See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information may be more similar to your situation.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Music-Induced Hearing Loss: An Introduction

1, 2

Although people may enjoy playing or listening to loud music, extensive exposure to loud music can result in permanent damage to hearing, called music-induced hearing loss. Music-induced hearing loss (MIHL) is common among musicians and avid music listeners. In 2015, the World Health Organization warned that 1.1 billion young people (or about 50%) were at risk of hearing loss due to personal listening devices and music venues in which sounds may reach dangerously loud levels for hours on end. Even though music settings may be just as loud as construction sites, factories, riflery ranges, or lawn mowers, the use of hearing protection is much less common among music listeners and musicians (Olson et al., 2016; Verbeek et al., 2014).

Topics covered on this page include:

This page is designed for recreational and professional musicians and avid music listeners. It describes risk factors and symptoms of music-induced hearing loss.

MIHL Symptoms

Music-Induced Hearing Loss (MIHL):

Music-induced hearing loss is a hearing loss resulting from exposure to high levels of music over prolonged periods of time.

-

There are 5 hearing disorders caused by music-induced hearing loss (Kahari et al., 2003).

-

Hearing loss

-

Total or partial inability to hear sounds. In MIHL, this often, but not always, affects higher frequencies.

-

To hear an example of the loss of high frequencies click on this link.

-

-

Distortion of sound

-

Sounds (such as "s" and "t" consonants) may blur together and lack clarity.

-

To hear an example of hearing loss with lack of clarity click on this link.

-

-

Tinnitus

-

Perception of sound in the absence of it (such as whistling, buzzing or roaring sounds within the ear or head)

-

To hear examples of tinnitus click on this link.

-

-

Hyperacusis

-

Decreased sound tolerance; increased physical discomfort from sounds that are loud, but tolerable to others

-

Can lead to phonophobia - the fear of sound

-

-

Diplacusis

-

Distortion of pitch

-

One pitch may sound like different pitches to each ear or as different pitches in the same ear.

-

Inability to match pitch, or one note being heard as two

-

To hear an example of diplacusis click on this link.

-

-

What puts you at risk for MIHL?

Risk Factors:

-

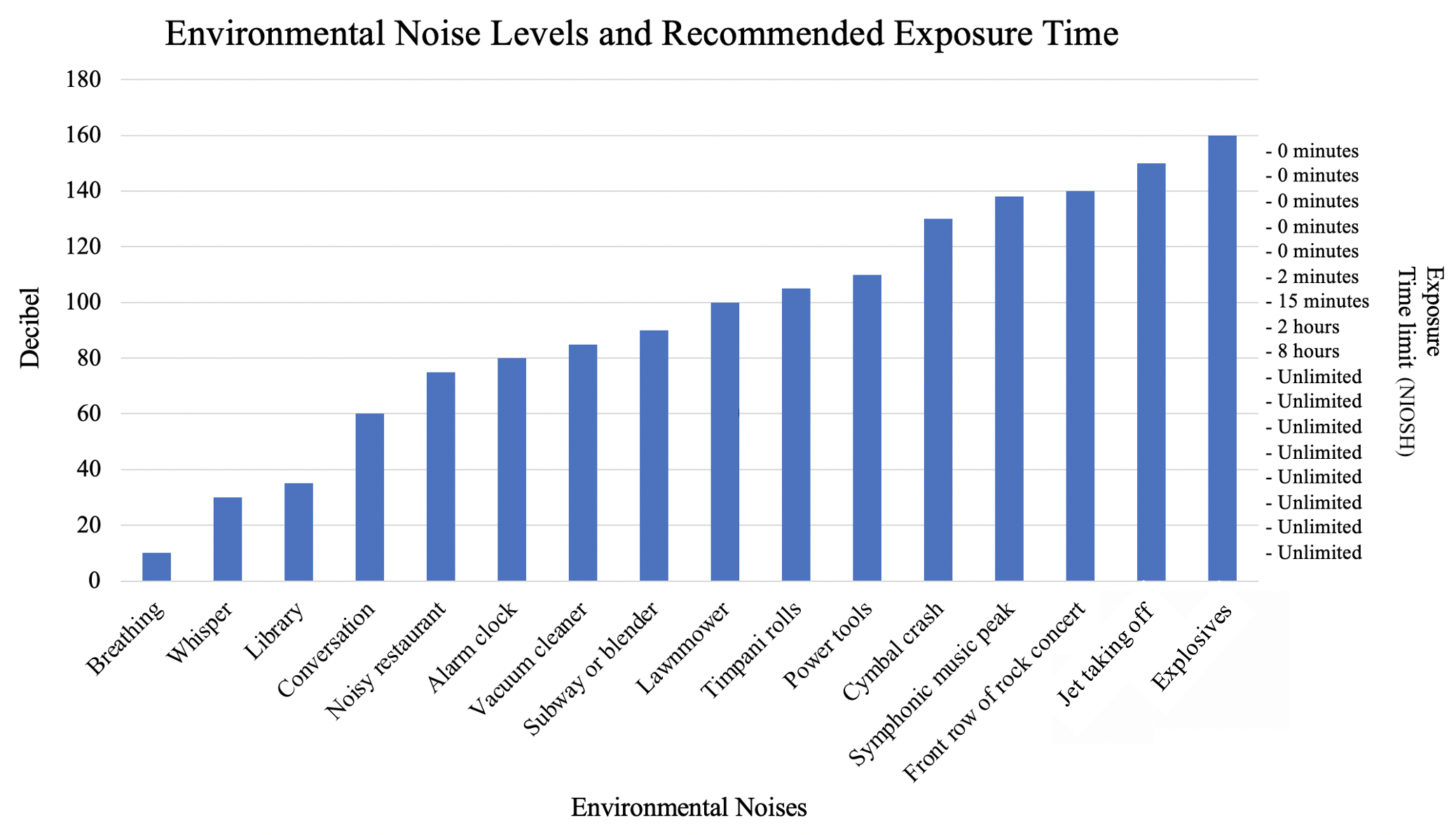

Defining risk is complicated. There are three main organizations that have differing dB levels for safe sound exposure.

-

World Health Organization (WHO)

-

Safe sound for 8 hours/day: 80 dB and below

-

-

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

-

Safe sound for 8 hours/day: 85 dB and below

-

-

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

-

Safe sound for 8 hours/day: 90 dB and below

-

-

While there are small differences in these definitions (exact dB at which sounds are risky), all three organizations acknowledge that prolonged exposure to loud sounds, including music, is harmful to hearing.

-

-

Any sound, even those we enjoy such as music, can cause hearing loss.

-

Repeated exposure to sound 85 dB or louder (the sound of a window AC unit) for 8 hours or more a day can cause premature and permanent hearing loss (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, 2019).

-

Most noise-induced hearing loss happens gradually and painlessly.

-

-

Daily sound dosage is similar to daily salt intake. It is cumulative throughout the day; the right amount is healthy, but too much can be harmful.

-

All experiences during a 24-hour period which expose you to sound must be included. These can be:

-

Sporting events

-

Video games

-

Toys

-

Farming equipment

-

Concerts

-

Personal music players

-

Commuting

-

-

Dose = Intensity + Time

-

How loud a sound is combined with how long you have listened.

-

-

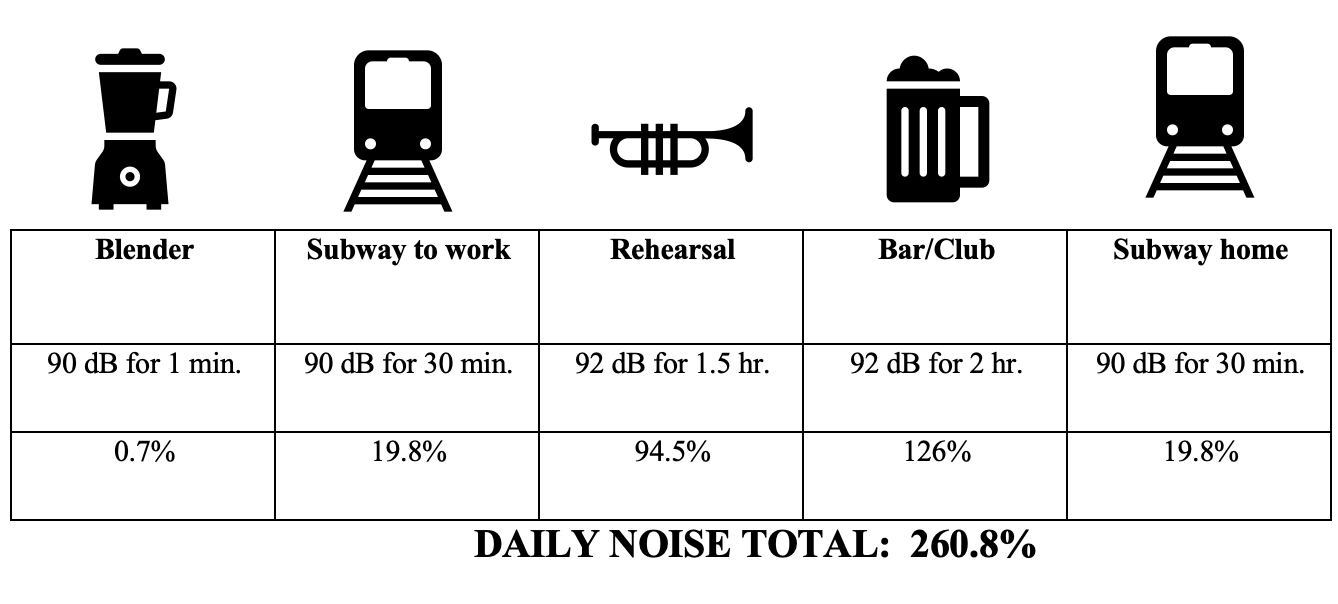

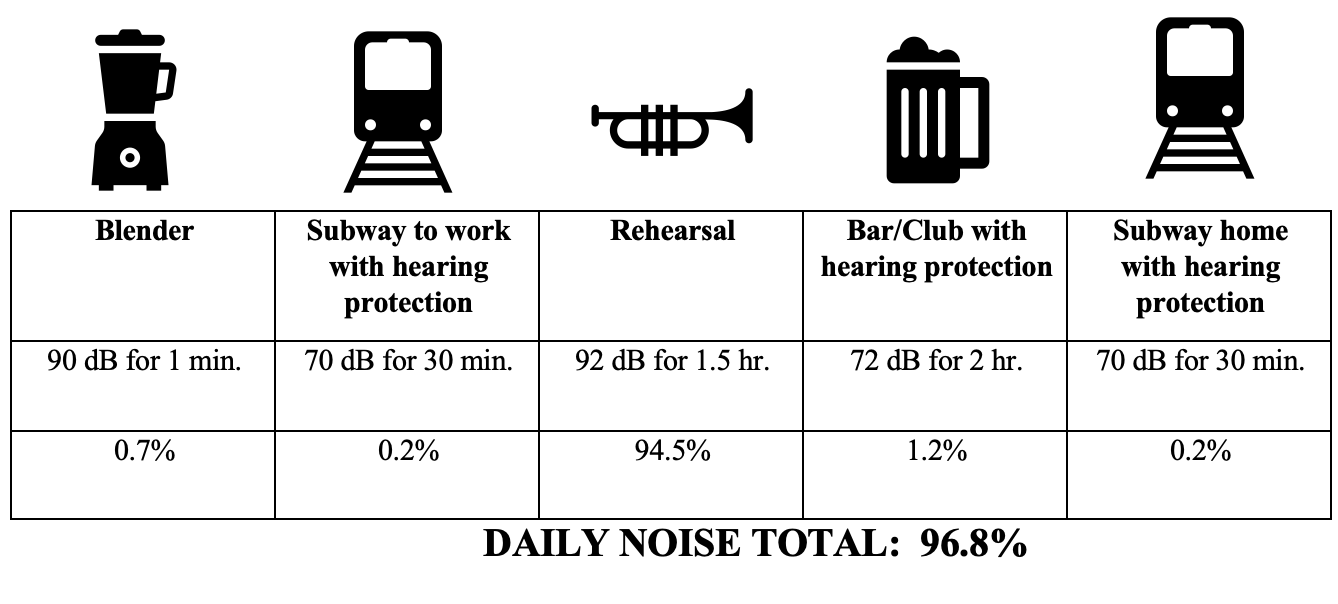

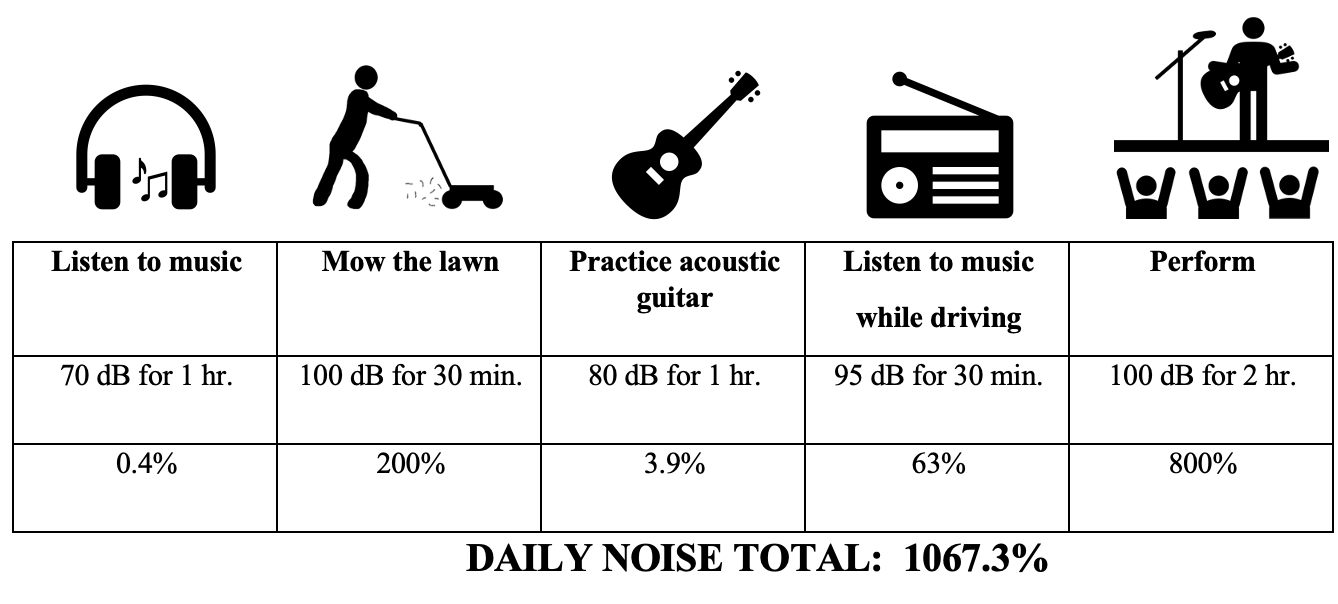

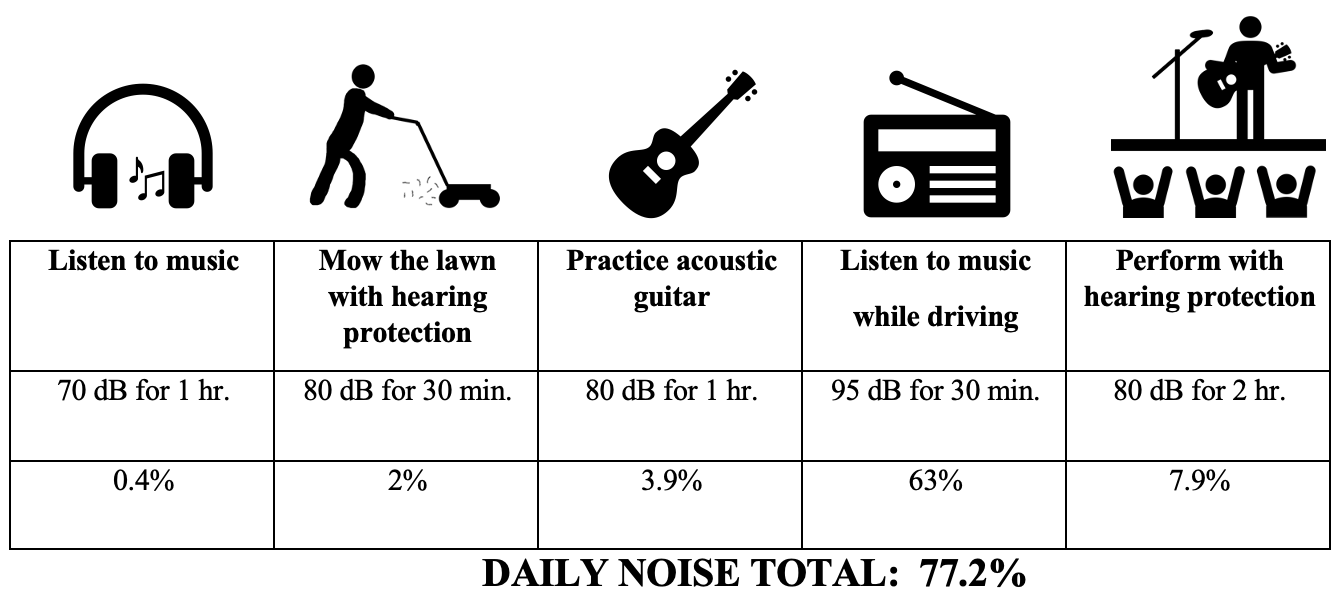

The following are a few examples of daily noise dosage (percentages according to NIOSH guidelines) with and without hearing protection. You can compute your own daily noise exposure on this website.

-

Under the Occupational Noise Regulations select "NIOSH"

-

Using a decibel app on your phone, measure the current volume of your environment

-

Enter in your decibel level in the "Sound Level dB(A)" box

-

Enter your length of time in the environment in the "Exposure Time" boxes

-

Your sound dose results will appear as a percentage of your daily noise allowance

-

-

Music Example without Hearing Protection

Music Example with Hearing Protection

Music Example without Hearing Protection

Music Example with Hearing Protection

You are never too young to protect your hearing!

-

Temporary hearing loss can be dangerous.

-

Temporary Threshold Shifts, or temporary hearing loss, can occur after listening to loud noise or music continuously. After leaving the loud environment (bar, club, concert), you may experience reduced hearing abilities; sounds may seem fuzzy or muted. This may last up to 18 hours before sounds seem normal again.

-

Your hearing may seem to return to normal, but the damage may still have occurred. Your auditory system may have permanent changes (Schaette & McAlpine, 2011).

-

Your auditory nerve pathway can be damaged, even when hearing appears to return to normal. These temporary threshold shifts may prematurely "age" the ear, similar to how sun exposure prematurely ages the skin.

-

Complex listening tasks (understanding speech in noise, nuances in music, musical sensitivity, etc.) may be permanently affected.

-

Repeated Temporary Threshold Shifts may result in permanent hearing loss (Liberman & Kujawa, 2017).

-

A good rule of thumb is this: if you need to raise your voice to carry on a conversation with someone an arm's distance away, because of the music volume, the volume could potentially damage your hearing.

-

-

Making music can result in hearing loss.

-

Performers: Almost all musicians have experienced hearing loss at some point in their careers. Many experience temporary hearing loss immediately following their performances (Chasin, 2014; Greasley et al., 2020).

-

Setting: Some venues and rehearsal spaces have dangerous volume levels resulting in an overall noise dose of 104 - 9,455% (Hodges, 2009).

-

If possible, practice in a different setting such as in a larger room or even outdoors!

-

-

Instruments: Brass, woodwind, and percussion players are particularly susceptible to MIHL. If you play one of these instruments or sit near one, you may be at an increased risk for hearing loss (Smith et al., 2019).

-

-

Other risk factors for musicians (Phillips et al., 2008).

-

Higher musical range and frequencies (high brass and woodwind players are often at a greater risk of MIHL than low brass and low strings) (Hodges, 2009)

-

Higher decibel or volume level (typically mezzo forte and higher)

-

High reverberation in the room (Smith et al., 2019)

-

Riskier placement in the ensemble (such as in front of the brass or percussion) (Smith et al., 2019)

-

Genetic makeup and lifestyle choices

-

Click here to read about genetic risks for MIHL.

-

Click here to read about the correlation between smoking and hearing loss.

-

-

High daily and weekly length of exposure (rehearsals, practice, performances)

-

Student musicians

-

In one study, over half the students experienced some amount of hearing loss during their 4 years at the university. This occurred across all instruments, including vocalists (Phillips et al., 2008).

-

-

Many years of exposure

-

Higher stress levels

-

Distaste for the musical piece (Chasin, 2014)

-

Click here for more information on hearing preservation for musicians. Click here for more information on music making and hearing loss. Click here for information on musician health and safety. There is additional information on sound awareness and safety at the UI-SAFE Facebook page here.

References

1.1 billion people at risk of hearing loss. (2015, August 12). Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/ear-care/en/

Breinbauer, H. A., Anabalón, J. L., Gutierrez, D., Cárcamo, R., Olivares, C., & Caro, J. (2012). Output capabilities of personal music players and assessment of preferred listening levels of test subjects: outlining recommendations for preventing music-induced hearing loss. The Laryngoscope, 122(11), 2549-2556.

Chasin, M. (2014). Hear the Music: hearing loss prevention for musicians. Toronto, Ontario: Musicians Clinics of Canada.

Fligor, B. J., & Cox, C. L. (2004). Output level of commercially available portable compact disc players and the potential risk to hearing. Ear and Hearing, 25, 513–527. doi:10.1097/00003446-200412000-00001

Fligor, B. J., & Meinke, D. (2009). Safe-listening myths for personal music players. The ASHA Leader, 14(7), 5-6.

Greasley, A.E., Fulford, R.J., Pickard, M., & Hamilton, N. (2020). Help Musicians UK hearing survey: Musicians’ hearing and hearing protection. Psychology of Music, 48(4), 529-546.

Hodges, D. (2009). Brains and Music, Whales and Apes, Hearing and Learning . . . and More. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 27(2), 62-75.

Hoover, A., & Krishnamurti, S. (2010). Survey of college students’ MP3 listening: Habits, safety issues, attitudes, and education. American Journal of Audiology, 19(1), 73–83. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2010/08-0036)

Hussain, T., Chou, C., Zettner, E., Torre, P., Hans, S., Gauer, J., . . . Nguyen, Q. (2018). Early Indication of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss in Young Adult Users of Personal Listening Devices. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 127(10), 703-709.

Kahari, K.R., Zachau, G., Eklof, M., et al. (2003). Assessment of hearing and hearing disorders in rock/jazz musicians. International Journal of Audiology, 42, 279-288.

Kujawa, S. G., & Liberman, M. C. (2009). Adding insult to injury: Cochlear nerve degeneration after "temporary" noise-induced hearing loss. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(45), 14077–14085. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2845-09.2009

Levey, S., Levey, T., & Fligor, B. J. (2011). Noise exposure estimates of urban MP3 player users. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54(1), 263–277. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0283)

Li, X., Rong, X., Wang, Z., & Lin, A. (2020). Association between smoking and noise-induced hearing loss: A meta-analysis of observational studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041201

Liberman, M.C., & Kujawa, S.G. (2017). Cochlear synaptopathy in acquired sensorineural hearing loss: Manifestations and mechanisms. Hearing Research, 349, 138-147.

Miao, L., Ji, J., Wan, L. et al. (2019). An overview of research trends and genetic polymorphisms for noise-induced hearing loss from 2009 to 2018. Environ Sci Pollut Res, 26, 34754–34774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06470-7

"Noise-Induced Hearing Loss." National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 14 June 2019, https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/noise-induced-hearing-loss.

Olson, A. D., Gooding, L. F., Shikoh, F., & Graf, J. (2016). Hearing health in college instrumental musicians and prevention of hearing loss. Med Probl Perform Art, 31(1), 29-36.

Phillips, S. L., Shoemaker, J., Mace, S. T., & Hodges, D. A. (2008). Environmental factors in susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss in student musicians. (Report). Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 23(1), 20-28.

Rideout, V., and Robb, M. B. (2019). The Common Sense census: Media use by tweens and teens, 2019. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media.

Schaette, R., & McAlpine, D. (2011). Tinnitus with a normal audiogram: Physiological evidence for hidden hearing loss and computational model. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(38), 13452-13457.

Smith, K., Neilsen, T., & Grimshaw, J. (2019). University student musician noise-dosage study measuring both ensemble and full-day noise exposure. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 145(6), EL494.

Verbeek, J. H., Kateman, E., Morata, T. C., Dreschler, W. A., & Mischke, C. (2014). Interventions to prevent occupational noise-induced hearing loss: A Cochrane systematic review. International Journal of Audiology, 53(0 2), S84–S96. http://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.857436

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.