See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information may be more similar to your situation.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Music Therapy for Older Adults with Hearing Loss:

Considerations for Music Therapy Practice

1, 2

Introduction

Music may not sound 'normal' to individuals with hearing loss who use hearing devices like hearing aids (HAs) or cochlear implants (CIs). This page provides information for music therapists to help understand the impact of a hearing loss on music appreciation and music therapy.

Topics covered on this page include:

Presbycusis

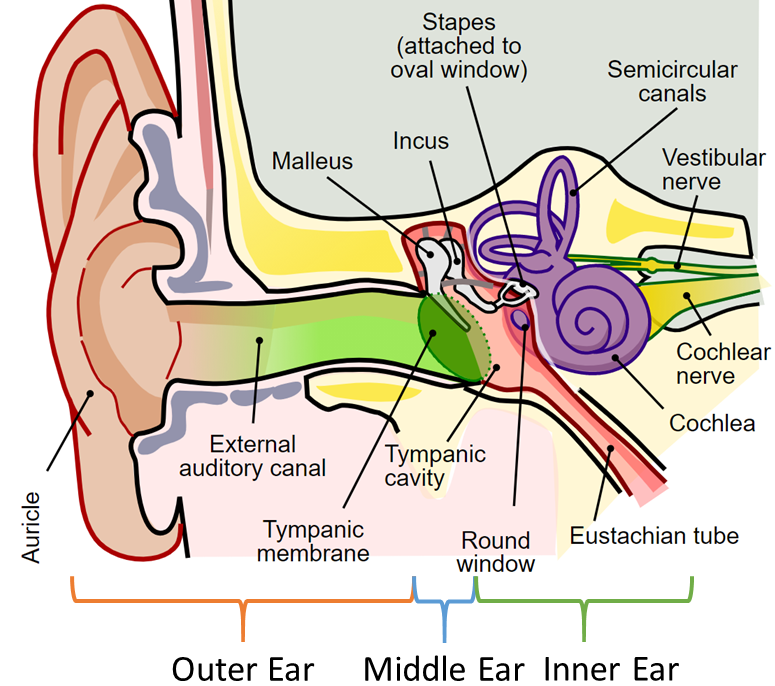

Presbycusis or age-related hearing loss (ARHL) is gradual hearing loss in both ears due to aging; it is common among older adults. As people get older, the hair cells of the cochlea in the inner ear get damaged and gradually die, leading to presbycusis. This is a permanent change because the damaged hair cells do not grow back. Music therapists working with older adults are likely to encounter individuals with hearing loss.

