See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information may be more applicable.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Musicians with Hearing Aids (HAs):

Information for Audiologists

1, 2

Introduction

-

Hearing aids are designed to amplify speech. See Hearing Aids and Music for more information on why hearing aids are not ideal for music listening or music making.

-

Musicians’ livelihoods require sensitive, accurate auditory skills. Pitch discrimination, rhythmic timing, timbre detection, and loudness may all change with hearing loss (e.g., distortion or reduced access). Potentially, this may result in job loss and decreased quality of life.

-

Musicians have very specific auditory needs compared to average audiology patients. Hearing preservation and optimal use of hearing devices affect job security, self-identity, and quality of life.

-

Musicians play very different instruments or sing (e.g., Hz range, loudness, etc.) and make music in different settings. Consequently, their needs differ.

-

For many musicians, music making is not just a job. It is also a personal passion and self identity. Loss of quality hearing can be emotionally devastating.

-

'One-size-fits-all' approaches to musicians' services are not sufficient.

-

A standard patient in-take and service approach may be insufficient for musicians.

-

Targeted follow-up sessions focusing on music perception and enjoyment may be needed.

-

Allow time to counsel the individual regarding emotional loss and realistic expectations.

-

Meeting the needs of musicians may not be a good match for your practice; if so, consider referring musicians to other AUDs.

-

This webpage covers:

-

Common problems for musicians who use hearing aids

-

Supporting musicians as they adjust to hearing loss, hearing aids, and hearing protection.

-

Audiology appointments for patients who are musicians: patient-centered care with a musical twist

Common Problems for Musicians who Use Hearing Aids

-

Hearing aids are not well-suited for conveying complex, dynamic musical sounds

-

Digital technology is not ideal for music. Click here for more information about limitations and problem-solving strategies.

-

Due to non-linear amplification, complex sound processors, gain control, and other elements needed for amplifying speech, digital hearing aids are not ideal for music.

-

-

The real essence of the problem I have is that I need one sort of hearing aid help for playing and I need another sort for interacting and speaking during those rehearsals.

-

WDRC may cause pitch distortion

-

Feedback cancellation systems and noise reduction may cause pitch distortion

-

Phase cancellation may cut out higher frequencies

-

Musicians have reported difficulties hearing themselves play above certain notes (especially flute and piccolo).

-

-

Automatic Gain Control may cut out volume suddenly – drops and missing chunks of music

They program them so that when you get to a certain pitch or level or volume – and the whole thing just suddenly drops – and it’s like ‘Oh my God, what happened there?’ So you have to make sure that your hearing aid isn’t programmed like that – you don’t want any overly intelligent hearing aid

Supporting Musicians as They Adjust to Hearing Loss and Hearing Aids

-

Adjustment to hearing loss and hearing aids

-

Adjustment time: Explain that self-awareness of their hearing needs and capabilities will take time, just as it takes time to learn new music.

-

Determine how music listening has changed.

-

If your patient is a musician, ask about their music making or listening experiences. Are any parts of that experience lacking, difficult, or unpleasant?

-

Have them listen to or play some preferred music while in your office. Have them 'debrief' the song and tell you what went well and what did not.

-

Use real ear measures to understand how their hearing aids are processing music in relation to their feedback.

-

-

If possible, make changes to their HA settings based on feedback of sound quality.

-

Marshall Chasin's book, Musicians and Hearing Loss: A Clinical Approach (Plural Publishing, 2022) describes many specific hearing aid adjustments that can be used to improve musical sounds.

-

-

-

.Give control to the patient: Hearing aid users with greater control over their devices tend to have a more positive attitudes toward. Offer information about various assistive hearing devices or hearing aid settings they can try out.

-

-

-

Remember that musicians are the experts on their perception of music.

-

Don't hesitate to be creative; think outside the box.

-

Audiologists may not have much time to talk about music in regular appointments.

-

Consider preparing a handout of basic tips to share with your patients.

-

Share the links to the Hearig Aid User pages of this website.

-

-

-

Stigma and disclosure: Professional musicians in particular may face professional stigma if they disclose their hearing loss. A hearing aid is one visible sign of hearing loss.

-

Musicians might choose not to disclose their hearing loss, or use aids around their colleagues.

-

Musicians with hearing loss have lost jobs or job opportunities due to their hearing aids and presuppositions, so be respectful of their decision

-

Remind musicians of their anti-discrimination rights.

