A new discovery showing that measles virus hitches a ride inside a protective raft of airway cells when it leaves a host, may help explain why this virus is so highly contagious.

The new finding from the University of Iowa lab of Patrick Sinn, PhD, shows that patches of measles-infected airway cells containing large quantities of virus dislodge from the airway surface. These aerosolized rafts of cells appear to be viable and may protect the measle virus, allowing it to survive for longer outside of the body. The study also shows that the measles virus inside these cells is able to infect human cells.

“We‘ve known for a long time that measles is airborne and can survive for several hours after it has been coughed or sneezed out,” says Sinn, a professor of pediatrics-pulmonary disease in the UI Stead Family Department of Pediatrics. “Our discovery that infectious measles virus is contained and possibly protected inside these patches of viable cells could represent a whole new paradigm for how measles can spread so efficiently from person to person and could help explain why measles is the most contagious human disease.”

Understanding the strategies viruses use to maximize transmissibility is important for developing effective ways to prevent infection and reduce the spread of disease.

One measure of a disease’s infectiousness is the reproductive number, or R0 number, which is the average number of people infected by one sick person. With COVID-19, for example, the original SARS COV-2 virus had an R0 of around three, meaning one infected person was likely to infect three more people. The delta variant, which is now the predominant version of the virus, is much more infectious. Delta has an R0 of around 7. Measles is the most infectious human virus known and has an R0 of 18. The cause of this extreme infectiousness has been a mystery.

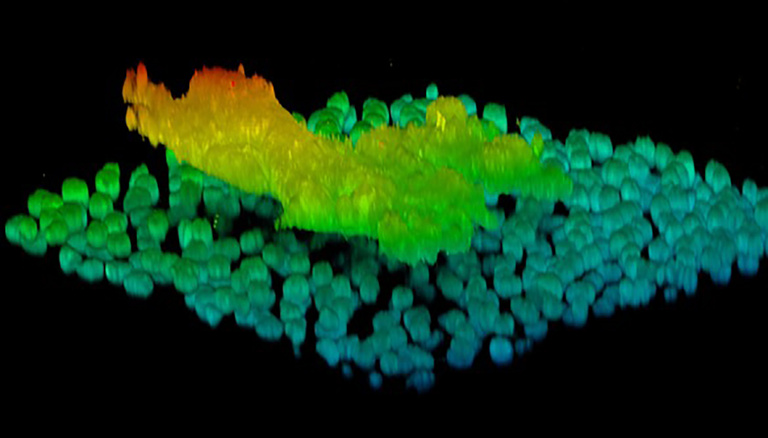

The new UI study, published recently in PLOS Pathogens, suggests that measles employs a unique tactic to exit from the infected person and infect new hosts. Sinn’s team have previously shown that once the virus enters cells in the epithelium layer of the airway, it rapidly spreads laterally from cell to cell creating patches of infected cells that Sinn calls infectious centers. The new study uses confocal microscopy to show that these infectious centers peel away from the airway carrying large doses of infectious measles virus.

“This unique strategy could contribute to measles strikingly high reproductive number by allowing the virus to survive longer in the environment and by delivering a high infectious dose to the next host,” say Sinn, who also is a UI professor of microbiology and immunology.

In addition to Sinn, the research team included Camilla Hippee, a UI graduate student in microbiology and immunology, and Brajesh Singh, PhD, an associate research scientist in Sinn’s lab, who were co-lead authors, as well as Andrew Thurman, Ashley Cooney, and Alejandro Pezzulo with UI Health Care, and Roberto Cattaneo at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The research was funded in part by grants from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases.