See also: Articles on Music, Hearing Loss, and Hearing Devices

As you read this website, keep in mind the following:

-

People with hearing loss can differ in many ways.

-

Some information may be more applicable.

-

Pick and choose the information most useful for you.

Using Dynamic Problem-Solving to Manage Music Listening Environments:

Information for Audiologists

1, 2

Introduction

Optimizing music listening requires different considerations than optimizing speech listening. Many factors and approaches for optimizing music listening are similar to auditory rehabilitation for speech communication (auditory profile, expectations, personality, environment). However, CIs technology is much more satisfactory for spoken vs. musical communication [for more information on CIs and music, click here]. Consequently, even though counseling CI users for music perception shares many elements with counseling for speech perception, music enjoyment poses some unique challenges. By addressing these unique challenges, along with patient-specific factors, audiologists can help their CI patients to maximize music enjoyment.

Topics covered in this page include:

Go to this link [Click here] for practical problem solving strategies based upon the Dynamic Problem Solving Model.

The Dynamic Problem Solving Model

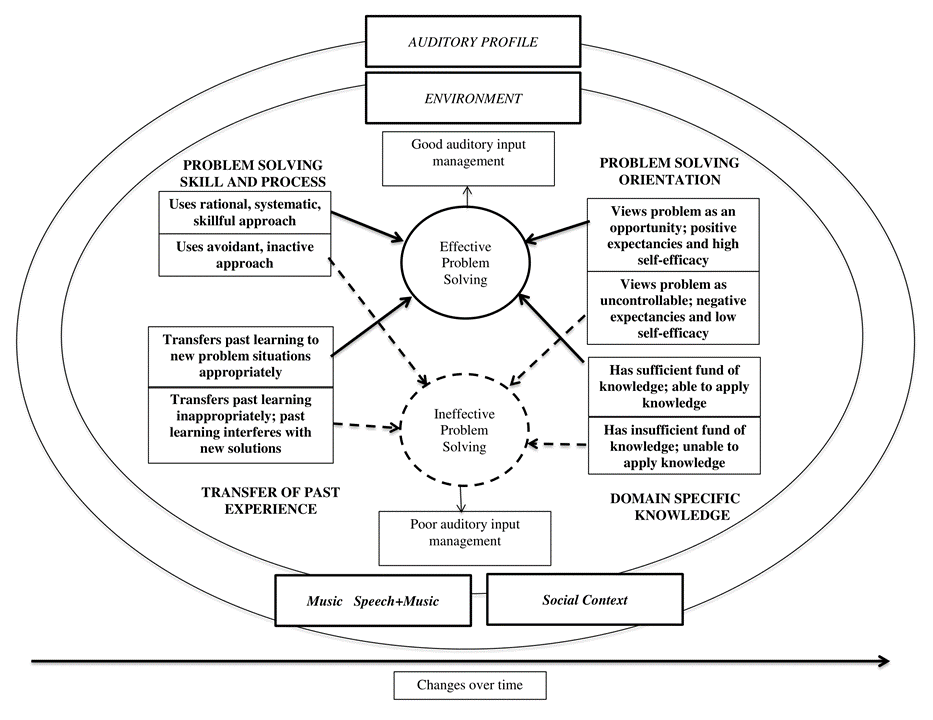

The Dynamic Problem-Solving Model for Management of Music Listening Environments (DPSM-MMLE, see Figure 1), based upon input from CI users, helps to explain the diverse experiences that CI users have with music in everyday life. The model, described in detail in Gfeller, Driscoll, and Schwalje (2019), includes the following components:

-

The auditory profile of the CI user, including any hearing device(s)

-

The listening environment

-

The specific types of musical sounds heard at any given moment

-

Whether music is the listening focus or the background to the conversation

-

The social context in which the music is heard

-

Individual listener differences in problem solving

-

Changes over time with the interaction of these factors

Each of these components is described on this webpage. Keep in mind that these factors interact with one another and change over time. Therefore, satisfactory music listening is a dynamic (changing) process that requires on-going response and adjustment.

Figure 1. Dynamic Problem-Solving Model for Management of Music Listening Environments (DPSM-MMLE) (Gfeller, Driscoll, Schwalje, 2019)

Factors that Affect Music Listening

This section discusses describes the components in the model. As part of counseling a CI user, the audiologist can use this model as a framework for better understanding each patient's experiences, as well as various factors to consider as part of a plan to improve music enjoyment.

Auditory profile:

CI users have different auditory profiles that affect music experiences in different ways.

