See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

[Note: For basic information about hearing loss, click here. For information about the UIHC hearing clinic, click here. For information on hearing aids, click here. For information on hearing preservation, click here.]

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information below may be more similar to your situation.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Musicians who use Hearing Aids

1, 2

Ludwig van Beethoven, Bedric Smetena, Gabriel Faure,

Ralph Vaughan Williams, Evelyn Glennie

Eric Clapton, Brian Wilson, Phil Collins, Neil Young, Pete Townsend,

Huey Lewis, Sting, Ozzy Ozbourne, Stephen Stills,

Mandy Harvey, Sean Forbes, Janine Roebuck, Ayumi Hamasaki.

These musicians have lived at different times in history, and created many different styles of music. However, they all share something in common: living and making music with a hearing loss. Unfortunately, musicians are at a higher than average risk of hearing loss because they have many years of exposure to loud musical sounds. Click here to learn more about preventing or managing hearing loss.

In the days of Beethoven, people with hearing loss had to rely on very crude forms of amplification, such as ear horns. Nowadays, hearing aids are much smaller and more effective. However, they still do not cure hearing loss, and they are not as effective for music as for speech. Click here to learn more about limitations of hearing aids and music as well as tips for listening.

This webpage describes:

-

some challenges faced by musicians who use hearing aids

-

strategies that can support more satisfactory music making experiences, despite the limitation of hearing aids.

Challenges Experienced by Musicians with Hearing Aids

-

Hearing aids are designed to amplify speech. Listening to music through a hearing aid is not ideal.

-

Hearing aids have difficulty processing the complex and rapidly changing combinations of pitches, timbres and loudness in music.

-

Hearing aids cover a more narrow range of pitches than those played by musical instruments.

-

Some musical features may get distorted, sound artificial, or get left out entirely.

-

Click here to learn more about hearing aid limitations for listening to music.

-

-

-

The limitations of hearing aids for music can be emotionally frustrating for musicians.

-

Musicians may grieve the loss of musical beauty as they used to know it.

-

It can take time and practice to adjust to how music sounds with a hearing aid.

-

Some situations will be better than others, depending on the music, the environment, and how you are feeling at the time.

-

It can be challenging to set realistic expectations.

-

What is a good balance between effort toward optimal listening and acceptance of the sound? This may change from one moment to the next.

-

-

-

Hearing aids do not distinguish between desired sounds and noise like your brain can. This can affect the on-going feedback from your own instruments and fellow musicians.

-

Musicians with hearing aids may have difficulty hearing instructions from a conductor or fellow musicians while the ensemble is still playing.

-

-

Hearing aids are less effective in poor acoustic environments. Music making in a reverberant rehearsal space or concert hall can make the notes all blur together.

-

The technical limitations of the hearing aid, paired with damage to the ear, can make tuning your instrument with others more challenging.

-

The extra effort required to hear music accurately can result in fatigue and second-guessing one's musicianship; this can increase performance anxiety.

-

Musicians may worry about discrimination or shaming by other musicians if they admit to a hearing loss.

Strategies for Optimizing Music Making Experiences

-

No single approach will work for everyone:

-

Be creative. Experiment to see what works best for you in working with and around your hearing loss.

-

-

Learn from other musicians with hearing loss:

-

Explore online advocacy groups for musicians with hearing loss, such as: https://www.musicianswithhearingloss.org/wp/

-

-

Focus on different forms of satisfaction when making music:

-

Music is multisensory: Music provides much more than an auditory experience. Pay attention to all your senses.

-

Social benefits: Focus on the joy of sharing music making as well as the auditory output.

-

Emotional memories: Making and listening to music is an emotional experience. Reminisce about songs your parent may have sung to you as a child. Remember songs from your teenage years that you shared with your friends. Music is tied with memories and emotions. Your memories of music can help you make sense of a less than perfect sound.

-

-

Use your skills and experiences to compensate for imperfect hearing:

-

Use your internal recollection of pitch: Some people with hearing loss may still be able to hear music in their mind’s ear by simply reading the music – like reading a book – without needing their physical ear to hear the pitch.

-

Music theory: Musicians with hearing loss may benefit from drawing on their knowledge of music theory to help fill in the auditory gaps.

-

Self-advocacy:

-

You may need to stand up for yourself. If someone says deaf or hard of hearing people cannot make music, prove them wrong!

-

Request better seating and visual access in rehearsals or concerts.

-

-

-

Remember, practice makes perfect:

-

Just as it takes time and repetition to perfect musical skills, it will take time and practice to adjust to your new hearing aids.

-

-

Keep track of what works, and what doesn't:

-

Take notes in a journal or diary of which adjustments are easy, and what aspects of hearing you miss. Do this when listening or making music.

-

Take your notes to follow-up appointments and tell your audiologist what is missing in music.

