See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information may be more similar to your situation.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Hearing Aid (HA) and Music: Limitations

Information for Hearing Aid (HA) Users and Family

1, 2

[Note: For basic information about hearing loss, click here. For information about the UIHC hearing clinic, click here. For information on hearing aids, click here. For information on hearing loss prevention, click here.]

Problems with hearing aids and music

All hearing aids available today are digital, meaning they use complex signal processing to automatically amplify and compress sounds to varying degrees depending on their input levels, reduce background sounds, and eliminate feedback. They process a limited frequency and dynamic range relative to what the human ear can hear, and respond more slowly to changes in loudness than the ear. Hearing aids are programmed to optimize speech perception, which can be different from program settings to optimize music listening. Ask your audiologist about programming your hearing aids specifically for music listening.

Sometimes both speech and music can occur at the same time (in a jazz club, during a movie). Even programs that can detect music, speech, or background noise, can still make errors. Ask your audiologist for a manually accessible speech and manually accessible music program so you can control what you hear in any given situation.

Frequency Range Limitations:

-

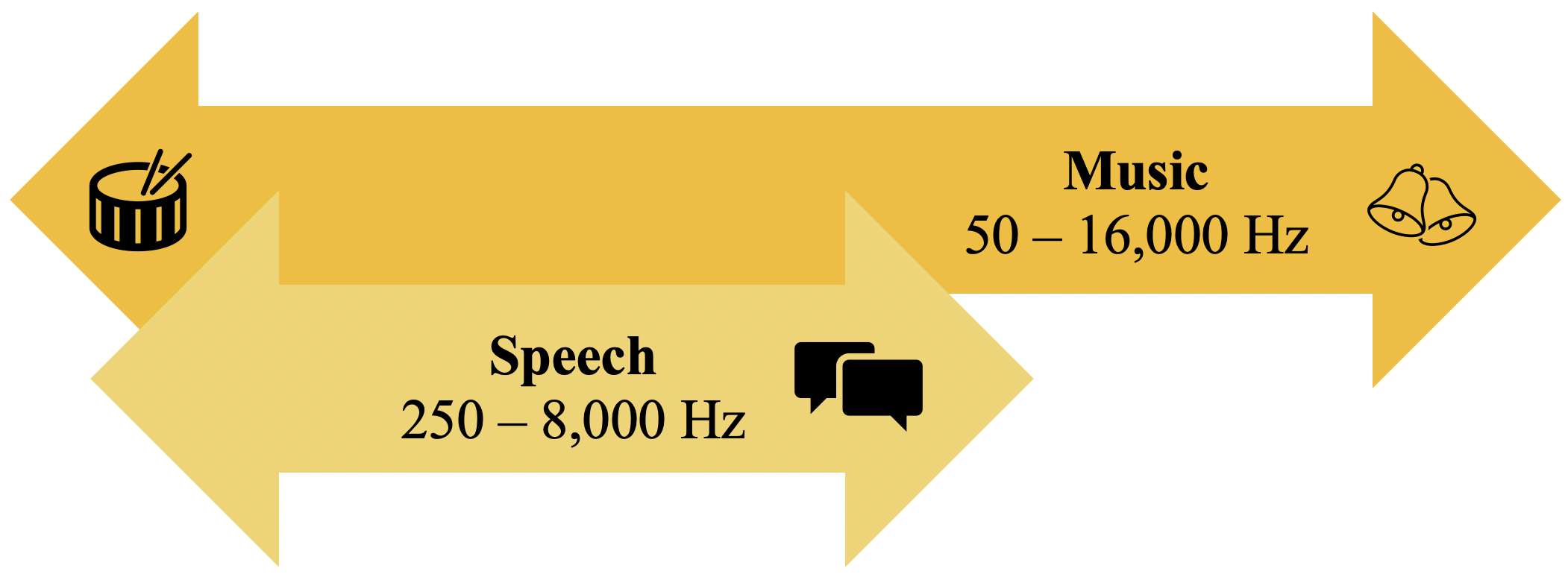

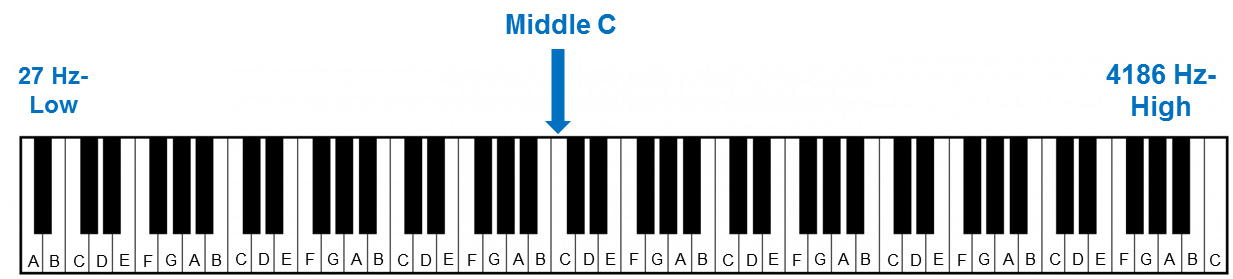

Narrow range for speech: Hearing aids are designed to amplify the frequency range of speech. Most speech sounds occur between 250-8,000 Hz.

-

Wider range for music: Music includes sounds with much lower and higher frequencies than speech. The piano and instruments in a band or orchestra make sounds primarily between 50-16,000 Hz. Hearing aids don't amplify all those frequencies.

Dynamic/Volume Range Limitations:

-

Hearing aids typically include an automatic compression system to make the loudest sounds tolerable and quietest sounds audible. They are programmed to maximize the difference in intensity between soft and loud sounds as much as possible for each individual hearing aid user; however, this range can be limited depending on the hearing aid user's degree of hearing loss.

