See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information may be more applicable.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Music Making and Hearing Loss:

Information for Audiologists

Audiologists play an important role in protecting the hearing of musicians by providing hearing screenings, testing, outreach programs, protection device fittings, and counseling on healthy hearing habits specifically for musicians. The information on this page can help you understand more fully factors that contribute to music-induced hearing loss (MIHL) and challenges that musicians face in establishing hearing-healthy habits and using hearing protection. This page includes:

-

Music Basics

-

Musical Environments

-

Hearing Protection for Musicians

-

Musician Examples

-

Musician Help Seeking Behaviors

1, 2

Music Basics

Music spaces are often loud, and music sound levels can change rapidly and vary greatly, even within the same song (from 70 dB to 120 dB!). In addition, because practice makes perfect, musicians are likely to spend many hours practicing as well as performing their craft. Prior studies show that many musicians indeed are at risk for hearing loss. Hearing loss resulting from too much exposure to loud music is called Music-Induced Hearing Loss (MIHL). Consider the following.

Musicians and Hearing Problems:

-

Close to half of musicians have experienced hearing loss symptoms (Greasley et al., 2020).

-

Musicians are affected differently by hearing loss than most non-musicians.

-

Musicians’ livelihoods are based on their ability to hear.

-

Pitch discrimination, rhythmic timing, timbre detection, and loudness are all perceptions that may change with hearing loss.

-

These changes can affect job performance and put musicians at risk for job loss and decreased quality of life.

-

-

Musicians often don’t realize their risk for hearing loss until they experience hearing damage.

-

The most common hearing problems are (Greasley et al., 2020):

-

Tinnitus (younger musicians)

-

Hyperacusis (older musicians)

-

Bilateral hearing loss (older musicians)

-

-

-

Musician circumstances and needs vary from one musician to the next.

-

Musicians may not be able to make accurate judgments regarding whether the music they are creating or listening to is at a safe level (Hagerman, 2013).

-

Musicians sometimes think over-the-counter foam earplugs are the only option for protecting their hearing, but those inexpensive earplugs often decrease the quality of the music. Other strategies should be explored as well.

- Educational programs and an attitudinal shift towards hearing preservation may help change the culture towards hearings protection and healthy-hearing practices in music settings.

Audiologists can play a key role in educating musicians and providing effective healthy-hearing options that maintain quality musical experiences.

Musical Environments

Environments in which musicians find themselves vary greatly in terms of sound levels and the risk they pose for permanent hearing loss. Being informed about risk factors in one’s ensemble can help prevent music-induced hearing disorders and their impact on musicians’ careers and lives. Audiologists can help musicians understand the facts and which environments put them at risk for hearing loss.