Q. How prevalent is presbycusis in older adults?

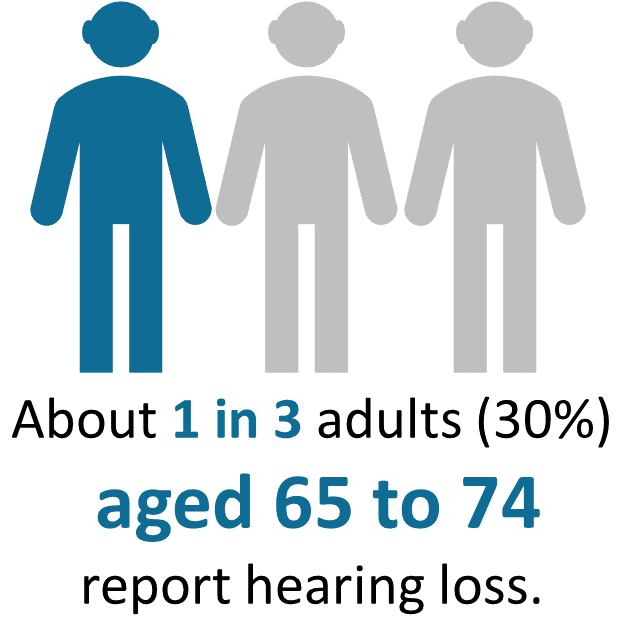

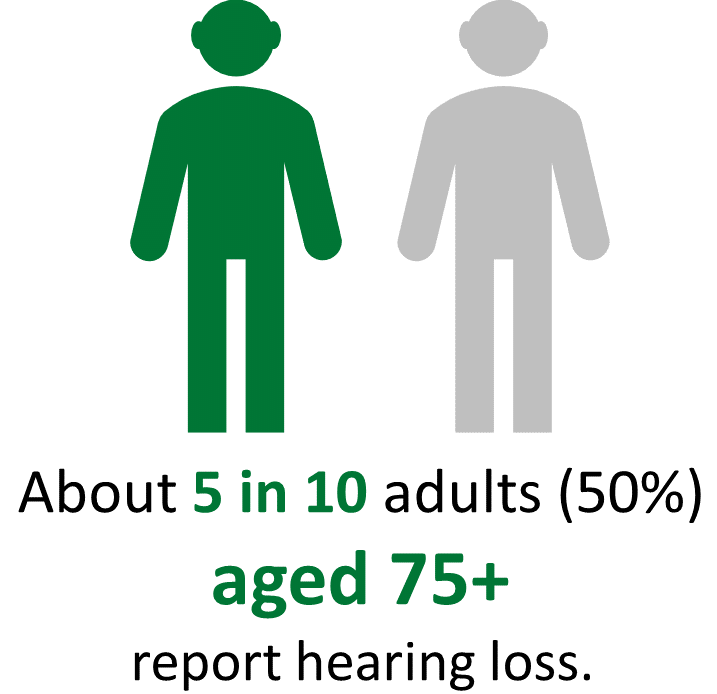

A. The prevalence and degree of presbycusis increase with age, making it more common among older adults.

-

Nearly one-third of adults aged 65-74 and half of those aged 75+ have some degree of hearing loss.

-

Prevalence increases for older adults living in community nursing or assisted living facilities.

-

70-90% are estimated to have hearing loss.

-

(Cohen-Mansfield & Taylor, 2004; U.S. Census Bureau, 2018)

The prevalence of hearing loss with age makes it likely that older adults served by music therapists may have hearing loss and use hearing devices. Therefore, music therapists can learn to provide effective strategies and accommodations for hearing loss to enhance older adults' therapeutic experiences.

Q. What causes presbycusis?

A. There are many causes for presbycusis; most often it occurs due to changes in the following parts of the auditory pathway:

-

Within the inner ear (most common) and along the nerve pathways to the brain (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Anatomy of the Human Ear

Q. What are some symptoms of presbycusis?

A. While each person's symptoms may vary, here are the most common symptoms:

-

Have difficulty hearing conversations in a quiet environment.

- Experience difficulty hearing high-pitched sounds (e.g., women's or children's voices, "s" or "th" sound). The ability to hear low-pitched noises is usually affected to a lesser degree.

-

Have even more trouble understanding conversations in noisy or reverberant places.

-

Background noise may include background music.

-

-

Have trouble understanding conversations over the telephone.

-

Perceive certain sounds such as loud sounds or background sounds as overly loud and annoying.

-

May develop tinnitus (a ringing, buzzing, or hissing sound) in one or both ears.

-

Tend to rely on lip leading.

-

May practice 'social bluffing,' or pretending to hear or understand something that is being said (e.g., nodding, smiling, saying “ok”).

Q. What hearing devices are common among older adults with hearing loss?

A. Hearing devices do not cure hearing loss. They provide greater access to sound.

-

Hearing aids (HAs) are the primary intervention for presbycusis.

-

A hearing aid is an externally worn device that amplifies acoustic sounds through the ear canal to the brain.

-

For more information on hearing aids, click here.

-

-

Cochlear implants (CIs) can be an option for adults with more severe hearing loss who do not obtain significant benefits from hearing aids.

-

A cochlear implant has a surgically implanted electrode array, plus an externally worn sound processor, and a microphone. It is digitally transmitted via electrical stimulation to the auditory nerve. The electrical stimulation is not a replica of musical pitch or timbre.

-

For more information about cochlear implants, click here.

