Saving neurons may offer new approach for treating Alzheimer’s disease

A soon-to-be-published study by researchers from the Iowa Neuroscience Institute indicates that protecting nerve cells with a specific compound helps prevent memory and learning problems in lab animals.

Senior study author Andrew Pieper, MD, PhD, and first author Jaymie Voorhees, PhD, have found that treatment with a neuroprotective compound that saves brain cells from dying also prevents the development of depression-like behavior and the later onset of memory and learning problems in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease.

Although the treatment protects the animals from Alzheimer’s-type symptoms, it does not alter the buildup of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the rat brains.

“We have known for a long time that the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease have amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles of abnormal tau protein, but it isn’t completely understood what is cause or effect in the disease process,” says Pieper, professor of psychiatry in the UI Carver College of Medicine and associate director of the Iowa Neuroscience Institute at the University of Iowa.

“Our study shows that keeping neurons alive in the brain helps animals maintain normal neurologic function, regardless of earlier pathological events in the disease, such as accumulation of amyloid plaque and tau tangles,” he says.

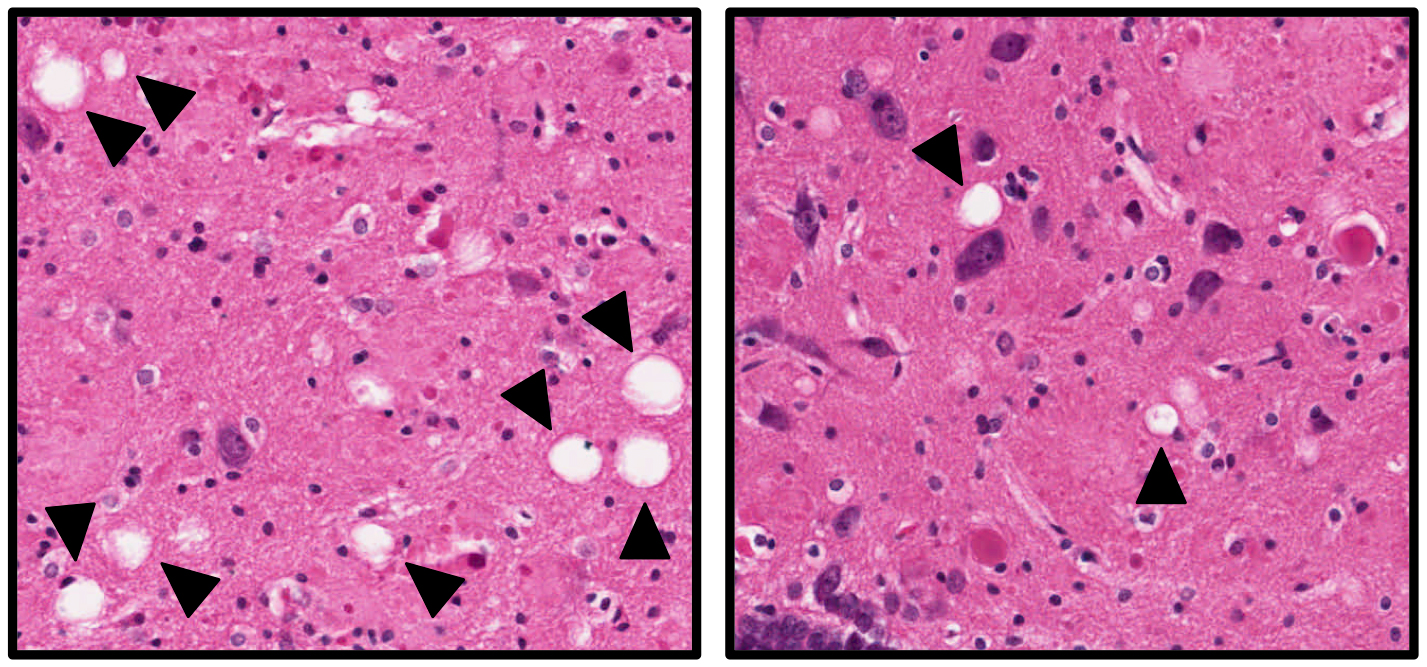

The images show brain tissue from Alzheimer's rats that were untreated (left) or treated (right) with the neuroprotective compound. The white "holes" indicated by the arrows are areas of brain cell death, and are more numerous in the untreated rats. Although the treatment protects the animals from neuronal cell death and Alzheimer’s-type symptoms, it does not alter the buildup of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the rat brains.