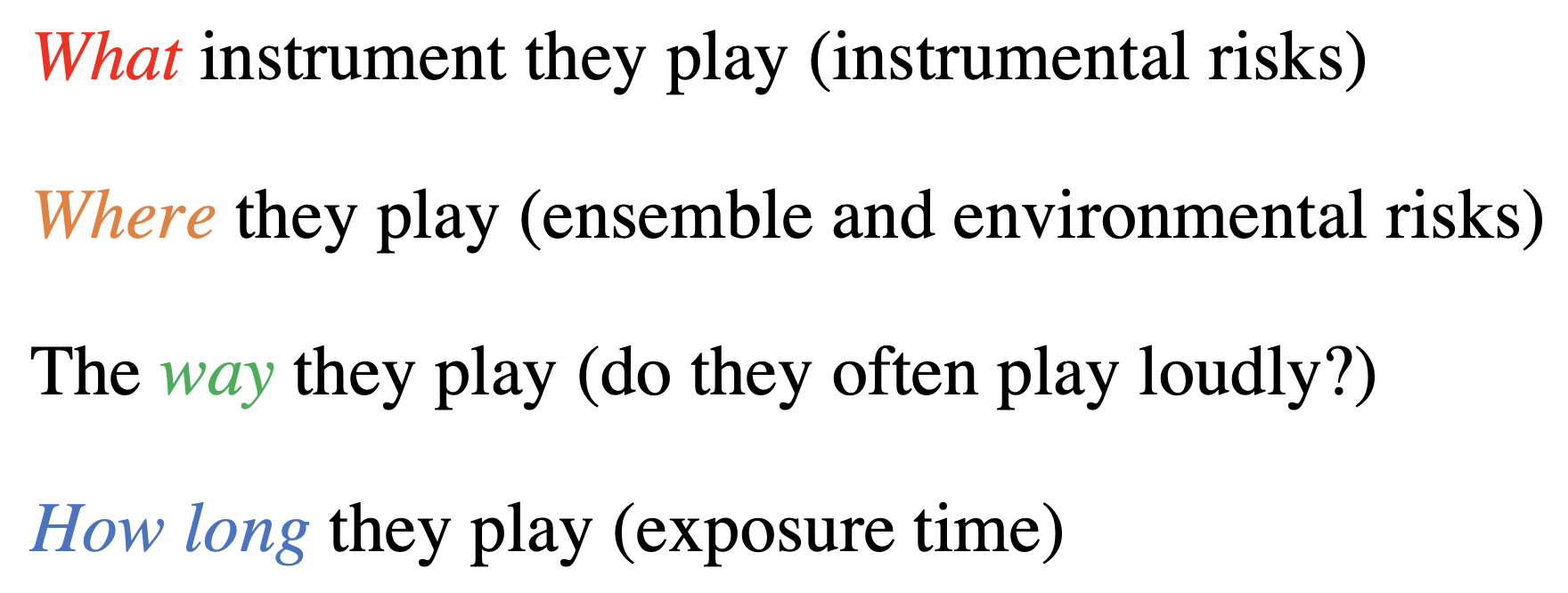

Four Factors of Music-Induced Hearing Loss (MIHL)

-

There are four general factors for musicians to consider regarding their risk of MIHL. These are:

-

What instrument they play (instrumental risks)

-

Where they play (ensemble and environmental risks)

-

The way they play (do they often play loudly?)

-

How long they play (exposure time)

-

Instrument Risks:

-

Some instruments are inherently louder than others. Playing those instruments or sitting near them can increase one’s risk of hearing loss.

-

Percussion, brass, woodwinds, and any electronically amplified instruments are inherently louder and can put the musician at risk.

-

While instruments can all be played on a continuum of very quiet to very loud, some instruments can be played more loudly than others. This chart lists the maximum values of various instruments' peak sound levels (Healthy Hearing, 2013; Etymotic Research, n.d.; Eastern Kentucky University, n.d.):

| Instrument | Peak Sound Level in dB SPL |

| Piccolo | 102-122 dB |

| Flute | 100-112 dB |

| Oboe | 90-102 dB |

| Clarinet | 93-119 dB |

| Saxophone | 90-113 dB |

| Trumpet | 109-120 dB |

| French Horn | 90-106 dB |

| Trombone | 85-114 dB |

| Euphonium | 96-113 dB |

| Tuba | 110-117 dB |

| Violin | 82-105 dB |

| Viola | 82-105 dB |

| Cello | 85-111 dB |

| Double Bass | 85-89 dB |

| Piano | 84-103 dB |

| Percussion | 102-122 dB |

| Vocalist | 70 dB |

Ensemble Risks:

-

Musicians who play in some types of ensembles may be at higher risk of hearing damage. The following ensembles are general examples in order of hearing loss risk (from highest to lowest risk):

-

Marching bands/drum corps

-

Jazz/pop/rock bands

-

Wind ensembles

-

Symphonic orchestras

-

Large choir

-

String quartet

-

Small choir

-

-

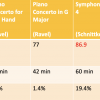

Classical music can be just as loud as rock music depending on the piece and the specific passage, as seen below.

Environmental Risks:

-

Reverberant environments create a higher sound dosage than typical music practice rooms or anechoic settings This is especially problematic in average elementary and high school settings with linoleum floors and walls. These are highly reverberant and add to sound levels.

-

Music-making environments should have fabric-wrapped panels and acoustic foam to absorb sounds

-

Carpet and drapes can help reduce reverberation and overall sound levels

-

Musicians with bell instruments (brass, saxophones) should keep their bell above or to the side of their stands to reduce reflected sounds (see photo below)

-

-

Ensemble placement can increase or decrease a musician’s risk of hearing loss. Musicians closer to louder instruments, or walls or stands that reflect sound, are at a higher risk of hearing loss than those farther from loud instruments or near the edge of the ensemble.