-

The onset of hearing loss: Expectations about music are affected by the onset of hearing loss.

-

Children who grew up with CIs cannot compare musical sounds filtered through a CI with 'normal' hearing.

-

The lack of comparison can result in reports of more 'satisfactory' experiences of music through a CI.

-

The lack of 'normal' input, especially fine spectral resolution, can affect the development of the auditory system and conceptualization of musical structures.

-

-

Postlingually deaf adults compare music through their CI with musical sounds prior to hearing loss.

-

Comparisons with 'normal' hearing may be very disappointing or frustrating.

-

Some postlingually deaf adults can use their memory of sound through top-down processing (using contextual information) to make sense of the degraded signal.

-

-

-

Age at cochlear implantation:

-

Younger CI users have greater neuroplasticity; they may acclimatize to music through a CI more quickly than adults.

-

Individuals implanted at an older age may need more time and effort to learn how to hear music through their CI.

-

-

Health of the auditory pathways:

-

Residual hearing? Greater residual (acoustic) hearing helps CI users to process spectrally complex components of music.

-

Residual hearing improves the perception of pitch/melody/harmony and timbre/tone quality.

-

-

Length of auditory deprivation: More extensive deafness undermines the health of the auditory pathways and thus reduces the benefits of the device.

-

-

Type of hearing device used and individual benefit:

-

Electrical vs. acoustic hearing? Electrical stimulation conveys a degraded representation of pitch and timbre.

-

CIs that preserve remaining residual hearing are more likely to result in better musical sound quality.

-

Bimodal hearing: Some CI users with sufficient residual hearing report that the use of hearing aids along with CIs improves music enjoyment.

-

Device benefit: CI users vary in how much they benefit from the cochlear implant's internal array and signal processor.

-

This variability is not fully understood. Some differences may include:

-

The fit of electrodes in relation to a normal tonotopic organization in the cochlea.

-

How many electrodes are viable.

-

The extent of current spread among electrodes.

-

The extent of fine spectral information in the signal, in conjunction with the condition of the auditory pathway.

-

Successful use of special settings on the CI or assistive listening devices (e.g., external microphones).

-

The responsiveness of the auditory system to stimulation.

-

-

-

-

The audiologist can take into account the auditory profile when counseling CI users about realistic expectations and suitable rehabilitation options. For example, postlingually deaf adults may expect music to sound as it did when they had normal hearing. Managing expectations is a critical part of the counseling and rehabilitation process.

The audiologist can point out different auditory characteristics that help explain why musical experiences differ from one user to the next. The audiologist can also consider the auditory profile when considering the most effective options to optimize music enjoyment (e.g., use of contextual cues? mental representation of musical sounds).

The listening environment:

-

Room acoustics: Rooms with a lot of hard surfaces and reverberation (echo) tend to make music harder to understand.

-

Competing noise in the room: Competing conversations or noise (air handling systems, etc.) makes listening to music more difficult.

-

Poor lighting: Rooms with dim lights or background glare can undermine access to visual cues that can support music perception.

-

Sound system: Poor quality or loud sound systems can be uncomfortable, distort musical sounds, and mask softer sounds.

Taking steps when possible to select or modify the listening environment can make listening less difficult and tiring. An audiologist can increase the CI user's awareness of these factors and recommend helpful strategies.

The music being heard, and whether speech is also involved:

-

All music is not alike: Music varies in style (e.g., country, classical, pop) and structural components (rhythm, melody, harmony, timbre).

[Click here to view the page on music and cochlear implant technology]

-

More complex music is harder to understand.

-

Fewer instruments or singers making music at once tend to be easier to understand.

-

For example, orchestral music has many instruments and complex melodies and harmonies. That may be more difficult to enjoy compared with pop or country music, which is often played by fewer musicians and with simpler musical elements.

-

-

-

Music that emphasizes rhythm will be easier to understand than music that emphasizes melodies.

-

Music familiar from before the hearing loss may be easier to understand through top-down processing (e.g., using contextual information to make sense of sound)

-

Background music that competes with speech can make speech harder to understand.

-

Talkers in the background of music, such as at a concert, can make the music harder to understand and enjoy.

Proactive CI users can experiment with different music selections to find types that are most enjoyable. Ask your patients what music they enjoy. Consider playing their favorite music during programming sessions and discuss their perceptions and experiences.

The social context in which the music is heard:

-

Music often occurs in social settings:

-

How many people are there in the listening environment? Are they talking or listening quietly to the music?