-

While hearing aids are not perfect, your audiologist may be able to adjust some features so your music listening and music making experiences are improved.

-

Some specific things to listen for and take note of include:

-

Volume – are some parts of music too quiet, so loud they hurt, or does the entire sound cut out at times?

-

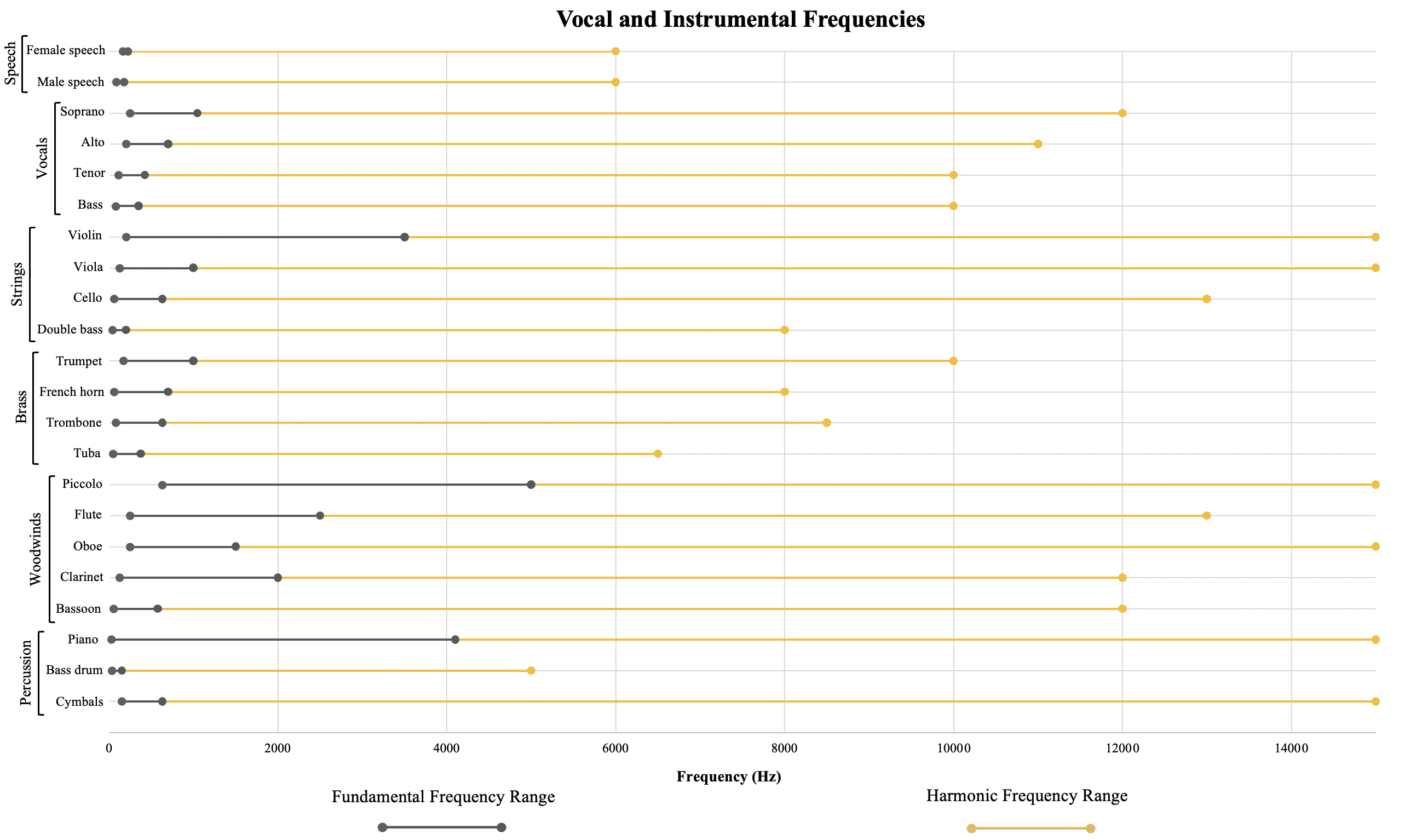

Range – can you hear the full continuum of pitches, or do certain instruments cut off (high trumpets, flutes, piccolos, or low bass drums)?

-

Timbre – does the music sound clear or do the instruments sound unnaturally rough or scratchy?

-

Pitch – have others told you that you’re out of tune, even though to your ear you sound in tune? Do other instruments sound out of tune constantly?

-

-

-

-

Disclosure: It is up to you if or when you want to disclose your hearing loss.

-

There are anti-discrimination laws to protect you from losing your job due to your hearing loss.

-

There are accommodations in many settings to help improve your hearing experience.

-

-

YOU are the expert of your hearing loss: The audiologist sees the graph and knows the medical terminology for what you are experiencing, but YOU are the one who can actually hear what is going on.