-

Some musicians might be confortable seeking confidential advice from another musician with hearing loss; let them know about links to advocacy groups.

-

-

-

Help musicians use their existing skills and experiences more strategically

-

Absolute or relative pitch: A study by Fulford et al. (2011) reported that many professional musicians had absolute/“perfect” or relative pitch.

-

An internal sense of pitch allows musicians to hear music in their mind’s ear by simply reading the music – like reading a book – without needing to aurally hear the pitch.

-

Encourage musicians to use their internal sense of pitch to compensate for hearing loss.

-

-

Music theory: Some musicians find that their knowledge of music theory or practicing ear-training exercises helps to fill in the hearing gaps.

-

Self-advocacy skills: Some musicians say self-efficacy is necessary at times. People may think deaf or hard of hearing people cannot play music. There are a number of hard of hearing musicians, so remind your patient that just because they have a hearing loss does not mean their music career is over.

-

Share information about self efficacy and self advocacy on these pages.

-

-

I don’t feel confident to participate in music playing in a group or alone to an audience. Unable to sing along to songs as I cannot hear the words at all. This is often noticed at social occasions. I feel isolated as unable to join in. (Greasley et al., 2020)

-

Help musicians to anticipate, prepare for special challenges playing in ensembles

-

Ensemble demands: Interactive music making, such as playing in an ensemble can create special listening challenges. Larger ensembles are usually more challenging and more complex.

-

Listening to the conductor's spoken prompts can be difficult to hear if people are playing music.

-

If the musician is willing to share their loss with the conductor, they might ask the conductor to use a remote microphone, which streams directly to the musician's hearing aids.

-

-

Hearing aids are not equally effective with spoken and musical communication.

-

-

Criticism: Harsh comments about hearing loss or unrealistic expectations from colleagues to adjust quickly to hearing loss or hearing aids can be upsetting and undermine self-confidence.

-

Anxiety: Performance anxiety may be heightened for musicians with hearing loss. They still experience typical jitters and adrenaline before a performance, but with added pressure and fear of staying in time and in tune with the ensemble.

-

Audiology appointments for patients who are musicians:

patient-centered care with a musical twist

-

Address each specific need for music making and listening: After their initial fitting, invite them to bring in their instrument to try various settings with the hearing aids. No single setting will work for all musicians.

-

Include family and friends: Take time to show and explain to family or friends of your patients how their listening experience has changed. This will help provide more understanding and social support for your patients once they leave your office.

-

Give the patient control: Help the patient establish control over their sensory experience.

-

Recommended aural rehabilitation programs, patience, and time to adjust to the hearing aids. They may need help finding local or on-line rehab programs.

-

At present, aural rehabilitation programs typically focus on speech, not music. However, strategies that increase knowledge of and self-efficacy for general hearing aid use will hopefully carry over to some music-based experiences as well.

-

-

It may be worthwhile delaying music listening with hearing aids until after the patient has adjusted to basic amplification for speech.

-

Share the links to our webpages for musicians with hearing aids by clicking here.

-

Recommend musician's earplugs to prevent further damage. Click here for more information.