-

Do conversation partners understand the challenges associated with CIs, and support accommodations?

-

Seeking out less noisy listening environments and informing conversation partners about communication needs can improve listening.

Individual differences in problem solving and psychological characteristics:

-

Expectations: CI users differ in their opinions and expectations about listening to music through their device(s).

-

Someone who got a CI later in life and is used to hearing music naturally may be disappointed because music does not sound the same as it did before.

-

Someone who has not heard music 'naturally' at all has no existing expectations and may enjoy the sound.

-

Someone with realistic expectations may be better able to appreciate incremental improvements in music listening, or find situations or types of music that are more satisfactory than others.

-

Expectations may change over time as the CI user adjusts to their hearing status and CI use. Click here to see information on stages of adjustment to hearing loss.

-

Talk with your patients about realistic expectations pre- and post-implantation. Provide information on accommodations and rehabilitation.

-

Domain-specific knowledge: CI users vary in how much they know about CI technology and limitations associated with complex listening experiences, such as music. Domain-specific knowledge forms the foundation for dynamic problem solving, self-efficacy, and self-advocacy.

-

Audiologists can support CI users by providing easily understood handouts or links to quality websites.

-

Audiologists have many tests, device maintenance, and counseling to address in regular appointments. Therefore, save time by preparing a list of resources to share with CI users for whom music is important. This website has webpages designed specifically for CI users.

-

-

CI support groups can share domain-specific knowledge, strategies, and encouragement.

-

-

Effective transfer of prior knowledge to new tasks: Successful problem solving means the suitable application of prior knowledge to new situations.

-

The audiologist may need to point out differences between hearing aid use and CIs with regard to music enjoyment.

-

For some users, music will sound worse through a CI than a hearing aid, due to the spectral resolution limitations of CIs.

-

For some users, the improved audibility provided by the CI will make music listening more enjoyable than it was with a hearing aid

-

-

-

Problem-solving skills and processes: Successful problem solving requires logical and systematic approaches to taking on challenges.

-

Encourage the CI user to keep a log/diary of strategies and situations that are most successful.

-

Provide a checklist of strategies that can be used in different circumstances.

-

Encourage the development of a plan or schedule for practicing music listening. Short but more frequent practice tends to be more effective than massed practice.

-

Talk to the CI user through the real-life scenario at the links below which illustrate problem-solving processes.

-

Click here to access information about optimizing music listening of CI users

-

Click here to learn about problem-solving strategies when going to a restaurant

-

Click here to learn about problem-solving strategies when going to a concert

-

Click here to learn about problem-solving strategies when listening to music at home

-

-

-

Problem-solving orientation: Confidence in one's problem-solving ability is sometimes described as self-efficacy. Self-efficacy can vary, however, from one domain to the next (e.g. at work, at home, in social situations). For more information on self-efficacy, Click here.

-

People with a strong problem-solving orientation are more likely to consider problems as interesting challenges; they are more confident about achieving positive results.

-

They actively seek information about challenges and possible solutions, including attending support groups or enrolling in training.

-

They use information and resources about hearing loss, hearing devices, and music as a foundation for problem solving.

-

They are more likely to persevere despite incremental improvement or frustrations.

-

-

People with a low problem-solving orientation see problems as uncontrollable barriers that they are unlikely to overcome. The dynamic nature of problem solving may seem overwhelming to some CI users who would prefer more 'cut-and-dried' solutions to complex listening situations.

-

Audiologists should consider the individual's readiness to problem solve vs. desire for more structured advice.

-

-

-

Psychological Characteristics:

-

The brain's interpretation of electrical or acoustic plus electric stimulation will be influenced by the individual's cognitive processing patterns; these are influenced by genetics, physiology, and life experiences (including training).

-

Some people have neurological characteristics that process and make sense of patterns of sound more quickly.

-

Personality characteristics, sometimes known as "The Big 5" (Costa & McCrae, 1992), can affect how people approach challenging circumstances. This includes listening to music, following through on guidance from health professionals, and receiving input and support from family and friends. The Big 5 traits include openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, and extraversion.

-

Openness: Inventive and curious vs. consistent and cautious.

-

Inventive and curious people are more likely to experiment with music listening to see what works.

-

Difficult situations are viewed as challenges and opportunities for learning new skills.

-

Individuals who have high levels of openness may be interested in training programs to optimize perceptual efficiency.

-

Individuals who lack openness may resist changes in routines or trying alternative approaches.

-

-

Conscientiousness: Efficient and organized vs. extravagant and careless.

