See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information may be more applicable.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Hearing Aid (HA) and Music: Limitations and Problem Solving Strategies

Information for Audiologists

Hearing aids have been designed primarily to support spoken communication. Have you considered the importance of music when fitting hearing aids? Why is music of concern when it comes to hearing aids?

Music is a prevalent auditory signal, thus hearing aid users will likely be exposed to music on a regular basis. Here are some ways in which music affects people in their everyday lives:

-

Music affects our moods: People often use music to relax, to change their mood, or for entertainment.

-

Music connects us with our cultures and beliefs. Music is often a part of cultural, spiritual, community, and familial traditions.

-

Music connects us with others. Being able to enjoy events including music with one's family and friends can increase social connection and quality of life.

-

Music brings back memories. Music is often associated with special life memories - it can be like an acoustic scrapbook.

1, 2

Hearing aids are best suited for speech. They have technical limitations when it comes to music listening.

Sometimes both speech and music can occur at the same time (i.e. in a jazz club, during a movie, etc.). Even programs that detect music, speech, or background noise, can still make errors. A manually accessible speech and manually accessible music program may be beneficial to some listeners, so they can control what they hear in any given situation.

“A hearing aid optimally set for music can be optimally set for speech, even though the converse is not necessarily true.”

(Chasin & Russo, 2004)

Differences Between Speech and Music

-

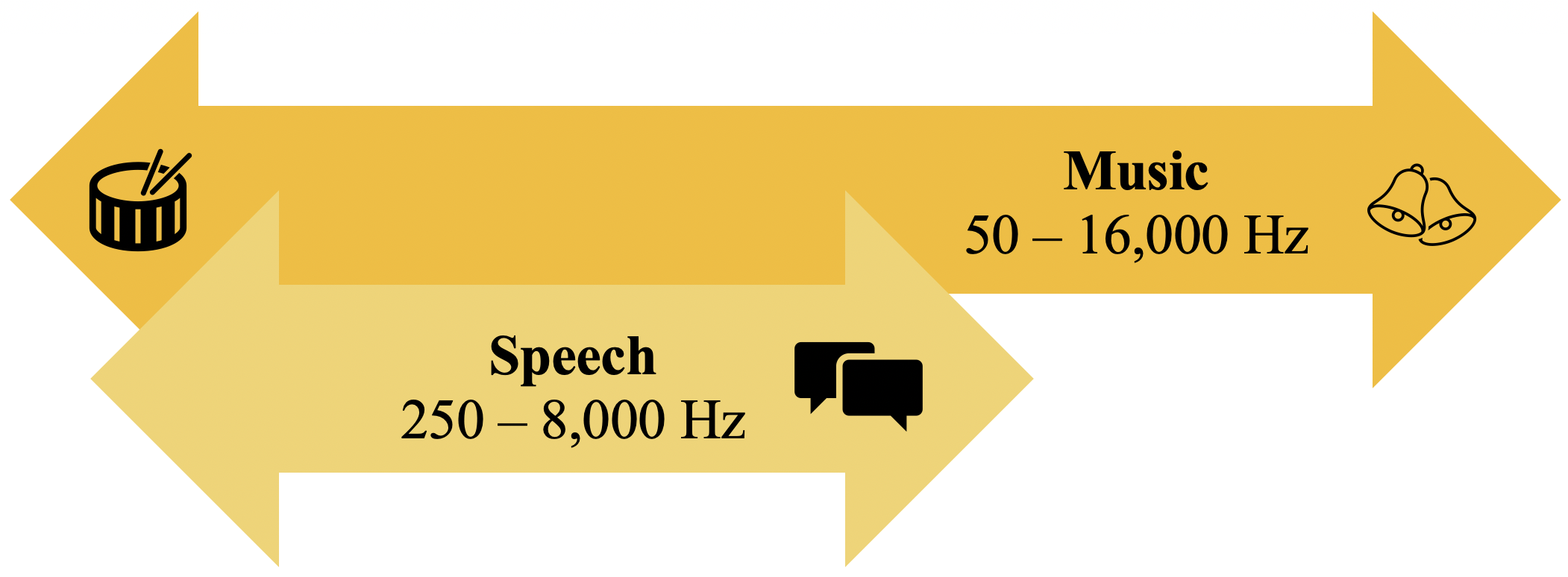

Frequency Range

-

Speech: The range of frequencies important for speech understanding is approximately 250-8,000 Hz, with most of the information for word intelligibility falling between 1,000-4,000 Hz.

-

Music: Music's frequency spectrum can range from 50 Hz (a deep bass feeling) to 16,000 Hz (the "overtones" and resonances which contribute to the distinct sound of a cymbal or bell).

-

-

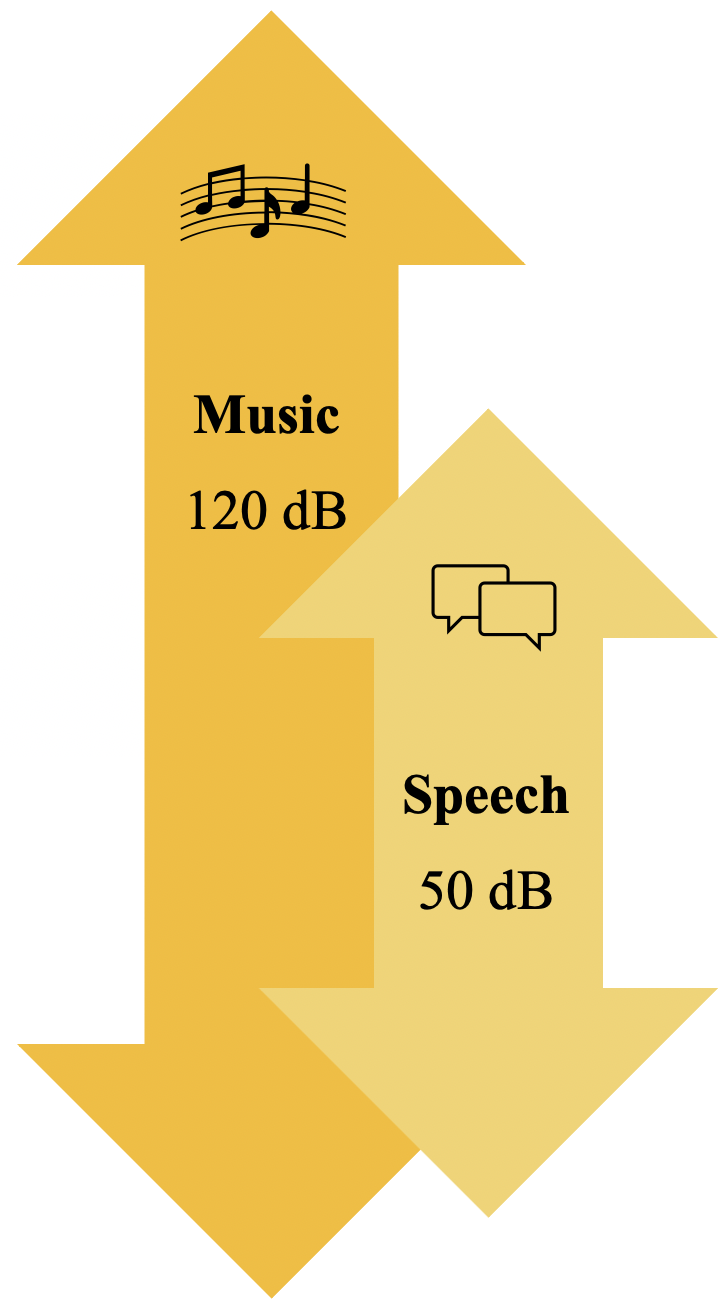

Dynamic Range

-

Speech: The dynamic range of speech is approximately 50 dB.

-

Soft phonemes of quiet speech may be as low as 32 dB while the peaks of loud speech can reach 87.

-

-

Music: The dynamic range of music is approximately 120 dB.

-

There are sudden and wide changes in dynamics. This creates expressivity in music.

-

-

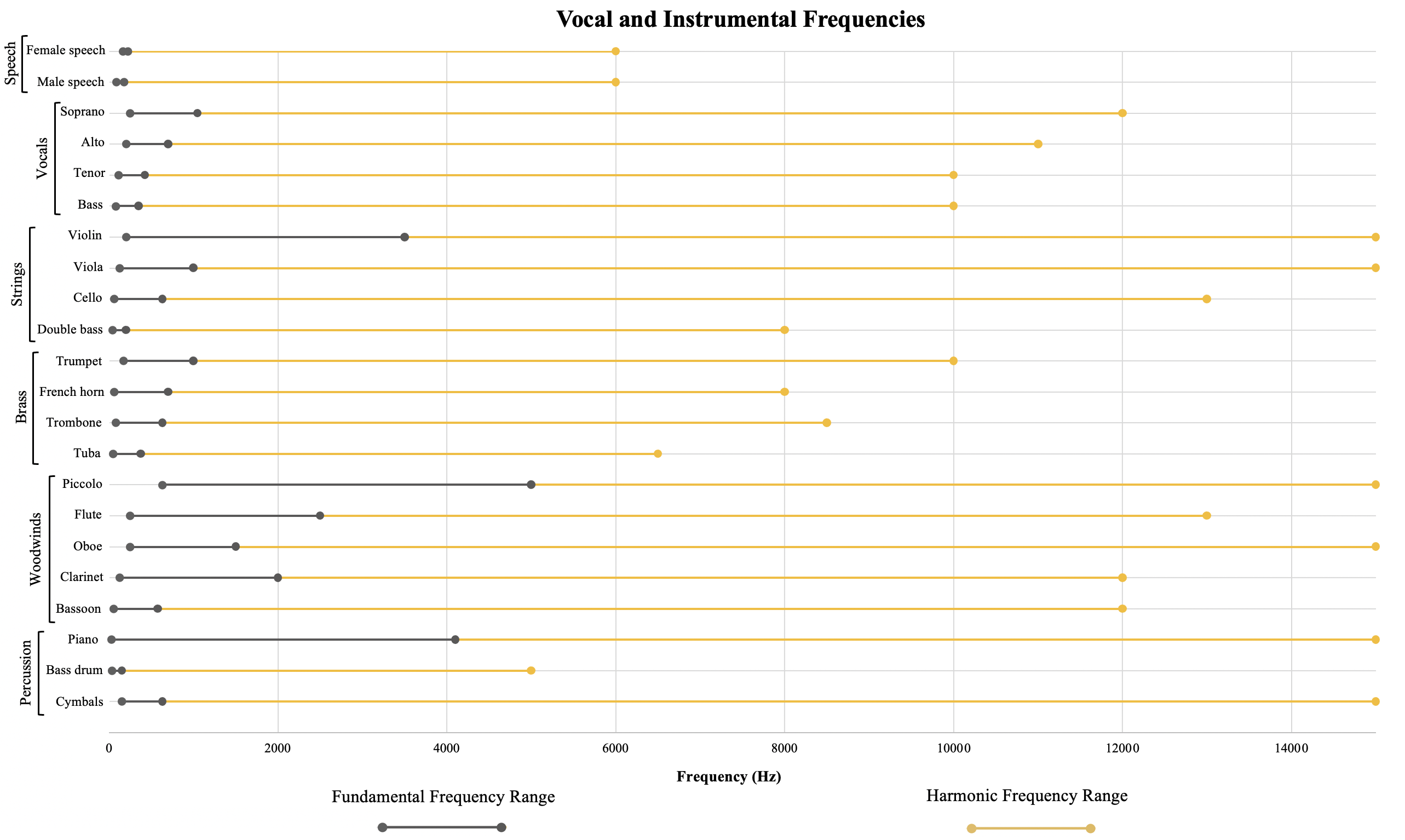

Figure 1. Graph of speech and musical instrument frequencies. Created based on data from S. Goddard et al., 2017; Loyola Marymount University - School of Film & Television.

Issues with Hearing Aids and Music

-

The main purpose of hearing aids is to maximize speech perception. Because of this, listening to music with hearing aids is not optimized and can be a negative experience for hearing aid users.

-

In a study by Wigan et al. (2017), 81% of hearing aid users reported that the quality of the music was very or extremely important to them.

-

According to Greasley et al. (2020), 67% of hearing aid users have some difficulty listening to music; yet 58% of them have never discussed that in the clinic, making this a pressing issue for audiologists.

-

Hearing aids are not designed to accommodate the wide dynamic range of music or the sudden, large changes in intensity.

-

As a result, hearing aid users may experience distortion when loud peaks or passages of music are compressed by the hearing aid.

-

Maximum power output at 95 dB SPL is adequate for speech. Music often surpasses that and may be unnaturally compressed, resulting in poor sound quality.

-

Music may lack expressivity when listening with hearing aids because compression settings do not accurately capture sudden intensity changes.

-

Automatic gain control may suddenly reduce gain for loud peaks in intensity, causing music to cut in and out.

-

Some hearing aid users report that there is a lack of clarity in the music, possibly caused by the automatic compression system.

-

Hearing aids may distort or alter the sound of music and lower the intensity more than necessary. This can make music inaudible or unpleasant.

-

50% of hearing aid users experience distortion (Madsen & Moore, 2014).

-

-

-

Hearing aids are designed to limit feedback and reduce background noise.

-

Feedback and noise management systems may erroneously treat some structural features of music as feedback or noise, causing echoes, whistles, or howls.

-

Feedback management utilizing phase cancellation may cut out higher frequencies (such as those in flutes and piccolos).

-

1 in 3 hearing aid users experiences feedback when listening to music (Fulford et al., 2016).

-

What can audiologists do to help?

-

Ask patients if music listening is important to them. If you have limited appointment time, include a few questions about music in an intake questionnaire.

-

If music is important, ask about preferences and music listening habits. Some questions to consider:

-

What kind of music do you listen to?

-

Where and how do you listen to music? Is it at a concert, outdoors, the radio, MP3 player, or in your car?

-

Do you have any issues when listening to music? Are some parts too quiet to hear, or others painfully loud?

-

-

Expectation management: This is a critical part of any hearing aid fitting, and music should be a part of this conversation as well.

-

What works for the layperson often will be unacceptable to the professional musician.

-

-

Seek more training: Take a course or attend a conference lecture on improving programming hearing aids for music listening.

-

Attending one in service on music programming can increase the confidence levels of the audiologists and the likelihood of providing music listening assistance and adjustments for their patients (Greasley et al., 2020).

-

-

Assistive Listening Devices (ALDs): Instruct patients on ALD systems and how to use them. Click the link here to read about ALD options.

-

Aural rehabilitation: Aural rehabilitation programs for individuals with hearing aids have been shown to be effective in helping improve the music listening experience.

-

Encourage enhanced listening: Music is more than an auditory experience, it can be visual, proprioceptive, kinesthetic, AND auditory. Advise your patients to enjoy music through enhanced listening methods such as:

-

reading the lyrics or sheet music

-

tapping, rocking, or dancing to the beat

-

turning up the bass to feel it in their body

-

-

Use patient-centered approaches to increase hearing aid use, sound quality, and satisfaction (Hamidi Pouyandeh & Hoseinabadi, 2019; Vestergaard et al., 2010). These include:

-

regular follow-up appointments with open-ended questions

-

structured guidance and hearing aid orientation

-

guided care and "homework"

-

hearing tactics and role play

-

written material

-

If the patient is interested in additional resources, guide them toward quality information about hearing aids and music.

-

-

-

Teach the patient: Studies have shown that hearing aid users who have greater control over their devices tend to have a more positive experience with their hearing aids (Fulford et al., 2015).

-

Teaching your patient to adjust their hearing aids for various settings - including music listening and music-making - can result in greater device use and satisfaction.

-

Hearing aid users can often make choices between subtly different hearing aid algorithmic settings for various genres of music (Wigan et al., 2017).

-

Remember that the patient is the expert in their hearing loss experience!

-

-

Show the family/caregiver/friend: Show and explain to family members how the listening experience is different through hearing aids.

-

This helps for a more understanding, patient, and supportive environment after your patient leaves the office.

-

Studies have shown that both intrinsic motivation and motivation from important family or friends can help to increase hearing aid use and success (Hamidi Pouyandeh & Hoseinabadi, 2019).

-

-

Alternative tests: Pure tone audiometry is not what music lovers listen to.

-

When performing a hearing assessment, include Speech-in-noise (SIN) tests and Loudness Scaling.

-

Encourage hearing aid users who are musicians to bring in their musical instrument for the assessment.

-

Uys and van Dijk created a music perception test for hearing aid users. Further information can be found in their research article here:

-

Uys, M., & van Dijk, C. (2011). Development of a music perception test for adult hearing-aid users. The South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 58(1), 19–47. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajcd.v58i1.38

-

-

-

-

Individualize: Include music listening experiences specific to your patient in evaluations for hearing aids and when fitting hearing aids.

Adjusting Hearing Aid Settings for Music

-

Include a program for listening to music: Croghan, Arehart, and Kates (2014) found that music listeners with hearing aids preferred slower WDRC, linear amplification, and fewer processing channels when listening to recorded classical and rock music.

-

Disable automatic functions: Disabling the automatic functions designed for speech and speech in noise is typically the first step for most audiologists.

-

Feedback cancellation: Feedback cancellation and noise reduction systems sometimes impair music listening by adding echoes, whistles, and howls.

-

Reducing or turning off the cancelation may help.

-

Some hearing aid users report that music sounds better when they turn off or minimize the feedback system.

-

-

Microphone: Adjust the microphone directionality.

-

Some patients prefer omnidirectional.

-

A fixed microphone direction might be better for live music (Greasley et al., 2020).

-

-

-

Maximum output: Adjusting the Maximum Power Output (MPO) may help increase music clarity.

-

Best adjustment will vary from patient to patient; some will prefer an increase in MPO, others a decrease (Greasley et al., 2020).

-

-

“Single channel” listening: Programming the hearing aid with a flat gain of 5-8 dB across frequencies and maximum output of 100-110 dB SPL may help provide clarity with the louder, more intense music without damaging the ear (Chasin & Hockley, 2014).

-

Frequency range: For a precipitous high-frequency loss, consider a narrow frequency range for amplification (limit high-frequency amplification) to avoid cochlea dead regions.

-

There are situations in which an extended bandwidth - i.e., frequency responses up to 8kHz or above - might be beneficial for music listening.

-

-

Linear amplification: Many listeners prefer linear amplification, especially for instrumental music and rock (van Buuren et al., 1999; Croghan et al., 2014).

-

Adjust compression parameters to obtain as linear a response as possible.

-

Gains for “Speech in quiet” programs may provide a linear response that is appropriate for music programs.

-

-

Frequency lowering: In recent years, one option for improving speech perception has been frequency shifting (for example, frequency compression).

-

This technology has the advantage of transposing the auditory signal so that the signal bypasses cochlear dead regions and stimulates parts of the cochlea that are still functioning. This can help the listener gain auditory access to high frequency consonants otherwise missing from incoming signals.

-

Unfortunately, when musical sounds are subject to frequency shifts, the change in the relationship of one harmonic to the next can result in music that sounds distorted, out of tune, or otherwise unpleasant.

-

Click the links here and here for more information about frequency shifting and music.

-

-

Clear adhesive tape: Show your patient how to place 3-4 pieces of adhesive tape (Scotch tape) on the hearing aid microphones.

-

This can decrease distortion by decreasing the input dynamic range, specifically, lowering maximum intensity peaks of music by about 10 dB.

-

-

Real ear measurements: Perform real ear measurements in the live condition while your patient listens or makes music.

-

This helps you better understand how the hearing aid is processing music and informs programming changes that can address issues.

-

-

Remember, one programming strategy is not optimal for all music or all musicians.

-

Music is diverse.

-

Hearing loss and perception is unique.

-

-

Technology is constantly changing. Stay up to date on programming options for listening to music.

What suggestions can you offer your patients to improve their experience with music?

Your patient may need some guidance on how to implement these modifications. Here are some suggestions:

Recorded Music

-

Take out hearing aids: Some hearing aid users have better music listening experiences with high-quality headphones, in lieu of their hearing aids.

-

Remind your patients that they can experiment with using their hearing aids when listening to music.

-

-

Use good sound equipment: Good noise-canceling headphones or equalizers can help improve the music listening experience.

-

By fine-tuning the gain and other sound qualities, music listeners can use their headphones, phone applications, or music players like a hearing aid!

-

-

Turn down the music volume: By turning down the volume of the music, the hearing aid can better amplify the sound.

-

Use an equalizer: By using either a physical equalizer or a digital interface equalizer on their phone or computer, hearing aid users can adjust gain in bands where their audibility is poor.