-

Choose an audiologist who is the right match for your needs as a musician.

-

Audiologists have different life experiences and expertise related to music.

-

Ask about the audiologist's experiences working with musicians.

-

Does the audiologist have some musical background?

-

Ask if the clinic offers follow-up appointments to focus on special issues related to music perception.

-

This might take the form of individualized counseling to explore strategies for optimizing complex listening situations, such as listening to music, attending concerts, or playing music.

-

-

-

-

You can find more information on self-efficacy and self-advocacy at these web links: here and here

-

-

Tips to manage the sensory experience

-

To wear or not to wear: About half of hearing aid users report that their aids improve music enjoyment.

-

Some people prefer not to use hearing aids when listening to or playing music.

-

Others have a favorite setting on their hearing aid.

-

Try playing music with hearing aids out, and listen with them in – or vice versa. Find out what works for you.

-

-

Aural rehabilitation: Ask your audiologist about aural rehabilitation programs for hearing aid users.

-

Current aural rehabilitation programs usually focus on listening and attending to various aspects of speech; however, some of the strategies may also help with some aspects of music.

-

-

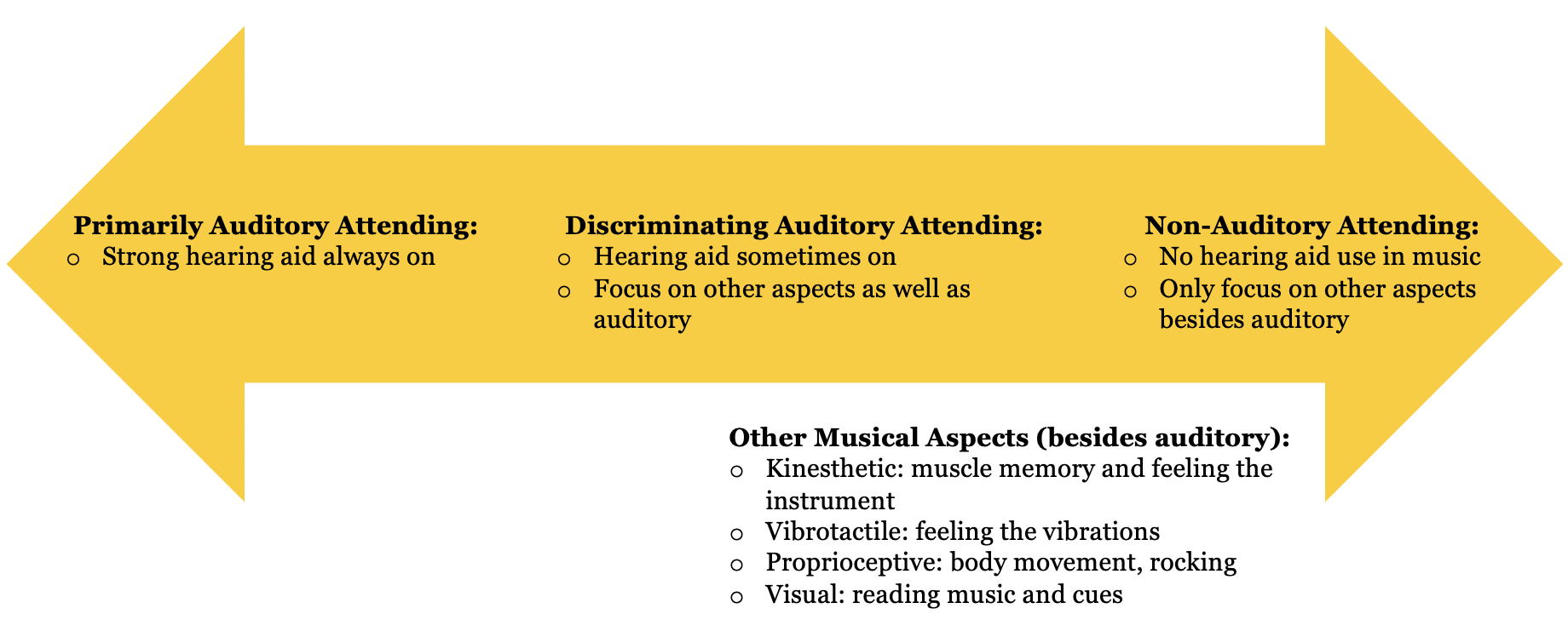

Musical aspects: There is a wide spectrum of auditory attending or “listening." Listening involves more than the ears, so try focusing on other aspects of the music making experience to see what makes it most enjoyable for you.

-

New instrument: You may have a better experience playing an instrument within your residual hearing range. For those who have lost higher frequencies, flute and piccolo may be difficult to hear, and those who have lost lower frequencies, bass, trombone, or tuba may be challenging. Consider learing a new instrument (e.g., viola instead of violin)!

