Could healthy gut bacteria hold the key to a new way of treating multiple sclerosis? That is a possibility raised by a new study in mice conducted by scientists with University of Iowa Health Care and Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The study, published Aug. 8 in the journal Cell Reports, found that a human gut bacterium, Prevotella histicola, suppresses multiple sclerosis symptoms in a mouse model of this immune-related disease. The bacteria appear to produce their beneficial effect by influencing the levels and function of particular immune system cells that are involved in controlling inflammation.

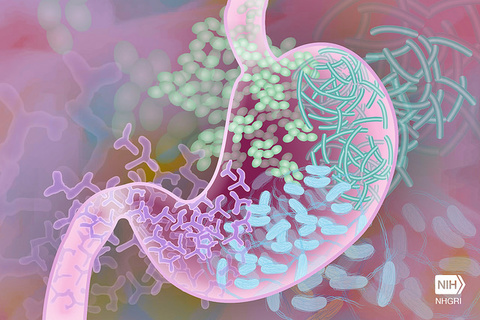

“We each have trillions of bacteria in our gut that play a critical role in keeping us healthy, and we believe that the gut microbiota is an untapped source for development of the next generation of drugs,” says Ashutosh Mangalam, PhD, UI assistant professor of pathology and lead study author. “In that regard, we are excited that bacteria discovered by our groups might have the potential to be used as individual or combination therapies for treatment of MS. However, we need to conduct many more studies before we can take bacteria-based therapy to clinical trials.”

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disabling disease that targets the central nervous system, disrupting nerve signals between the brain and the rest of the body. MS can cause a variety of health problems, including muscle weakness, impaired balance and coordination, and problems with vision and thinking. The disease is unpredictable and can vary in its severity and how fast it progresses. There are several treatments that slow down or control MS, but there is currently no cure.

Previously, the team had shown that patients with MS have a distinct gut microbiome compared to healthy controls. In particular, patients with MS had lower levels of certain bacteria, including Prevotella.

In the new study, mouse models of MS treated with P. histicola (cultured from the human intestine) had less inflammation overall and less destruction of the myelin sheath that protects nerve fibers than untreated mice. The researcher also found that P. histicola caused a decrease in two types of pro-inflammatory cells, while increasing families of cells that induce tolerance: regulatory T cells, tolerogenic dendritic cells and a type of macrophage, all disease-fighting factors.

“Our research suggests that Prevotella has the ability to promote special kinds of immune cells, which can suppress disease-causing cells in MS,” Mangalam explains. “We think Prevotella boost our body’s defense system by promoting immune cells responsible for keeping other MS-causing immune reactions in check.”

The research was funded by the Department of Defense and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

In addition to Mangalam and Murray, the research team included Shailesh Shahi, Ramakrishna Sompallae, and Katherine Gibson-Corely, at the UI, and David Luckey, Melissa Karau, Erick Marietta, Ningling Luo, Rok Seon Choung, Josephine Ju, Robin Patel, Moses Rodriguez, Chella David, and Veena Taneja, of Mayo Clinic.