-

Depending on the severity and type of loss, an older adult with presbycusis may be:

-

Unilateral (one HA or CI) user

-

Bilateral (two CIs or HAs) user

-

Bimodal (one HA and one CI) user (most common)

Q. What are some important considerations when music therapy clients have hearing loss?

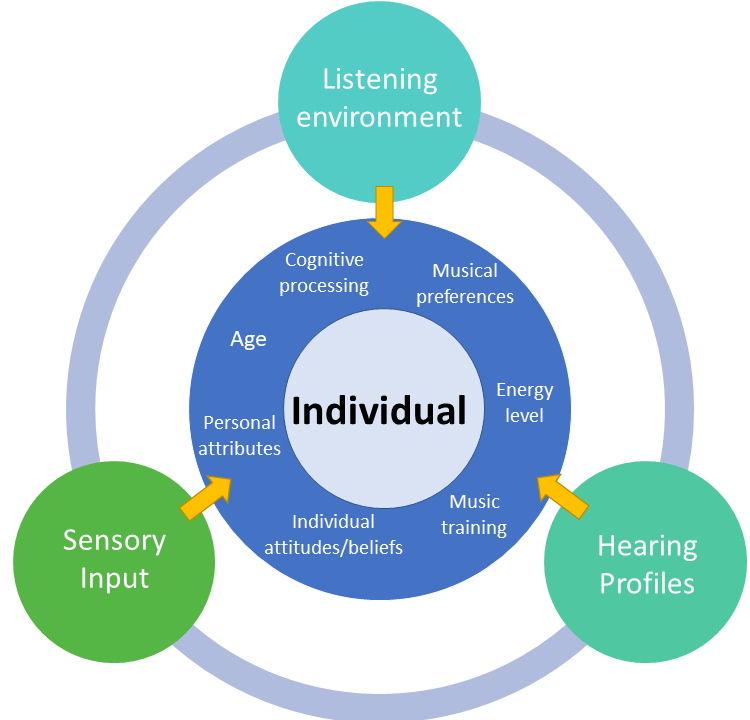

A. Take into account 1) the individual (patients/clients), 2) hearing profiles, 3) sensory input, and 4) listening environment (See figure 2).

Figure 2. Factors that affect music appreciation and therapeutic interactions

-

Individual:

-

People differ in how well they cope with hearing loss.

-

People who normally cope well may have more difficulty if they are tired or frustrated.

-

-

People differ in experiences with music prior to hearing loss.

-

-

Hearing Profiles:

-

People vary greatly in how severe their hearing loss is, and how it affects music AND speech.

-

Most people have some degree of residual hearing or remaining natural hearing.

-

Greater remaining natural hearing (residual hearing) helps with music perception and sound quality.

-

-

Some people who have mild to moderate hearing losses have more residual hearing and get more benefits from wearing HAs.

-

Many persons with hearing loss do not use HAs or do so inconsistently. Research shows the best outcomes from consistent, daily use of hearing devices.

-

-

Some with more severe or profound hearing losses rely on CIs.

-

HAs and CIs do not convey sound the same way.

-

HAs and CIs do not “cure” hearing loss or restore hearing.

-

Most CI users use a hearing aid in the opposite ear; this is called bimodal hearing.

-

-

Sensory Input:

-

Hearing devices convey some parts of music or types of music better than others.

-

Music that has more complex parts tends to be less enjoyable.

-

Music in the background can interfere with spoken communication.

-

For more information about how different musical sounds affect listening enjoyment, click here.

-

-

Listening Environment:

-

Music sounds better in a quiet listening environment than in noise.

-

Music is likely to sound better in a non-reverberant space.

-

-

For more information about how the listening environment impacts music perception, click here.

-

(Gfeller, Darrow, & Wilhelm, 2018)

The table below shows the basic differences between hearing aids and cochlear implants.

Table 1. Comparison of Hearing Aids and Cochlear Implants

|

|

Hearing Aid |

Cochlear Implant |

|---|---|---|

|

Candidates/Population |

|

|

|

Function |

|

|

|

Battery |

|

|

|

Benefits |

|

|

|

Limitations |

|

|

|

Outcome |

|

|

|

Timing |

|

|

(Gfeller et al., 2000; 2010; Leek et al., 2008; Turner et al., 2004; Uys & Van Dijk, 2011; Wilson, 2000)

Q. What does music sound like with hearing assistance?

A. Both HAs and CIs are designed primarily for the transmission of sounds related to speech, not for the sounds of music, although hearing programs for music do exist.

-

Click here to learn more about how signal processing used in HAs plays a role in music perception for HA users.

-

Click here to learn more about the complexities of musical elements with CI technology, on CI and music processing.

The table below shows some differences in music perception in those with HAs and compared to those with CIs.