-

Figure 1. Graph of speech and musical instrument frequencies. Created based on data from S. Goddard et al., 2017.

-

New experience: Music will sound different after your hearing loss. But your musicality (how you play), does not change – even if your ears play tricks on you.

-

Technology: Talk to your audiologist about programming your hearing aids with a wider frequency range or linear amplification.

Music Making Challenges and Strategies

-

Interactive music is challenging

-

Ensemble: Interactive music making, such as playing in an ensemble can create many new listening challenges.

-

Smaller is easier: As you try and adjust to your hearing loss, it may be best to begin with a smaller ensemble such as a duet, trio, or quartet. Larger ensembles are usually more challenging and have more complex listening environments.

-

Anxiety: Performance anxiety may be heightened for musicians with hearing loss. You still experience the typical jitters and adrenaline before a performance, but also may have an additional focus and fear of staying in time and in tune with rest of the ensemble. Consider meditative or breathing techniques to help you stay calm.

-

-

Personal strategies

-

Less talking while playing: Talk to your section members and the conductor. Explain that it is difficult to hear their cues over the sound of the orcestra. Some conductors will shout counts or cues while still conducting. These directions are often difficult for hearing and hard of hearing musicians to understand!

-

Ask for the music in advance: With a hearing loss it may be beneficial to learn and memorize parts ahead of time so you can watch the conductor more. If you’re able to access the score, take some time to read and listen to it so you recognize important entrances, melodic lines, and the overall feel of the piece.

-

Friendly feedback: Feedback from others in the ensemble can be helpful for continued growth. Having a trusted colleague or peer in the same section inform you when you are out of tune, or rushing, or sounding great can help boost your confidence in your musicianship and help you, and the ensemble, sound the best.

-

Listening with a hearing loss can be tiring; build in time for mental and physical rest

-

-

Make optimal use of visual cues; let your eyes help your ears!

-

Clear downbeat: Raising a wind instrument may help provide the visual cue of the downbeat for people with hearing loss, both in the ensemble and in the audience.

-

Upcoming entrance: Raising an instrument up to the mouth may also provide a visual cue of an upcoming entrance.

-

Reinforced beat: Foot tapping to the beat may also act as a visual representation of the beat.

-

Unobstructed sight lines: Where you are seated in the rehearsal is important. Make sure sight lines are clear to the conductor and other key members of the ensemble to help with visual cues.

-

Tell the conductor what sorts of cues you need!

-

-

Pay attention to physical cues

-

Embouchure: Tune by paying greater attention to embouchure. This is particularly visible in the flutes and other woodwind instruments, and is helpful when the entire ensemble is going slightly sharp or flat and you must adjust with them.

-

Metronomes: Mechanical metronomes worn on the wrist and felt allow you to stay in time when rehearsing, and free up your eyes from a light metronome.

-

-

Try new approaches to learning and communication.

-

Reciprocal learning: You may have to teach your teacher how to best help you. This is an example of self-advocacy.

-

Non-auditory methods: Musicians with hearing loss report that demonstration, touch, muscle memory, and vibrotactile feedback are all helpful instructional methods.

-

Sound descriptions: Teachers should use analogies and visual imagery to demonstrate complex moods and timbral colors in the piece. They also may need to substitute some of the “sound words” related to volume, modality, texture, and melody. Forte which typically means “loudly” for musicians, may need to be described as “with more air” for musicians with hearing loss.

-

Creativity, imagination, and open-mindedness are necessary for growth in both the teacher and student with hearing loss.

-

References

Fulford, R., Ginsborg, J., & Goldbart, J. (2011). Learning not to listen: the experiences of musicians with hearing impairments. Music Education Research, 13(4), 447-464.

Fulford, R., J. Ginsborg, & Greasley, A. (2015). “Hearing Aids and Music: The Experiences of D/Deaf Musicians.” Paper presented at the Ninth Triennial Conference of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music, Manchester, UK, August 17–22.

Goddard, S., Beuret, L. J., Blythe, P., & Scaramella-Nowinski, V. (2017). Appendix 2: Frequency Range of Vocals and Musical Instruments. In Attention, Balance and Coordination: The A.B.C. of Learning Success (pp. 377-378). Hoboken, NJ, USA, NJ: Wiley Blackwell. doi:https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781119164746.app2

Greasley, A., Crook, H., & Fulford, F. (2020). Music listening and hearing aids: perspectives from audiologists and their patients. International Journal of Audiology. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1762126

Leek, M.R., Molis, M.R., Kubli, L.R., & Tufts, J.B. (2008). “Enjoyment of Music by Elderly Hearing-Impaired Listeners.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 19(6), 519–526. doi:10.3766/jaaa.19.6.7.

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.