-

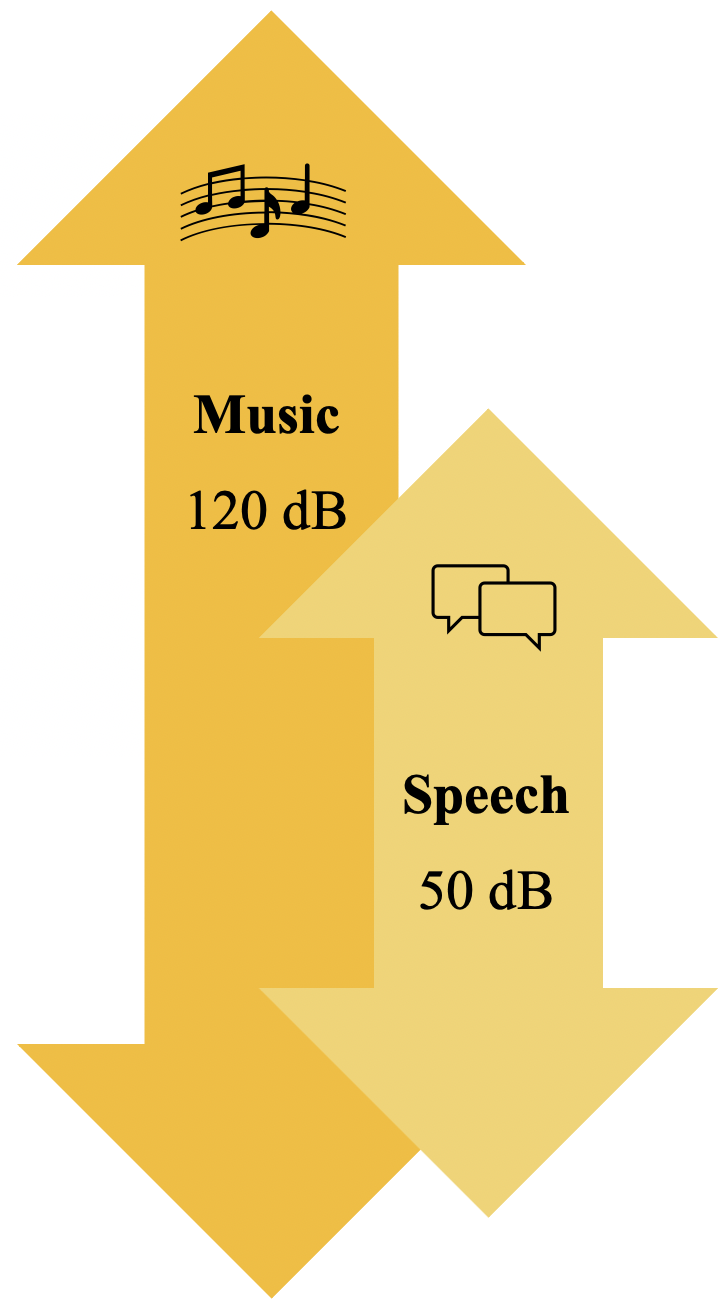

Speech sounds are fairly consistent in volume: The volume range for speech is about 50 dB. The automatic compression system of hearing aids is designed to maximize speech understanding. Speech sounds fit more easily into the dynamic range of hearing aids than music.

-

In music, loudness changes a lot: The volume range for music is about 120 dB, more than double the range for speech! Composers and musicians often