-

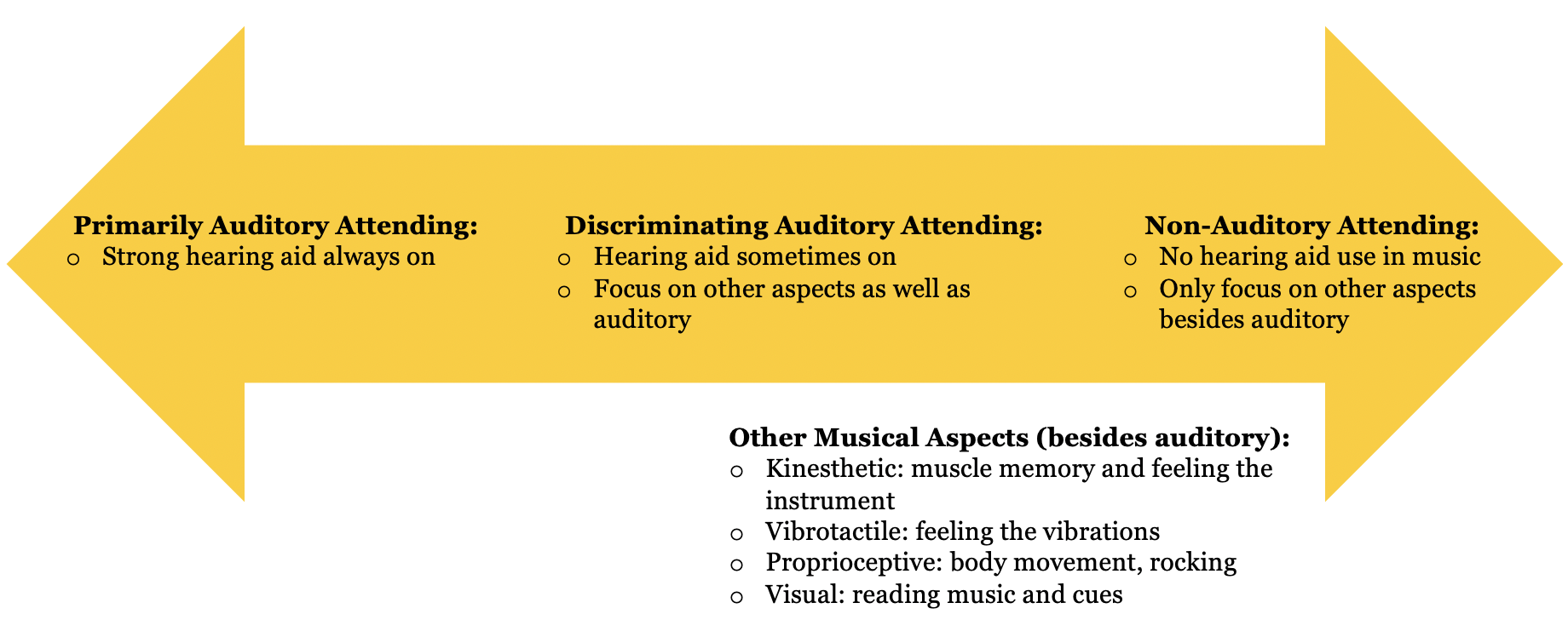

Remind them to compensate with senses involved in making and listening to music.

-

Musicians may sense vibrotactile sound wave “beats” when out of tune with his others. Feeling sound fluctuations in the body may help with tuning issues (Fulford et al., 2011).

