See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information may be more applicable.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Diversity Among People with Hearing Loss:

People with Hearing Loss Differ in Many Ways

1, 2

Introduction

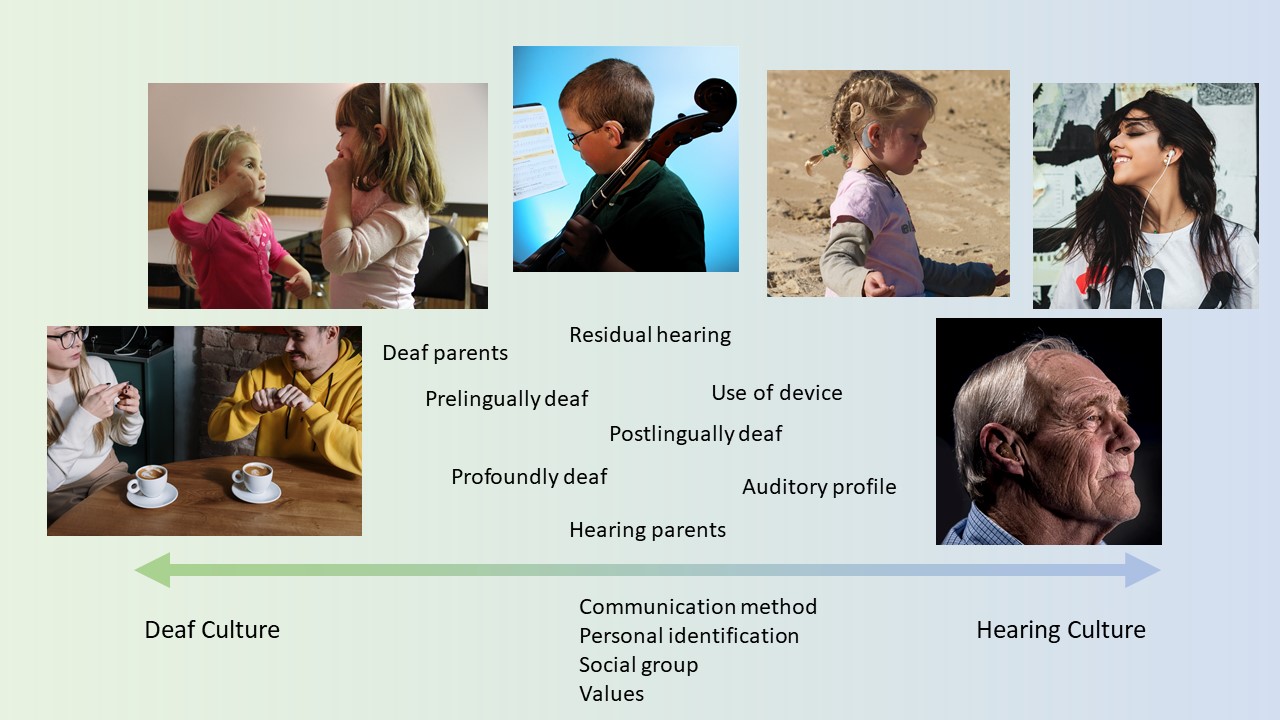

As the picture above shows, people with hearing loss make up a diverse group. While they share in common a hearing loss, they can differ from one another in many ways. It is common to talk about differences in the hearing loss itself, such as when the loss started, the type of loss, and how severe it is. In addition, people with hearing loss are diverse (differ within the group) in how they live their lives:

-

How they communicate:

-

Do they prefer to communicate through sign language or through speech?

-

-

The attitudes of their family about hearing loss:

-

Does the family consider hearing loss a disability or a cultural difference?

-

-

Who they choose to socialize with:

-

Do they like to interact mostly with hearing people (communicate with listening and speaking), or do they prefer socializing with other people who have hearing loss?

-

-

Their personal identity in relation to their hearing loss:

-

Do they consider their hearing loss a central part of who they are—their identity?

-

-

Their choices about using hearing devices (hearing aids, cochlear implants):

-

Do they rely heavily on hearing devices, or do they prefer not to use them?

-

-

Their attitudes about music:

-

Do they enjoy music, or is music not an important part of their lives?

-

These differences can affect whether a person feels more a part of a hearing or Deaf culture or something in between.

This page provides an introduction to Deaf culture, and how it differs from hearing culture—that is, relying on spoken communication. (Note: This page reflects primarily Deaf culture within the United States. Attitudes and behaviors regarding hearing loss vary from one country to the next.)

This page also provides a brief introduction to the complex topic of diversity (differences) among people with hearing loss, personal identity, and something called cultural affiliation. There are many other websites that discuss Deaf culture, but this one has a special focus on music. For further information on how Deaf identity is expressed, please see our companion page about the Deaf identity expression.