-

Large ensembles should use risers so instruments such as trumpets and trombones play above (not at) the heads of those in front of them. However, risers alone are not sufficient (see photo below). Only one trumpet player is playing above the trombonists' heads. Musicians should be reminded to play above the heads of those in front of them.

-

Cumulative Risks:

-

Genetics: Some people are genetically at greater risk for noise-induced hearing damage.

-

On-going exposure to loud music: Daily, weekly, yearly exposure

-

Multiple temporary threshold shifts or temporary hearing loss experiences [Click here for more information about temporary threshold shifts.]

-

Engaging in loud activities outside of the musical experiences (loud machinery, motorcycles, lawn mowers, concerts, clubs, etc.)

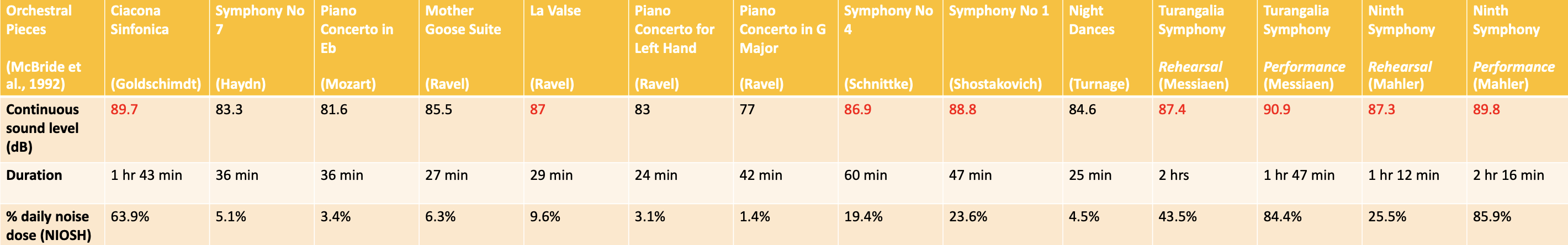

Hearing Protection for Musicians

-

Foam earplugs: These are the most affordable option, but often not preferred because they muffle the sound and decrease perceived musical fidelity.

-

Non-custom professional and recreational ER high-fidelity earplugs (9, 15, 20, or 25 dB): These reduce all sound levels equally without greatly affecting pitch, resolution, balance, or sound quality. These are often the preferred hearing protection for musicians.

-

Customized hearing protection: These earplugs cost more but are specifically designed for the individual. These are generally regarded as the most comfortable and safest option for hearing protection.

-

In-ear monitors for musicians are NOT hearing protection. Some studies have shown that the preferred setting used by musicians for in-ear monitors was only -0.6 dB different than the floor monitors. However, the musicians agreed to reduced sound levels up to -6dB, so in-ear monitors may be effective if sound levels are carefully watched and reduced.

-

Fitting hearing protection is similar to fitting hearing aids. Music does not sound the same through hearing protection, so remind your patients that it takes some time to adjust to the new sound. Encourage them to talk to other musicians who use hearing protection successfully.

-

It's not all or nothing!

-

Remind your musicians that reducing the sound level by 3 dB can halve the sound exposure. They can also wear hearing protection when commuting and during warm-ups, or use one plug at a time during individual practice or rehearsals, and/or when playing long tones.

-

Not all hearing protection is created equal. Customized hearing protection is the best form of hearing protection, but even using ER-9s can help reduce dB level while still preserving musical nuances.

-

Musician Examples:

Musician Help Seeking Behaviors (Greasley et al., 2020)

| Worry Most about Sound Exposure | Most Likely to Report Hearing Loss | Most Likely to Seek Help |

| Orchestral musicians | Guitar players | Singers |

| Brass players | Brass players | Pianists |

| Strings | Band members | Strings |

| Percussionists | Percussionists | Brass players |

| Woodwinds | ||

| Music teachers | ||

| Gig/freelance instrumentalists | ||

| Singers | ||

| Pianists |

| Main Motivations for Wearing Hearing Protection |

| Loud music |

| Tinnitus |

| Play brass, percussion, guitar, or piccolo |

| Advice or awareness from job/university |

| Pain/hyperacusis |

| Fear, worry, or concern over hearing loss |

| To prevent further damage |

| Bad acoustics |

| Job/university provided protection |

Click the link below to learn more about music-induced hearing loss (MIHL):

Music-Induced Hearing Loss: Loud Concerts, Musicians and Hearing Loss Information for Audiologists

References

Behar, A., MacDonald, E., Lee, J., Cui, J., Kunov, H., & Wong, W. (2004). Noise exposure of music teachers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 4, 243‐247.