-

-

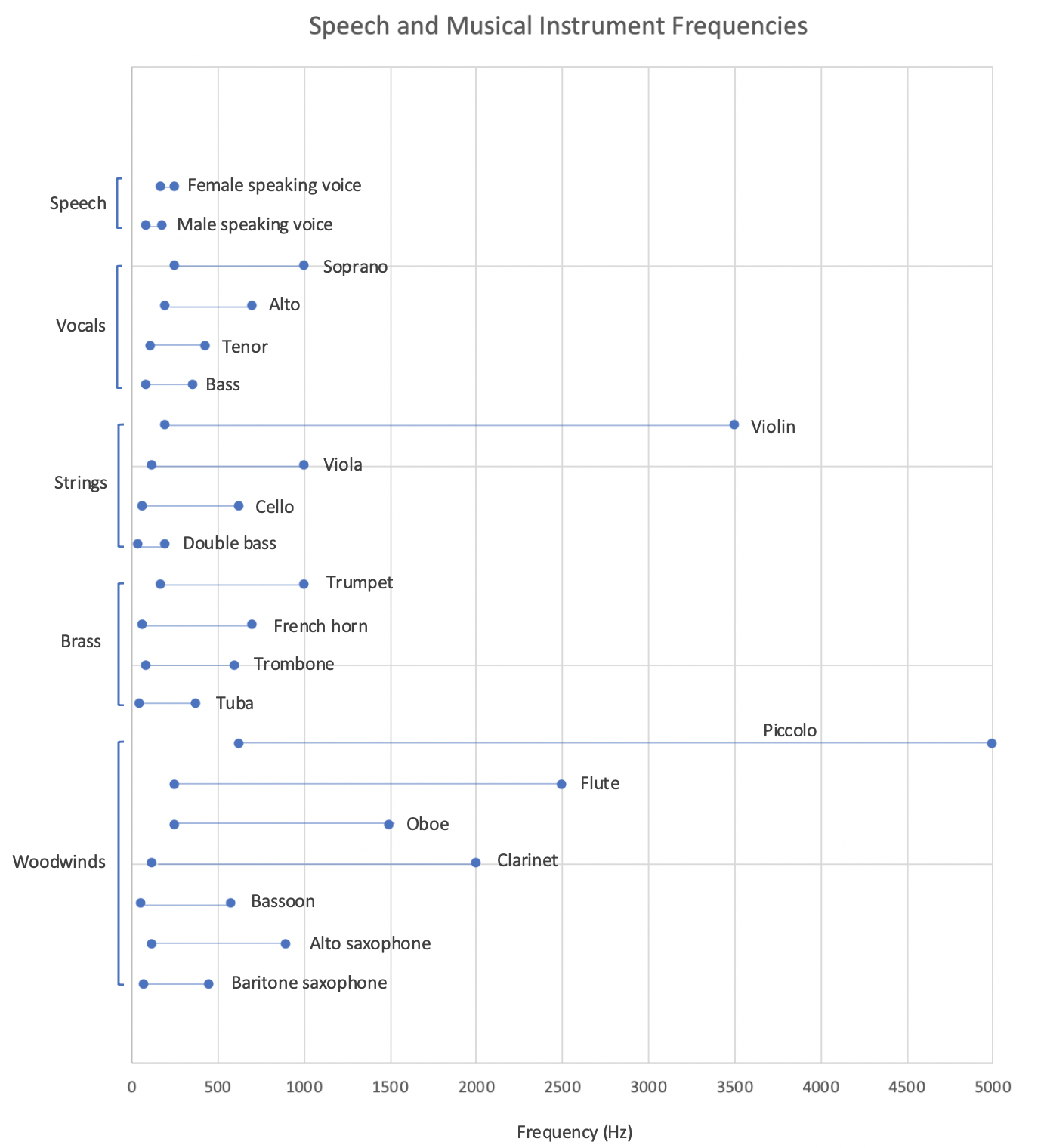

Look up your patient’s audiogram and instrument(s) they play. In the Fulford et al. (2011) study, almost all the musicians played instruments with approximate ranges within their residual hearing range. If they have a hard time hearing themselves play, suggest the idea of experimenting with a similiar instrument within their hearing range (e.g., bass saxophone rather than alto saxophone).

-

Figure 1. Graph of speech and musical instrument frequencies. Created based on data from S. Goddard et al., 2017.

-

Discuss and encourage best use of auditory attending: Many musicians have learned to use selective attention to various auditory features. These three main groups vary in auditory attending:

-

Primarily auditory attending: Some with profound deafness since birth prefer powerful analogue hearing aids

-

Discriminately attending: Some rely on their digital hearing aids some of the time, and focus on other elements as well

-

Non-auditory attending: Some use no hearing aids, but focus on kinesthetic, vibrotactile, proprioceptive, and visual elements to enhance music making and listening

-

-

Relate and encourage: Remind your patient that music will sound different after their hearing loss. But usually the way they play, their musicality and muscle memory, does not change – even if their ears play tricks on them.

-

Reciprocal learning: Musicians with hearing loss may have to teach their music teacher how best to help them. Remind them that their teacher, and you, their audiologist, are learning what the patient’s listening experience is like. It will take time to fine tune and finesse the hearing aid and rewire the brain to get the best out of music listening situations.

-

Demonstration, touch, muscle memory, and vibrotactile feedback are all favored methods of teaching for musicians with hearing loss.

-

References

Chasin, M. (2022). Musicians and Hearing Loss: A Clinical Approach. Plural Publishing.

Fulford, R., J. Ginsborg, & Greasley, A. (2015). “Hearing Aids and Music: The Experiences of D/Deaf Musicians.” Paper presented at the Ninth Triennial Conference of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music, Manchester, UK, August 17–22.

Fulford, R., Ginsborg, J., & Goldbart, J. (2011). Learning not to listen: the experiences of musicians with hearing impairments. Music Education Research, 13(4), 447-464.

Goddard, S., Beuret, L. J., Blythe, P., & Scaramella-Nowinski, V. (2017). Appendix 2: Frequency Range of Vocals and Musical Instruments. In Attention, Balance and Coordination: The A.B.C. of Learning Success (pp. 377-378). Hoboken, NJ, USA, NJ: Wiley Blackwell. doi:https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781119164746.app2

Greasley, A., Crook, H., & Fulford, F. (2020). Music listening and hearing aids: perspectives from audiologists and their patients. International Journal of Audiology, DOI: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1762126

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.