Topics covered on this page include:

To illustrate diversity among people with hearing loss, we provide vignettes of people who differ in age, their auditory profiles, family circumstances, personal interests, and attitudes toward music.

What is Deaf Culture?

Culture is hard to define. In 1871, E.B. Tyler defined culture as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, law, morals, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” This definition is still used today and can help us to understand Deaf culture. People who are culturally Deaf are part of a community who shares values and life experiences.

-

When the word Deaf appears with a capital "D", that indicates a cultural connection that includes shared language (sign language) and customs.

-

In the United States, the people in Deaf culture shared a language: American Sign Language (ASL).*

-

A person’s use of ASL often indicates how much they identify as Deaf in the United States (more on that below.).

-

Some people who have normal hearing, but who socialize with friends and family in Deaf culture may feel more a part of Deaf culture than hearing culture.

-

-

The word deaf with lower case "d", usually refers to the audiological condition of having little usable hearing.

-

People who are deaf, but not Deaf, may socialize more often with people who are hearing.

-

People who affiliate with Deaf culture often go to school for the Deaf, attend Deaf events (such as plays that use sign language), and enjoy Deaf art. Deaf identity and culture also intersect with other types of identity and culture such as race, ethnicity, nationality, sexuality, and gender. Therefore, some people may identify primarily as a part of one culture and secondarily as Deaf or vice versa.

This page focuses primarily on music in the lives of people who have hearing loss, including those who are part of Deaf culture. The Music and Hearing Loss Team that prepared these web pages is primarily made up of hearing people. We acknowledge that it is not our place to represent or speak on behalf of Deaf people. Please see our statement on Deaf culture and resources by and for the Deaf community.

Personal Identify and Cultural Affiliation

Factors that affect personal identity and cultural affiliation: Deaf or hearing

There are many things that play a role in whether a person feels like they are part of Deaf culture or hearing culture including:

-

Family, education, and friends

-

Onset of hearing loss

-

Auditory profile

-

Use of a hearing device like a cochlear implant or hearing aid

Family, Education, and Friends

As with any culture, the family you are born into has a large impact on identity and culture. Genes that affect hearing can be passed down to children, therefore, a hearing loss can run in families.

Culturally Deaf Families

-

If someone was born into a culturally Deaf family in the United States, their first language is likely American Sign Language (ASL).

-

Everyone in the family will use sign language, no matter their hearing status.

-

Even family members with normal hearing may identify with Deaf culture.

-

-

Feeling part of Deaf culture may be even stronger if a child attends a Deaf school or has good friends who encourage sign language and other Deaf values.

Families That Are Part of Hearing Culture

-

People who lose their hearing well into adulthood are more likely to feel a part of hearing culture.

-

A person who loses hearing well into adulthood is likely to have hearing friends and will have developed attitudes and habits based upon hearing (such as listening to music, using spoken language to communicate).

-

The older a person is, the more time and effort it takes to learn any new language, including sign language.

-

-

If the family and their friends communicate primarily with speech, the child will grow up initially within a hearing culture.

-

If someone born with a hearing loss grows up with hearing parents, the parents may focus on using spoken communication.

-

Some hearing parents may learn sign language to communicate with their child.

-

Parents may use sign language along with speech to encourage spoken as well as signed communication.

-

-

Later in life, a child from a hearing family may have exposure to Deaf culture if they go to a school for the Deaf or if they have good friends who use ASL. That child may feel like they are part of both hearing and Deaf culture.

Our early childhood experiences with music are shaped by our parents and caretakers. Interest in music varies from one family to the next, regardless of hearing status. Children whose parents do not listen to music may not respond to music as positively as those who do.

Emma has normal hearing but was born to two Deaf parents. Her first language was American Sign Language, which is all she used for the first few years of her life. She is an expert signer and has many friends at the local Deaf club she and her family attends. Her parents decided to enroll her in a hearing kindergarten to help her participate in both hearing and Deaf cultures. Emma prefers to sign and is a little behind in her spoken language for her age, but young children can often learn to communicate easily in two different languages. She associates music with cartoons because that’s primarily where she hears it—not as something that people listen to for enjoyment. In fact, one day at the supermarket, she asked her father where the cartoons were coming from, and it took quite a while to clear up the misunderstanding.

Onset of Hearing Loss

The time at which a person loses their hearing, or the onset of their hearing loss, impacts their spoken language learning. The earlier and the more severe the onset, the greater the impact on spoken language.

-

Prelingual loss: hearing loss before the age at which typically developing children learn to speak.

-

Children with prelingual deafness will not learn how to use spoken language fluently unless they receive early interventions, such as hearing devices or speech training

-

-

Perilingual loss: hearing loss during the development of spoken language (from around 2 to 4 years of age.)