The impact of Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating neurodegenerative condition that gradually erodes a person’s memory and cognitive abilities. Estimates suggest that more than 5 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease and it is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, according to the National Institute on Aging.

In addition to the impact on cognition and memory, Alzheimer’s disease also can affect mood, with many people experiencing depression and anxiety before the cognitive decline is apparent. People who develop depression for the first time late in life are at a significantly increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

“Traditional therapies have targeted the characteristic lesions in Alzheimer's disease, amyloid deposition, and tau pathologies," says Voorhees, first author of the study, which is an article-in-press in Biological Psychiatry. “The findings of this study show that simply protecting neurons in Alzheimer's disease without addressing the earlier pathological events may have potential as a new and exciting therapy.”

A compound to protect brain cells

Pieper and Voorhees used an experimental compound called P7C3-S243 to prevent brain cells from dying in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease.

The original P7C3 compound was discovered by Pieper and colleagues almost a decade ago, and P7C3-based compounds have since been shown to protect newborn neurons and mature neurons from cell death in animal models of many neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), stroke, and traumatic brain injury.

P7C3 compounds also have been shown to protect animals from developing depression-like behavior in response to stress-induced killing of nerve cells in the hippocampus, a brain region critical to mood regulation and cognition.

The researchers tested the P7C3 compound in a well-established rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. As these rats age, they develop learning and memory problems that resemble the cognitive impairment seen in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

The new study, however, revealed another similarity with Alzheimer’s patients. By 15 months of age, before the onset of memory problems, the rats developed depression-like symptoms. Developing depression for the first time late in life is associated with a significantly increased risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease, but this symptom has not been previously seen in animal models of the disease.

The study’s approach

Over a three-year period, Voorhees tested a large number of male and female Alzheimer’s and wild type rats that were divided into two groups. One group received the P7C3 compound on a daily basis starting at six months of age, and the other group received a placebo. The rats were tested at 15 months and 24 months of age for depressive-type behavior and learning and memory abilities.

At 15 months of age, all the rats—both Alzheimer’s model and wild type, treated and untreated—had normal learning and memory abilities. However, the untreated Alzheimer’s rats exhibited pronounced depression-type behavior, while the Alzheimer’s rats that had been treated with the neuroprotective P7C3 compound behaved like the control rats and did not show depressive-type behavior.

At 24 months of age (very old for rats), untreated Alzheimer’s rats had learning and memory deficits compared to control rats. In contrast, the P7C3-treated Alzheimer’s rats were protected and had similar cognitive abilities to the control rats.

The team also examined the brains of the rats at the 15-month and 24-month time points. They found the traditional hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease—amyloid plaques, tau tangles, and neuroinflammation—were dramatically increased in the Alzheimer’s rats regardless of whether they were treated with P7C3 or not. However, significantly more neurons survived in the brains of Alzheimer’s rats that had received the P7C3 treatment.

“This suggests a potential clinical benefit from keeping the brain cells alive even in the presence of earlier pathological events in Alzheimer’s disease, such as amyloid accumulation, tau tangles, and neuroinflammation,” Pieper says. “In cases of new-onset late-life depression, a treatment like P7C3 might be particularly useful as it could help stabilize mood and also protect from later memory problems in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.”

Members of the research team

In addition to Pieper and Voorhees, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at St. Louis University, the research team included University of Iowa researchers Matthew Remy, Coral Cintrón-Pérez, Eli El Rassi, Michael Kahn, Laura Dutca, Terry Yin, and Latisha McDaniel. Noelle Williams at University of Texas Southwestern and Daniel Brat at Emory University were also part of the team.

Pieper notes that the study received critical funding from philanthropic organizations: the Mary Alice Smith Fund for Neuropsychiatry Research, the Titan Neurology Research Fund, and the Brockman Medical Research Foundation.

This work was also supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences through the University of Iowa Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (P30 ES005605), and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Pieper is co-founder and consultant of Neuroprotective Therapeutics, and holds patents related to the P7C3 series of neuroprotective compounds.

The Iowa Neuroscience Institute builds on the university’s decades-long tradition as a leading center for the study of neuroscience, promoting interdisciplinary collaboration and supporting innovation in foundational, translational, and clinical research.