use big changes in loudness (dynamics) --- soft to loud --- to make music more expressive.

-

The automatic compression system limits these changes, and thus, musical expressiveness.

-

The automatic compression system can cause the music to sound distorted.

-

-

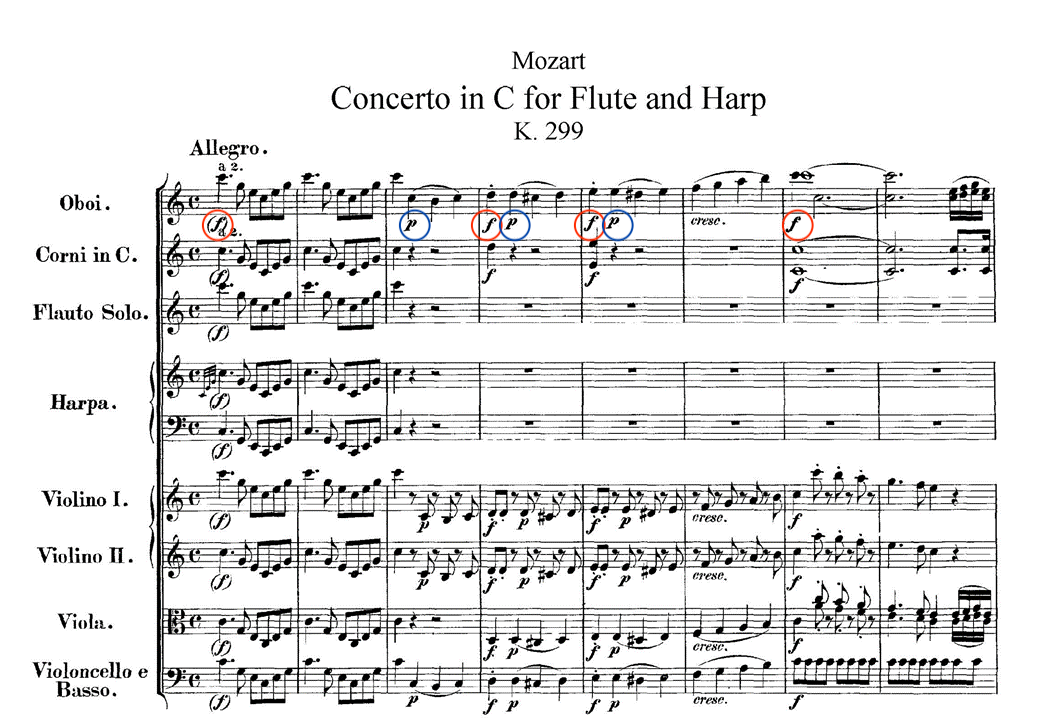

Here is an example. In this musical example, the music changes from loud (marked by a f) to soft (marked by a p) six times in less than 15 seconds!