-

Children with perilingual losses may have slight differences in speech clarity and rate of language development.

-

-

Postlingual loss: hearing after spoken language has been established.

-

Children with postlingual losses may be oriented toward the spoken language, especially if their family and friends use spoken language.

-

People who start learning sign language at an older age may not develop as fluent sign language as children who grew up in a signing household.

-

Onset of hearing loss and choice of spoken or signed communication is not cut-and-dried. Furthermore, the severity of the hearing loss is not the only reason for choosing sign language over spoken communication.

Onset of language and music participation

-

Children with prelingual hearing loss may have more difficulty understanding the lyrics of songs than children with postlingual hearing loss.

-

They may have missed out on vocabulary during a critical developmental period at which they were learning spoken language.

-

They may have difficulty hearing the words in a song because the words can be covered up by an accompaniment.

-

-

Perceiving and enjoying some parts of music, such as rhythm, may be easier, especially if:

-

They can get tactile or visual cues.

-

The pulse of the notes can be heard through their residual hearing or hearing device (see below.)

-

Sylvie was born profoundly deaf. She received a cochlear implant (CI) as a baby, so she has only heard music through a CI. CIs transmit speech very well, but not musical pitches or tone quality. (See our pages on CIs for more information) Sylvie uses spoken communication. Her speech and language are developing at a slighter slower rate than her typically hearing classmates. Therefore, she sees a speech and language pathologist (SLP) to improve those skills. She likes to sign with some other deaf kids at school, but she is more accustomed to speaking because that is how her family communicates. Sylvie attends music classes and is a little bored with the singing portions, but she loves to explore rhythm instruments! Her hearing parents have talked about enrolling her in a band when she gets into fourth grade. They want music to be a fun part of her life and aren’t trying to pressure her with any sort of formal music training just yet.

Hearing Profile

The term, hearing profile includes how easily a person can hear sounds of different pitches (low to high). A typical human ear can perceive sounds from around 20 Hz (low) (which is one of the lowest notes on the piano) to about 20,000 Hz (high) at birth. People with hearing loss differ from one another in what pitches they can hear most easily. One way to "show" which sounds a person can or cannot hear is called an audiogram.

![]()

This chart shows a range of low to high and soft to loud sounds, different levels of hearing loss, and which sounds you can or cannot hear, depending upon your hearing loss. For example, a person with a profound hearing loss may not even be able to hear the sound of an airplane, while a person with a moderate hearing loss may or may not be able to hear a baby crying.

-

On the left side of the chart is the volume of a sound in decibels (dB, a term used to describe sound energy). Louder sounds are toward the bottom, and softer sounds are toward the top.

-

Across the top of the chart is the frequency of a sound in hertz (Hz); how low to high a sound is.

-

Lower sounds are toward the left, and higher sounds are toward the right.

-

How high or low a frequency sounds to the listener is called pitch. For example, middle C on the piano is just about 250 Hz.

-

Melodies are made up of a sequence of pitches that go higher, lower, or stay the same.

-

Harmonies are made up of several different pitches that are heard at the same time.

-

-

The vowels and consonants that make up human speech are shown within the banana shape toward the top of the audiogram (called the speech banana).

-

The speech banana shows how high/low and how loud/soft speech sounds are. For example, the letter, "s" is made up of a higher and quieter sound than "e" or "u."

-

Many musical instruments also fall within the frequency range of human speech. However, musical instruments can sometimes be played louder than human speech. This can make some music easier to hear than speech.

-

-

-

On the right side of the graph are levels of hearing loss, from normal at the top or the chart, to profound loss at the bottom.

-

People with normal hearing can hear very quiet sounds. They can hear the rustling of leaves or the singing of birds.

-

People with moderate to severe cannot hear quiet sounds but may be able to hear some louder sounds, such as dogs barking, vacuum cleaners, or phones ringing.

-

People with mild to moderate hearing loss in the middle frequency range will have difficulty hearing some speech sounds depending upon their particular hearing profile.

-

Many people can compensate for hearing speech sounds by using context, lipreading, or hearing devices if their hearing loss is not too great.

-

People with more severe hearing loss may learn sign language or receive a cochlear implant to communicate.

-

-

Auditory profiles can come in different shapes and levels of severity.

-

Some audiograms slope downward (called a sloping loss). That means the person has a better hearing for lower sounds and poorer hearing for higher sounds.

-

Some audiograms are called a flat loss. The loss is similar from low to high sounds.

-

Some hearing losses are notched. That means the hearing loss is more severe in a narrow frequency range (for example, from 2000 to 3000 Hz).

How does hearing profile affect music listening and enjoyment?