Table 2. Comparing Music Perception between HA and CI Users

|

|

Hearing Aid |

Cochlear Implant |

|

Overall Music Sound Quality |

|

|

|

Duration (Rhythm, Tempo, Meter, Beat) |

|

|

|

Pitch Elements (Pitch, Melody, Range, Direction, Harmony) |

|

|

|

Timbre (Tone Quality) |

|

|

|

Dynamics |

|

|

|

Lyrics |

|

|

|

Musical Form (Complexity, Texture) |

|

|

|

Instrumentation |

|

|

|

Outcome |

|

|

(Fletcher, 2021; Gfeller et al., 1998; 2001; Gfeller & Lansing, 1991; 1992; Madsen & Moore, 2014; McDermott, 2004)

For me, music is pleasant when I know the song and lyrics and only when one or two instruments are playing. (A CI user).

My CI tends to distort higher pitched instruments and I find that violins, oboe, piccolo and higher pitched instruments very difficult to listen to. (A CI user).

Q. Can older adults with hearing loss still enjoy music?

A. Yes. Despite these difficulties, older adults still report that music is an important part of their lives (Creech et al., 2013). Depending on the degree and type of hearing loss, certain elements of music may still be pleasant (e.g. rhythm), although this varies from person to person. Thus, music can still be a powerful and meaningful therapeutic medium for older adults, including those with hearing loss.

Click the link below for clinical suggestions for optimizing the effectiveness of music and communication during music therapy:

References

Cohen-Mansfield, J., & Taylor, J. W. (2004). Hearing aid use in nursing homes. Part 1: Prevalence rates of hearing impairment and hearing aid use. The Journal of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, 5(5), 283–288.

Gfeller, K., & Lansing, C. R. (1991). Melodic, rhythmic, and timbral perception of adult cochlear implant users. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research, 34(4), 916–920. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshr.3404.916

Gfeller, K., & Lansing, C. (1992). Musical perception of cochlear implant users as measured by the Primary Measures of Music Audiation: an item analysis. Journal of Music Therapy, 29(1), 18-39.

Gfeller, K., Knutson, J. F., Woodworth, G., Witt, S., & DeBus, B. (1998). Timbral recognition and appraisal by adult cochlear implant users and by normal-hearing adults. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 9(1), 1–19.

Gfeller, K., Christ, A., Knutson, J. F., Witt, S., Murray, K.T., & Tyler, R. S. (2000). Musical backgrounds, listening habits, and aesthetic enjoyment of adult cochlear implant recipients. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 11, 390-406.

Gfeller, K., Mehr, M., & Witt, S. (2001). Aural rehabilitation of music perception and enjoyment of adult cochlear implant users. Journal of the Academy for Rehabilitative Audiology, 34(17), 27.

Gfeller, K., Jiang, D., Oleson, J. J., Driscoll, V., & Knutson, J. F. (2010). Temporal stability of music perception and appraisal scores of adult cochlear implant recipients. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 21(01), 028-034.

Gfeller, K. E., Darrow, A. A., & Wilhelm, L. A. (2018). Music therapy for persons with sensory loss. In A. Knight, B. LaGasse, and A. Clair (Eds.), Music therapy: An introduction to the profession (pp.217–245). Silver Spring, MD: American Music Therapy Association.

Hearing Loss Association of America. (n.d.). Hearing Loss Facts and Statistics. https://www.hearingloss.org/wp-content/uploads/HLAA_HearingLoss_Facts_Statistics.pdf?pdf=FactStats

Leek, M. R., Molis, M. R., Kubli, L. R., & Tufts, J. B. (2008). Enjoyment of music by elderly hearing-impaired listeners. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 19(6), 519-526.

Madsen, S. M., & Moore, B. C. (2014). Music and hearing aids. Trends in Hearing, 18, 2331216514558271.

McDermott, H. J. (2004). Music perception with cochlear implants: a review. Trends in amplification, 8(2), 49-82.

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (2021). Quick Statistics About Hearing. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing

U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). Summary health statistics: national health interview survey, 2018. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2018_SHS_Table_A...

Uys, M., & Van Dijk, C. A. (2011). Development of a music perception test for adult hearing-aid users.

Wilson, B. S. (2000). Cochlear implant technology. Cochlear implants: Principles and practices, 109-118.

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.