-

These can usually be installed if they are not native to the application they are using to play music.

-

Live Music

-

Attenuate input to the microphone of the hearing aid: Place 3-4 layers of scotch tape over the hearing aid microphone to reduce the sound level reaching the microphone by about 10 dB.

-

Attenuated input can help the A/D converter by decreasing the peak input levels.

-

This can help with volume, crispness, naturalness, fullness, and fidelity in music listening.

-

-

Moderation: Remind your patients to reduce exposure to loud sounds including music.

-

Sometimes people don’t realize that loud music can be as damaging to hearing as loud noises.

-

Hearing loss can be worsened with repeated exposure to loud noises, whether environmental or musical.

-

Advise patients to limit exposure to sounds above 85dB (the sound of heavy traffic or a window AC unit) to less than 8 hours per day. Click the link here for information on music-induced hearing loss and additional music listening tips.

-

References

Chasin, M. (2003). Music and hearing aids. The Hearing Journal, 56(7), 36.

Chasin, M. (2014). Hear the Music: hearing loss prevention for musicians. Toronto, Ontario: Musicians Clinics of Canada.

Chasin, M., & Hockley, N. S. (2014). Some characteristics of amplified music through hearing aids. Hearing Research, 308, 2–12.

Chasin, M., & Russo, F. A. (2004). Hearing Aids and Music. Trends in Amplification, 8(2), 35–47.

Croghan, N. B. H., Arehart, K. H., & Kates, J. M. (2014). Music Preferences With Hearing Aids: Effects of Signal Properties, Compression Settings, and Listener Characteristics. Ear and Hearing, 35(5), 15.

Fulford, R., Ginsborg, J., & Greasley, A. (2015). “Hearing Aids and Music: The Experiences of D/Deaf Musicians.” Paper presented at the Ninth Triennial Conference of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music, Manchester, UK, August 17–22.

Fulford, R., Greasley, A., & Crook, H. (2016). Music amplification using hearing aids. Acoustics Bulletin Journal, 41(1), 49-51.

Goddard, S., Beuret, L. J., Blythe, P., & Scaramella-Nowinski, V. (2017). Appendix 2: Frequency Range of Vocals and Musical Instruments. In Attention, Balance and Coordination: The A.B.C. of Learning Success (pp. 377-378). Hoboken, NJ, USA, NJ: Wiley Blackwell. doi:https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781119164746.app2

Greasley, A., Crook, H., & Fulford, F. (2020). Music listening and hearing aids: perspectives from audiologists and their patients. International Journal of Audiology, DOI: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1762126

Hamidi Pouyandeh M., & Hoseinabadi R. (2019). Factors Influencing the Hearing Aids Use and Satisfaction: A Review Study. Journal of Modern Rehabilitation 13(3), 137-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.32598/JMR.13.3.137

Holland, G. (2017). Hearing Aids and Music. Hearing Aids For Music Conference (University of Leeds).

Loyola Marymount University - School of Film & Television. (n.d.). Perceptual attributes of acoustic waves: Pitch. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from http://acousticslab.org/RECA220/PMFiles/Module05.htm

Madsen, S. M. K., Moore, B. C. J. (2014). Effects of compression and onset/offset asynchronies on the detection of one tone in the presence of another. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 135(5), 2902–2912.

Uys, M., & van Dijk, C. (2011). Development of a music perception test for adult hearing-aid users. The South African journal of communication disorders, 58(1), 19–47. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajcd.v58i1.38

van Buuren, R. A., Festen, J. M., Houtgast, T. (1999). Compression and expansion of the temporal envelope: Evaluation of speech intelligibility and sound quality. J Acoust Soc Am, 105, 2903–2913.

Vestergaard Knudsen, L., Öberg, M., Nielsen, C., Naylor, G., & Kramer, S. (2010). Factors Influencing Help Seeking, Hearing Aid Uptake, Hearing Aid Use and Satisfaction With Hearing Aids: A Review of the Literature. Trends in Amplification, 14(3), 127-154.

Wigan, M., Blamey, P., & Zakis, J. (2017). Hearing aids and music: experimental tests for better algorithm selection and design. 10.13140/RG.2.2.11457.15200.

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.