-

People with sloping hearing losses are more likely to hear lower instruments, such as kick drums and bass better than higher instruments such as cymbals, shakers, flutes, or violins.

-

Perception of harmony and timbre will likely be affected as well as melody, depending upon which frequencies are hardest to hear.

-

People who have more severe hearing loss in higher frequency may prefer music that has lower instruments or more emphasis on rhythm.

-

Stacy has a moderate, sloping hearing loss in both ears due to an illness she had when she was five years old. She has some difficulty hearing higher consonants and will sometimes mix up words like “thin” and “fin.” She has become an adept lip-reader and has a rich social life with hearing friends and family. Stacy loves electronic dance music, frequently attends music festivals, and listens to music on her phone. She loves that she can use the accessibility settings on her phone to boost the high frequencies of the music. That helps her accommodate for her hearing loss. She is considering getting hearing aids but wants to live without them for the time being.

Use of a Hearing Device

Some people with hearing loss use hearing devices (hearing aids and cochlear implants) to help them hear spoken communication. Other people do not. Some people may use hearing devices only in certain circumstances. People may choose not to use hearing devices at all because:

-

they are part of Deaf culture, and they communicate mostly through sign language.

-

hearing devices are not very helpful for their particular auditory profile.

-

hearing devices can be uncomfortable.

-

hearing devices are not very effective for conveying some types of musical sounds.

For more information on hearing devices, check out our pages for hearing aid users and cochlear implant users.

Some people find that hearing devices can improve some aspects of their music listening experiences, especially if the person is comfortable with technology and experimenting with different settings. Many hearing devices can input music directly from music players like a phone or mp3 player. Many concert venues have a "hearing induction loop" that can transmit music to hearing aids fitted with a t-coil. For information on improving the sound of music through a hearing aid, please see our pages on using hearing aids to listen to music at home and at concert venues.

Allen has spent his whole life in hearing culture. He took his hearing for granted until he started to lose his hearing as he got older. He got hearing aids so that he can converse with his wife more easily, watch his TV shows, and listen to orchestral music. Allen is finding his new hearing aids a little bit overstimulating or harsh from time to time. His hearing aids seem to work better for some musical selections than others. Sometimes, he finds that music sounds better without his hearing aids. He has done a little bit of experimenting with hopes that he can figure out how to make music sound better.

How Deaf Identity is Expressed

For further information on the components of Deaf identity and how it may affect engagement with music, please see the following page on how Deaf identity is expressed.

Our Statement on Deaf Culture

We on the Music and Hearing Loss team acknowledge Deaf culture and respect its diverse membership, values, and perspectives. Our core contributors are not Deaf. We recognize that it is not our place to speak for Deaf people on their uses of hearing devices and interest or lack of interest in music. We understand that music is not important to everyone. Our aim is to offer a resource for people who would like to enhance their enjoyment and participation in music experiences, including people who are deaf or hard of hearing, their family members, friends, clinicians, and educators.

Resources on Deaf Culture

The following resources offer more in-depth information on Deaf culture, created by and for Deaf individuals:

-

The National Association for the Deaf: https://www.nad.org/resources/

-

Verywell Health: https://www.verywellhealth.com/deaf-culture-4014071

-

Hands and Voices: https://www.handsandvoices.org/articles/articles_index.html

-

The American Society for Deaf Children: www.deafchildren.org

-

Gallaudet University: www.gallaudet.edu

-

Handspeak: https://www.handspeak.com/

-

American Deaf Culture by Thomas Holcolm: http://www.americandeafculture.com/

*There are many different sign languages spoken around the world that help defines the Deaf cultures of different countries. For example, people in France use French sign language. Even though people in England, Australia, and the US all speak English, there is a separate sign language for each of those countries.

References

Adamek, M. S., & Darrow, A. A. (2018). Students with hearing loss. In Adamek, M. S., & Darrow, A. A., Music in special education (3rd ed., pp. 319–358). The American Music Therapy Association Inc.

Darrow, A. A. (2003). The role of music in deaf culture: Implications for music educators. Journal of Research in Music Education, 41(2), 93-110. https://doi.org/10.2307/3345402

Darrow, A. A. (2006). The role of music in deaf culture: Deaf students’ perception of emotion in music. Journal of Music Therapy, 43(1), 2-15. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/43.1.2

Darrow, A. A., & Gfeller, K. (1991). A study of public school music programs mainstreaming hearing impaired students. The Journal of Music Therapy, 28(1), 23-29. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/28.1.23

Darrow, A. A., & Loomis, D. M. (1999). Music and deaf culture: Images from the media and their interpretation by deaf and hearing students. Journal of Music Therapy, 36(2), 88-109. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/36.2.88

Holcomb, T. K. (2013). Introduction to american deaf culture. Thomas K. Holcomb. Oxford.

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.