These dynamic changes are highlighted in red and blue below to emphasize how often dynamic changes occur.

Problems Associated with Feedback Management:

-

Feedback cancellation systems: Hearing aids have a feedback cancellation system to prevent feedback, or squealing. This is very important for hearing aid users' satisfaction with their hearing aids.

-

Impact on music:

-

Feedback systems may erroneously identify musical notes and attempt to cancel them. This can result in a “phantom” tone being perceived.

-

Feedback management may be disabled for music listening to avoid affecting music perception. This can result in feedback being present when listening to music.

-

It is estimated that 1 in 3 hearing aid users experience feedback when listening to music. This can make some music sound distorted.

-

Problems in Processing Rapid Changes:

-

Automatic compression system: This is limited in how fast and to what degree it can react to changes in loudness. It is set to optimize speech understanding, which creates limitations for music listening.

-

Speech sounds: Speech sounds are more consistent in loudness and timbre (sound quality) than music. Hearing aids are more effective in conveying consistent sounds.

-

Frequent signal changes: Music tends to include many and rapid changes in loudness, frequency, and timbre (sound quality). For example, one moment, you may hear a loud trumpet blast and seconds later, there is a quiet violin solo.

-

Hearing aid technology has difficulty keeping up with these large, rapid changes in the sound signal. This can result in distortion of sound, or some parts of the sound being left out.

-

-

Frequency lowering: Some hearing aids can be set in a special way called frequency shifting (also called frequency lowering or frequency compression).

-

Certain frequencies that come into the hearing aid are shifted to slightly lower frequencies to activate more healthy, responsive portions of the inner ear. This method may help some people hear speech sounds more clearly.

-

Unfortunately, when you alter the frequencies in music, it can sound distorted or out of tune. Therefore, you should let your audiologist know if music is especially important in your life. If music IS very important, you may not be a good candidate for frequency shifting.

-

-

Hearing aids are not designed to accommodate the wide dynamic range of music or the sudden, large changes in intensity.

-

As a result, hearing aid users may experience distortion when loud peaks or passages of music are compressed by the hearing aid.

-

Music may lack expressivity when listening with hearing aids because compression settings do not accurately capture sudden intensity changes.

-

Some hearing aid users report that there is a lack of clarity in the music, possibly caused by the automatic compression system.

-

Hearing aids may distort or alter the sound of music and lower the intensity more than necessary. This can make music inaudible or unpleasant.

-

50% of hearing aid users experience distortion (Madsen & Moore, 2014).

-

References

Chasin, M. (2003). Music and hearing aids. The Hearing Journal, 56(7), 36.

Chasin, M. (2014). Hear the Music: hearing loss prevention for musicians. Toronto, Ontario: Musicians Clinics of Canada.

Chasin, M., & Hockley, N. S. (2014). Some characteristics of amplified music through hearing aids. Hearing Research, 308, 2–12.

Chasin, M., & Russo, F. A. (2004). Hearing Aids and Music. Trends in Amplification, 8(2), 35–47.

Fulford, R., Ginsborg, J., & Greasley, A. (2015). “Hearing Aids and Music: The Experiences of D/Deaf Musicians.” Paper presented at the Ninth Triennial Conference of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music, Manchester, UK, August 17–22.

Fulford, R., Greasley, A., & Crook, H. (2016). Music amplification using hearing aids. Acoustics Bulletin Journal, 41(1), 49-51.

Madsen, S. M. K., Moore, B. C. J. (2014). Effects of compression and onset/offset asynchronies on the detection of one tone in the presence of another. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 135(5), 2902–2912.

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.