Etymotic Research. (n.d.). Noise-Induced Hearing Loss: Know the Risk. Retrieved August 04, 2020, from https://www.etymotic.com/downloads/dl/file/id/632/product/307/noise_indu...

Eastern Kentucky University Health and Safety - Hearing. (n.d.). Retrieved August 04, 2020, from https://music.eku.edu/sites/music.eku.edu/files/ekuhealthandsafety.pdf

Fligor, B. J., & Cox, C. L. (2004). Output level of commercially available portable compact disc players and the potential risk to hearing. Ear and Hearing, 25, 513–527. doi:10.1097/00003446-200412000-00001

Gopal, K., Chesky, K., Beschoner, E., Nelson, P., & Stewart, B. (2013). Auditory risk assessment of college music students in jazz band-based instructional activity. Noise and Health, 15(65), 246-252.

Greasley, A.E., Fulford, R.J., Pickard, M., & Hamilton, N. (2020). Help Musicians UK hearing survey: Musicians’ hearing and hearing protection. Psychology of Music, 48(4), 529-546.

Hagerman, B. (2013). Musicians' ability to judge the risk of acquiring noise induced hearing loss. Noise & Health, 15(64), 199-203. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/10.4103/1463-1741.112376

Healthy Hearing. (2013, October 09). Which musicians are at high risk for hearing loss? Retrieved August 05, 2020, from https://www.healthyhearing.com/report/51549-Which-musicians-are-most-at-...

Hodges, D. (2009). Brains and Music, Whales and Apes, Hearing and Learning . . . and More. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 27(2), 62-75.

Hoover, A., & Krishnamurti, S. (2010). Survey of college students’ MP3 listening: Habits, safety issues, attitudes, and education. American Journal of Audiology, 19(1), 73–83. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2010/08-0036)

Kahari, K.R., Zachau, G., Eklof, M., et al. (2003). Assessment of hearing and hearing disorders in rock/jazz musicians. International Journal of Audiology, 42, 279-288.

Kujawa, S. G., & Liberman, M. C. (2009). Adding insult to injury: Cochlear nerve degeneration after "temporary" noise-induced hearing loss. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(45), 14077–14085. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2845-09.2009

Levey, S., Levey, T., & Fligor, B. J. (2011). Noise exposure estimates of urban MP3 player users. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54(1), 263–277. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0283)

Liberman, M.C., & Kujawa, S.G. (2017). Cochlear synaptopathy in acquired sensorineural hearing loss: Manifestations and mechanisms. Hearing Research, 349, 138-147.

McBride, D., Gill, F., Proops, D., Harrington, M., Gardiner, K., & Attwell, C. (1992). Noise and the classical musician. British Medical Journal, 305 (6868), 1561-1563.

Pawlaczyk-Luszczynska, M., Zamojska-Daniszewska, M., Dudarewicz, A., & Zaborowski, K. (2017). Exposure to excessive sounds and hearing status in academic classical music students. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 30(1), 55-75.

Phillips, S., & Mace, S. (2008). Sound-level measurements in music practice rooms. Music Performance Research, 2, 36–47.

Phillips, S., Shoemaker, J., Mace, S., & Hodges, D. (2008). Environmental factors in susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss in student musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 23, 20–28.

Presley, D. (2007). An analysis of sound-exposures of drum and bugle corps percussionists. Percussion Notes, August, 70–75.

Rideout, V., and Robb, M. B. (2019). The Common Sense census: Media use by tweens and teens, 2019. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media.

Smith, K., Neilsen, T., & Grimshaw, J. (2019). University student musician noise-dosage study measuring both ensemble and full-day noise exposure. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 145(6), EL494.

Walter, J. S. (2009). Sound exposure levels experienced by university wind band members. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 24(2), 63-70. Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.proxy.l...

Walter, J. S., Mace, S. T., & Phillips, S. L. (2008). Preventing Hearing Loss. Published Proceedings from the National Association of Schools of Music 2006 Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois.

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.