, University of Iowa, MESA Lung/SPIROMICS Radiology Ready Center

Focus on two anatomic variations

The lung anatomy variations fell into two types when compared with standard airway anatomy: Variant 1, present in 6.1 percent of the participants, is missing a branch in the right lower lobe of the lung, and variant 2, present in 16 percent of participants, has an added branch in the right lower lobe.

Participants with variant 1 type anatomy who were also smokers were 1.78 times more likely to have COPD compared with smokers who have standard airway configuration. A greater percentage of people with variant 1 also showed symptoms of dyspnea (shortness of breath). Participants with variant 2 were 1.4 times more likely to have COPD regardless of whether they smoke or not, and this variant also is associated with chronic bronchitis (airway inflammation). Individuals with variant 2 also have a greater percentage of emphysema throughout the lung, not just in the right lower lobe.

A potential key to COPD susceptibility

“We think that these variations in airway anatomy, a missing branch in one case and an added branch in the other, do not directly cause disease susceptibility and respiratory symptoms, but rather that this alteration in airway anatomy is a sign of a more globally altered lung anatomy that affects a person’s susceptibility to lung disease,” says Hoffman, UI professor of radiology, internal medicine, and biomedical engineering, and an author on the study. “The findings suggest that these easily detectable anatomical variations might represent inherited biomarkers that could potentially help identify people who are at risk for COPD.”

The study also revealed these anatomical variations have a strong familial association. Almost one third (31 percent) of siblings of a person with variant 1 also had that type of lung anatomy, and almost half (46 percent) of siblings of a person with variant 2 also had that variation.

A genetic assessment of these subjects demonstrated that variant 1 is associated with a gene location controlling fibroblast growth factor 10, which is associated with development of the lung airway branching pattern in the womb.

Combination of genetics and environment

The new findings suggest that the interplay between genetic factors and environmental factors, such as smoking, that influence lung development may be important for a person’s risk of developing COPD. The researchers note, however, that even in light of the new findings, quitting smoking remains the best way of preventing COPD.

The lead researchers on the study were Benjamin Smith and R. Graham Barr at Columbia University. Hoffman directs the Advanced Pulmonary Physiomic Imaging Laboratory (APPIL), the UI-based imaging center for numerous large multi-center studies focused on lung disease and asthma. Sponsored by the National Heart and Lung Institute of the National Institutes of Health, two of these studies, MESA Lung and SPIROMICS, were involved in the current study.