-

Conscientious individuals tend to be more consistent in maintaining their device(s) and in following guidance from their audiologist.

-

Conscientious individuals will be more likely to follow through on recommendations for improving listening.

-

-

Agreeableness: Friendly, cooperative, and compassionate vs. challenging and callous.

-

A desire to interact effectively and empathically can motivate listening effort.

-

Individuals who are not agreeable may resist input from clinicians and family.

-

-

Neuroticism: Sensitive and nervous vs. resilient and confident.

-

People with greater resilience and confidence are more likely to bounce back and persist in the face of frustrations or failed attempts.

-

Resilience is important because improved music enjoyment typically requires perseverance and trial and error.

-

Resilience can be encouraged through modeling and positive reinforcement.

-

-

-

Extraversion: Outgoing and energetic vs. solitary and reserved.

-

An extroverted person is more likely to socialize regularly. The desire to communicate effectively with others can motivate listening effort and practice.

-

-

-

-

-

The personal importance of music influences motivation to optimize listening experiences.

-

Music varies in importance to different individuals, families, and cultures.

-

Musical taste varies among listeners; thus, a selection of meaningful music is important to motivation.

-

-

Some individuals attach greater importance to music as part of their personal identity.

-

Audiologists should directly ask their CI patient about the importance of music in their life and proceed accordingly; not all patients will bring it up unprompted because appointments are short and can be overwhelming.

-

-

Audiologists should take into account orientation toward problem solving, individual psychological characteristics of their patients, and inquire about the importance of music to each patient and the patient's musical preferences and habits as part of patient intake.

Changes over time: These factors can change from minute to minute or over weeks/months/years.

-

The auditory profile of the CI users: Residual hearing or benefit from hearing devices can change over time.

-

Hearing health may continue to deteriorate over time.

-

CI users can acclimatize and become more adept at using the speech signal with extended use.

-

Focused practice or training can improve music enjoyment over time.

-

Helping the CI user to persist in the face of incremental improvement or difficulties is important.

-

-

-

The listening environment: Competing noise or lighting can change over time.

-

The musical sounds being heard: Melodies, harmonies, timbre, rhythm, and dynamics continually change. Some parts of music may be easier to understand than others.

-

Music as the listening focus vs. background to a conversation: In situations like a bar/jazz club or a religious service, music may shift back and forth from the primary focus to ambient music. Many CI users find this shift among the most difficult music experiences to negotiate.

-

The social context in which the music is heard:

-

The number of people creating background noise can change.

-

Some people are more supportive of listening needs than others.

-

-

Individual differences in problem solving:

-

The ability to solve problems and self-advocate will change depending upon:

-

The specific circumstances (including how much control the listener has over the situation).

-

How flexible and oriented toward problem solving the listener is.

-

How alert and well-rested the listener is.

-

How much quality information about hearing loss, CIs, and music is available.

-

Prior training/mentoring/experience in problem solving.

-

Personal attitude regarding challenging situations.

-

Support from family, friends, hearing professionals, and other advocates.

-

Attitude toward one's hearing loss, and readiness for change [click here to view information on readiness for change].

-

-

These changes over time require a dynamic approach to assessing and counseling patients with regard to music listening and participation. Audiologists can help CI users to realize the dynamic nature of listening and the need for ongoing response to circumstances. For more information on counseling CI users, visit Optimizing Music Listening of Cochlear Implant (CI) Users: Information for Audiologists.

These links take you to Decision Trees, which illustrate step-by-step problem solving for several complex listening environments:

Suggested readings:

This article discusses various factors that contribute to pleasant or difficult music listening experiences with a wide range of adult CI users.

-

Click on the title to access the article: Gfeller, K., Driscoll, V., & Schwalje, A. (2019). Adult Cochlear Implant recipients’ perspectives on experiences with music in everyday life: a multifaceted and dynamic phenomenon. Front. Neurosci., 13, 1-19

This article shares input from a unique cohort of CI users who are high-level musicians, and their strategies for improving music enjoyment and music-making.

-

Click on the title to access the article: Gfeller, K., Mallalieu, R. M., Mansouri, AL., McCormick, G., O’Connell, R. B., Spinowitz, J., & Turner, B. G. (2019). Practices and attitudes that enhance music engagement of adult cochlear implant users. Front. Neurosci, 13, 1-11

Click here to review references used in preparation of this website.

1. All images on this website are used under Creative Commons or other licenses or have been created by the website developers.

2. Click here to access the sources of images on this page.